Projected global warming under current global emissions reduction policies will leave many of our region’s human and natural systems at very high risk, and will put some beyond adaptation.

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, released on 28 February, follows last year’s report that focused on the physical science of climate change, and further emphasises the need for immediate action on global emissions.

It comprises 18 chapters representing the efforts of more than 200 scientists in reviewing the latest information about how climate change is affecting natural and human systems, future risks, approaches to adaptation, and links to climate-resilient development.

Chapter 11 of the report, of which I was a lead author, explains that exposure to climate trends and extreme events of many natural systems and some human systems, combined with their existing vulnerabilities, have already resulted in major impacts in Australia.

Extreme events such as heatwaves, droughts, floods, storms and bushfires have caused deaths and injuries, and affected many households, communities and businesses at considerable economic cost.

It’s some of our iconic ecosystems that are at greatest risk from current and future climate change.

The greatest risk is for the loss and degradation of coral reefs and associated biodiversity and ecosystem service values in Australia due to ocean warming and marine heatwaves.

The three marine heatwaves that occurred between 2016 and 2020 have caused significant bleaching and subsequent loss of corals and associated marine life, and an increased frequency of such events under climate change will exceed the reef’s regenerative capacity.

Other key regional risks identified include:

- the loss of alpine biodiversity in Australia due to less snow

- the transition or collapse of alpine ash, snow gum woodland, pencil pine and northern jarrah forests in southern Australia due to hotter and drier conditions with more fires

- the further loss of underwater kelp forests in southern Australia that is driven by ocean warming and marine heatwaves

- the loss of natural and human systems in low-lying coastal areas due to sea-level rise

- the disruption in agricultural production and increased stress in rural communities in southern and eastern Australia due to hotter and drier conditions

- an increase in heat-related mortality and morbidity for people and wildlife due to heatwaves.

We also identified two emerging kinds of climate risk.

One is the cascading and compounding impacts on cities, settlements, infrastructure, supply chains and services, due to events such as bushfires and heatwaves.

A good example is the Black Summer fires of 2019-2020 that took many lives directly, but also produced extreme air pollution that affected agricultural production, human health and tourism.

The other is the inability of institutions and governance systems to manage climate risks because the scale and scope of projected climate impacts may overwhelm the capacity of institutions, organisations and systems to provide necessary policies, services, resources and coordination to address the socio-economic impacts.

The issues of adaptation, especially to heat in Australian cities, is of particular interest, but it’s not all bad news. Compared to the last IPCC assessment, the adaptation process has improved across governments, non-government organisations, businesses and communities in Australia.

In Australian cities, local governments are making impressive efforts to adapt to climate change and its impacts. Urban forests and irrigated vegetation are very good at reducing heat impacts, especially during heatwaves, and many local government areas have established targets for tree cover and integrated water management that can support healthy transpiring vegetation and reduce temperature.

However, the reality is that even with further improvements in the adaptation process, our ability to adapt our way out of trouble will be severely compromised without rapid decarbonisation to limit warming.

The key point for governments to note is that there are clear limits to adaptation, and that we’re rapidly approaching those limits, so action on emissions is critical and must urgently be enacted.

This article was originally published on Monash Lens. It is republished under Creative Commons.

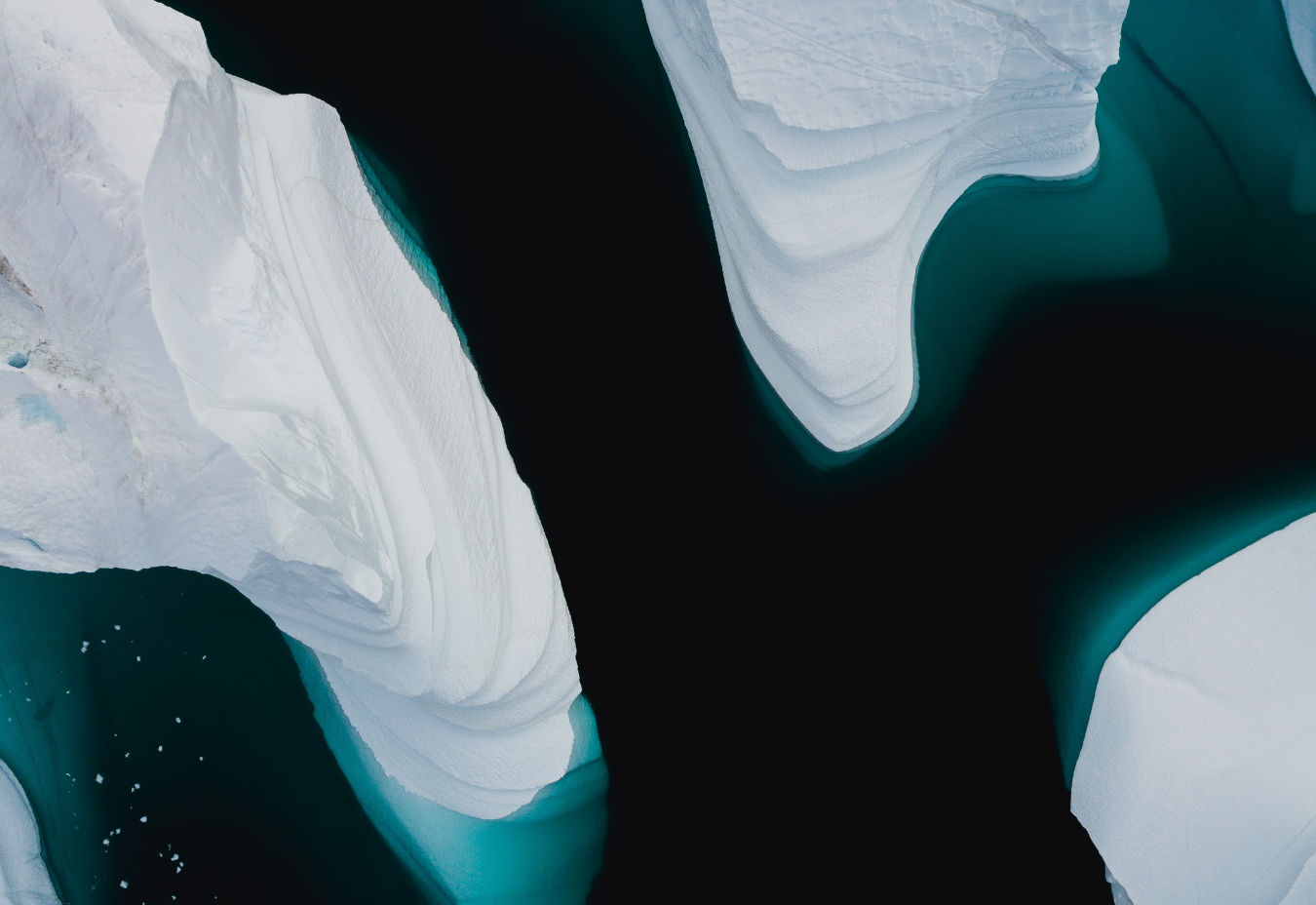

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash.