The day that Vladimir Putin sent Russian forces into Ukraine, President Biden spoke publicly about the sheer mendacity of Putin’s propaganda and the total lack of justification for his invasion of Ukraine.

He then announced severe financial and trade sanctions on Russia, designed to punish Russian aggression and pressure Putin to reconsider his strategy. There had been widespread scepticism that financial sanctions could substitute for the use of countervailing force. But these sanctions will bite. And Putin may well have bitten off more than he can chew.

Speaking on television a matter of days before Russian forces crossed Ukraine’s borders en masse and Russian missiles and bombs began to rain down on Ukrainian cities, I expressed the opinion that Putin surely had limited aims and would proceed cautiously to annex slices of Ukrainian territory in which there were large numbers of ethnic Russians, but would not launch an all out offensive. I was in error. I gave him too much credit for canniness and strategic good sense. He has gone in deep and hard. He may now find it very difficult to stabilise his position or regain credibility. This war could bring him down.

While Putin has put Russia’s nuclear forces on high alert, the West is not sending in NATO military forces. Instead, as President Biden has made clear, it is acting as a massive economic and geopolitical coalition to impose crippling costs on Russia for its assault on a neighbouring state. As CNN reported:

A number of Russian banks will soon be expelled from the SWIFT global messaging network, in many ways the backbone of global commerce. Even more significant is the commitment to target Russia’s central bank with sanctions that sever its ability to conduct transactions with Western banks.

The move would undo years of work by Russian President Vladimir Putin to sanction-proof his economy by amassing a $630 billion war chest of foreign currency reserves. If Russia’s central bank is barred from selling those reserves through foreign banks, that stockpile would essentially be rendered useless.

Russia’s economy, already grappling with its stock market’s worst week on record, an all-time low for its currency against the dollar and soaring borrowing costs, now faces a true crisis moment.

These measures are ground-breaking. They put non-violent pressure on Putin to an extent that he does not seem to have thought possible and they will, at least potentially, cripple his capacity to sustain his war. What he does as they bite will be very interesting to watch.

Outside a few specialist circles, however, even within émigré communities, there is little reliable knowledge of the history behind the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, both in the decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union (which included both), in 1991, in the 20th century, when the Communist Party ruled both and in the thousand years before that, when the shape and sovereignty of both changed a good deal.

This column is simply a brief essay in putting those things into depth of perspective. It isn’t an up to the minute bulletin on the fortunes of war. Everyone can find news reports in countless sources. It’s a reflection on what lies behind the conflict and how it might reshape the geopolitics of Europe and Eurasia.

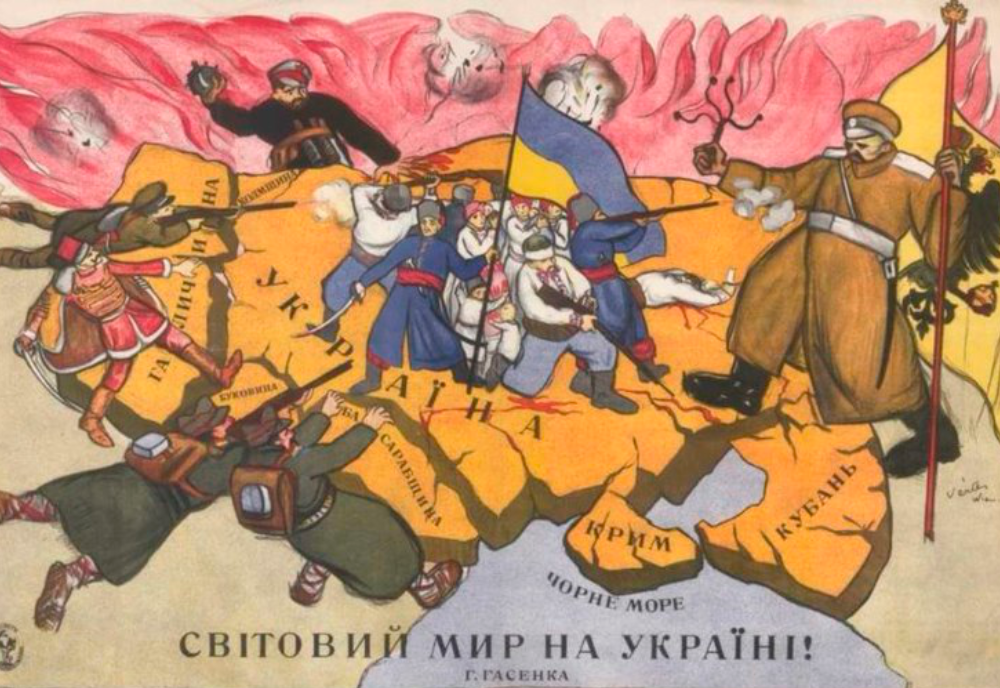

For those seeking a good introduction to the history of Ukraine, there is no better source book than Serhii Plokhy’s The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine (Penguin, 2015). The first thing it makes clear is the extent to which the borders of various states in Eastern Europe and what are now Russia, Ukraine and the Baltic states have changed over the past millennium and more. This is not, of course, something peculiar to that part of the world. But it is a very useful corrective to assertions from Moscow that Russians and Ukrainians are ‘one people’ – who should by rights be ruled by a despot in Moscow.

A thousand years ago, stretching from the Finnish lakes to the Black Sea and from the Vistula to the Volga, there was a state called Kyivan Rus, with its capital in Kyiv/Kiev. Alongside Kyivan Rus, between the ninth and 15th centuries, there were a number of other Slavic, Varangian and Khazar states in what are now Russia, Ukraine and the Baltic states. The principality of Muscovy (Moscow) did not arise, as such, until the second half of the 13th century and, even then, it was a vassal state of the Mongols.

Over the following two hundred years, the Duchy of Muscovy imposed itself on a number of other cities, notably Novgorod (1478) and Tver (1485), even as it fought to shake off the dominance of the Mongols. During that same period, Kyivan Rus had been replaced, over much the same territory, by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Duke Ivan III of Muscovy, during his 43-year reign (1462-1505), fought a series of wars against the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, tripled the territory of Muscovy, adopted the title ‘Tsar’ (Caesar) and declared himself, in his final years to be the ruler of all ‘Rus’. Putin’s claims, in short, date back not to the Soviet Union but to the first Russian Tsar, Ivan III. But those in the old Kyivan and Lithuanian lands have a different view of the matter.

Putin’s claims, in short, date back not to the Soviet Union but to the first Russian Tsar, Ivan III. But those in the old Kyivan and Lithuanian lands have a different view of the matter.

Why did Ivan III style himself ‘Tsar/Caesar’? Constantinople had fallen to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, before Ivan became Duke of Muscovy. He married Sophia Palaeologa, a niece of the last Byzantine Emperor, Constantine XI Palaeologus, and, on that basis, declared Muscovy to be the successor state of the Roman Empire, the ‘Third Rome’. Even so, it was centuries before the western borderlands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and its successor state the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were absorbed into the expanding Russian Empire. It was the Union of Lublin, in 1569, that created that Commonwealth, separating Ukraine from Belarus and deepening the Kyivan identity of Ukraine. There were internal divisions within the Commonwealth, but the main external threat to it was from the Duchy of Muscovy.

The new Tsardom of Muscovy and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were, from the 15th century onwards, locked in a prolonged struggle for control of Ukraine. Tsar Ivan the Terrible (1530-84), the Vladimir Putin of his day, fought relentlessly to impose Russian rule on what are now Kazakhstan, the Baltic states (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia), Belarus and Ukraine. He failed in this endeavour, lapsed into paranoia after a violent purge of his own state council and his death was followed by the so-called Time of Troubles, in which the very future of the Russian state was in doubt. NATO’s resistance to Putin, in fact, bears striking similarities to the resistance Ivan the Terrible faced from the Swedes, Poles, Lithuanians and Ukrainians long ago.

The Romanovs came to power in 1613 and, over the following three hundred years, gradually asserted their rule over Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, Estonia and Finland. It was only between 1772 and 1795, however, that the three partitions of the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania imposed Russian rule on Ukraine as a whole, along with parts of Poland and all of Lithuania. That control would last until the Russian Revolution of February 1917, when the Russian Empire disintegrated. The Soviet Union, however, set about reconsolidating much of that Empire and maintained its dominance until it, too, disintegrated in 1989-91. Putin’s geopolitics are a reaction to that second disintegration of Russian power.

The questions that are in play in 2022 are: the capacity of Putin’s Russia to reassert imperial sway by force, in the tradition of Ivan the Terrible and the Romanovs, Lenin and Stalin; the possible fall of Putin in the event his imperialism does not succeed in Ukraine; and the scope for drawing a chastened and democratising Russia, at last, into the Western and European order of states – as Mikhail Gorbachev had hoped in the late 1980s. To think this set of questions through is the strategic task of Western leaders and Russian elites and dissidents right now, even as Putin’s forces rage in Ukraine.

The fact that severe sanctions have been imposed by a more or less cohesive US-led coalition of states, rather than a military intervention in Ukraine itself being mounted by NATO, should not be seen as a sign of weakness or irresolution. Rather, it should be heralded as the harbinger of a better order and of less destructive means for bringing aggressors to heel.

In 1991, the Soviet Union disintegrated and the subsequent attempt to marketise and democratise Russia failed rather badly. There is the possibility now that a much better transition can be brought about.

China, meanwhile, will be watching how all this plays out. Under Xi Jinping, more than ever, the Communist Party is allowing Han chauvinism and imperial aspirations to override good sense and internationalism. It is rewriting history to lay claim to Mongolia, as well as Xinjiang, Tibet and Taiwan, rather than seeking to draw them, as neighbouring states, into a secure and non-imperial commonwealth or economic confederation.

There is no antagonism, in Ukraine or the Baltic states or Poland or Finland, towards Russia as such, or even towards trade with Russia. There is fear of Putin and his kleptocratic regime – likewise, as between China and its neighbours. All this is at stake in Putin’s brutal and wholly unjustified war. Whatever reasonable ethnic, territorial or economic aspirations either Russia or China have, within their immediate peripheries, can be negotiated. The use of force to dominate those peripheries, however, challenges world order and must be opposed – preferably without wider war. The sanctions on Russia meet that description.

Photo by Samuel Jeronimo on Unsplash

I usually enjoy Paul Monk’s articles, both in the RSA and elsewhere, finding them thoughtful and knowledgeable, indeed erudite. This however is a disappointing exception. It’s tendentious and highly disingenuous, not so much for what it says but what it omits.

He take us on a tour of Ukrainian history, beginning 1,000 years ago and ending in… wait for it, 1992. (I.e. the breakup of the Soviet Union.)

Fast-forward to now, and he writes “Putin’s geopolitics are a reaction to that second disintegration of Russian power.”

This ignores the intervening period, in which quite a bit happened that might be though germane to the discussion. In particular, the agreement between Bush and Gorbachev that in return for the latter’s acquiescence to the re-unification of Germany, NATO would not expand eastwards. “Not one inch” said James Baker, Secretary of State at the time. On which they promptly reneged, to the point where now Ukraine remains the only buffer between Russia and NATO countries, and it’s agitating to join.

Consider: would the USA tolerate for one moment the presence of Russian troops and missiles in, say, Mexico? Or Cuba? We know the answer to that.

Then there were the 2015 Minsk Accords, about which I know little except that they were meant to be a path to some kind of autonomy for some of the Eastern Ukrainian states, perhaps like Quebec in Canada; there are many such regions in the world. Ukraine reneged on those.

The Eastern provinces are, by any practical criteria, Russian. They speak Russian, people there have family on the other side of the border. They’ve been fighting a war of succession for a decade; 14,000+ people have died. They will welcome the Russians.

And let’s not forget the West’s bombing of Serbia (a sovereign country) in support of the breakaway province of Kosovo. (An action by which Russia was humiliated.) A righteous war perhaps, but no different in principle to Russia’s military support of Donetsk and Luhansk.

To widen the lens a bit, the USA ever since WWII has had no qualms about military intervention in any number of (sovereign) countries in what it considers its backyard (and quite a few much further away), in the cause of suppressing “Communist insurrection” or whatever.

There’s a heavy stench of hypocrisy in the air.

To be clear, I am not a supporter of Putin, he’s a thug and a vicious despot. Nor am I for one moment supporting the invasion, or suggesting that the West should not be reacting as it is in terms of condemnation and sanctions.

What I do think is that anyone who considers themselves a Rationalist should be wary of the jingoistic stuff we’re being swamped with, and take a more nuanced view of events.

Russia has a valid case, and it should be conceded rather than ignored. I say “Russia” rather than “Putin” because this is a geopolitical play (as Paul said), and to ignore that simply vilify him is just propaganda, and there’s a lot of that about at the moment.

(Some of it’s quite subtle, in the way things are framed. E.g. the constant phrasing “Russia has invaded its neighbor”. Objectively true, but a more neutral way of putting it would be “Russia has invaded neighboring Ukraine”. The latter just indicates immediate proximity, whereas the former plays on all kinds of deep-seated emotions about how one should relate to one’s neighbor, going right back to the Biblical commandment that a man should not covet his neighbor’s wife, nor his ass. Nor presumably his deep-water ports 🙂 )

For anyone who’d like to get some alternative views to those in the mainstream media, you could do a lot worse than Guy Rundle in Crikey, or John Menadue’s Pearls and Irritations website.

– Russell Cameron, 2/3/2022

Is the new (Ras)Putin another mad monk or another Czar?