This article is part of our ‘A secular Australian future’ feature series to mark the first Secularism Australia Conference, being held on Saturday 2 December in Sydney.

Last year, when the newly appointed President of the Senate, Sue Lines, publicly expressed her support for removing the daily recital of Christian prayers from the Senate’s procedures and her job description, her Labor colleagues swiftly pulled her back into line.

Now, whenever the Senate opens for the day, we can all watch on – see the livestream here on the Australian Parliament House website – as an atheist is forced to recite two Christian prayers, including the Lord’s Prayer, for the Senators and staff in attendance before everyone can get on with their jobs.

Senator Lines is clearly uncomfortable reading prayers aloud. There is little enthusiasm in her voice as she calls on “Almighty God” and pledges that the Senate will “humbly beseech Thee to vouchsafe Thy special blessing”, and work as “Thy servants to the advancement of Thy glory”.

Forcing a non-religious person – indeed, the presiding officer – to partake in acts of religious worship against her will diminishes the Senate as an institution. Furthermore, it is contemptuous of our nation’s diverse community.

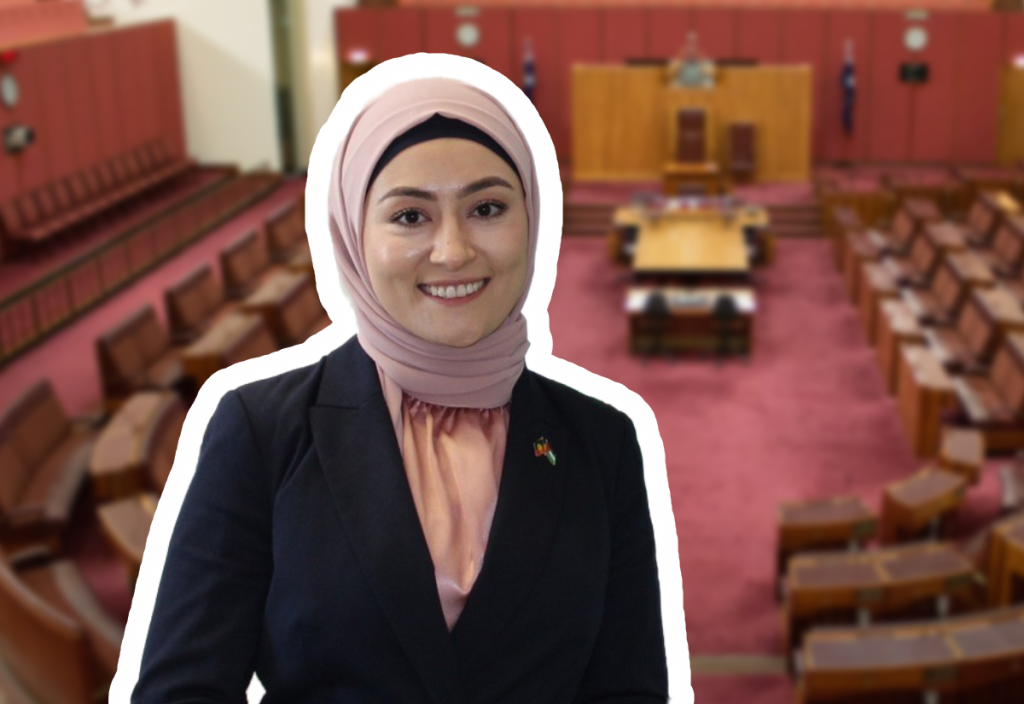

So swift was the response by Labor leaders including Penny Wong and Don Farrell to President Lines’ public utterances about the need for change that the debate was dead on arrival. When the Senate officially opened for the new term, President Lines duly recited the Christian prayers. Among the new Senators forced to observe them was Labor’s Fatima Payman, a hijab-wearing Muslim from Western Australia.

Wong and Farrell had argued, according to The Australian, that any changes to the practice “should aim to unite senators rather than divide”. Apparently, the Labor Party thought it would be “uniting” to continue imposing acts of religious worship in one particular religion in what should be a secular institution.

And this was from Wong, who, in 2017 argued, in a keynote speech to the annual Frank Walker Lecture, that the separation of church and state was necessary to ensure equal rights. In the speech, she said:

“Religious freedom means being free to worship and to follow your faith without suffering persecution or discrimination for your beliefs. It does not mean imposing your beliefs on everyone else.”

Senator Lines was certainly not the first member of an Australian parliament to publicly take a stand against the recital of prayers as part of formal business. Many have gone before her; yet, clearly, none of the many parties have listened to these pleas or cared.

In her 2001 book For God and Country, academic Marion Maddox shows how the idea of including prayer recitals as part of the formal proceedings of the new national parliament after Federation was, even then, controversial.

In one example given, King O’Malley, the American-born politician who served in the House of Representatives, questioned how his colleagues would retain their “deep-seated reverence for prayer” if they were forced to listen to a Speaker who had been on the “spree” the night before. O’Malley thought it should be the MPs praying for the Speaker instead!

Maddox notes that, in arguing against including prayers as part of formal parliamentary business, some MPs framed their concerns in terms of their own religious convictions. Prime Minister Edmund Barton suggested that MPs should take the advice of “a very high teacher” and “pray in our closet”. A South Australian senator, Gregor McGregor, said he was in favour of “the religion that is in the heart” and against that “on the coat-sleeve”.

The fear that prayers may have to be recited by a non-Christian was never too far away. McGregor worried that Senators may have to “sit here and listen to somebody committing what to my knowledge may be an act of blasphemy”. But others, including Western Australian Senator George Pearce, believed no harm would be done even if atheists were charged with uttering the prayers.

Unsurprisingly, some religionists still think that prayers are a good thing for everyone to partake in. In the Senate last year, Tasmanian Liberal Jonathon Duniam, a Christian, suggested that observing prayers “wouldn’t be a bad thing” even for atheists.

In recent decades, there have been other presiding officers of the Senate and the House of Representatives – Presidents and Speakers, respectively – who have questioned the appropriateness of reciting Christian prayers. Maddox notes that, in 1996, the retiring President of the Senate, Michael Beahan, called for reform of the practice, saying:

“I believe the Prayers in our standing orders are an archaic and anachronistic form of words that really should be changed.”

In the Australian Book of Atheism (2010), Ian Hunter – a Labor member of the South Australian Parliament – noted that, in 2008, Speaker Harry Jenkins called for public debate on the relevance of prayers in parliament. An atheist, Hunter was himself outed by Adelaide’s Advertiser newspaper in 2007 for using the prayer time “to catch up on some reading”.

Hunter still sits in the Legislative Council and, according to a source of mine, can sometimes be seen reading science magazines during the daily prayer.

In the 1980s, then President of the South Australian upper house Anne Levy, an atheist, sought to delegate the reading of the prayer to someone else. But, as Hunter notes, she was barred from doing so.

In recent decades, a number of MPs in the federal parliament and across the states – including the likes of Lyn Allison, Bob Brown, Lee Rhiannon, Mehreen Faruqi, Tim Watts and Clare O’Neill in the federal parliament, and Fiona Patten, Mike Gaffney, Robert Simms, Abigail Boyd, Brian Walker and Sophia Moermond across the states – have called for prayers to be replaced with more appropriate practices.

There is hope on the horizon that our democratic institutions will finally begin to reflect the religious and non-religious diversity of the Australian community. Momentum for change is building across the country at local government level, with a large number of councils – no doubt with a keener eye to promoting inclusion and respecting diversity in their communities – deciding to remove Christian prayers in recent years.

In Victoria, up to 40 local councillors have now signed a joint letter calling for the government to intervene in the practice of councils imposing prayers, and asking that their right to freedom from religion be protected.

At the state government level, the Victorian government has promised to develop an alternative model, one “purpose built” for the state, in its current term of parliament. And motions are likely to be debated in at least three states – New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania – in the next couple of years.

As Christian affiliation continues to plummet in the wider community – although not, perhaps, among elected representatives – we have witnessed increasingly bizarre antics at the local government level, where Christian right officeholders have sought to impose Christian acts of worship as part of meetings.

At the Adelaide City Council this year, Henry Davis carried on an obnoxious protest over a number of months following council’s decision to remove prayer, including by continuing to recite aloud Christian prayers during the moment of silent reflection and engage in heated exchanges with his colleagues. At Fraser Coast Council, following a failed attempt by non-religious councillor David Lewis to remove prayer, one councillor nearly succeeded in moving to have references to God inserted into the Acknowledgement of Country.

If other state parliaments and the federal parliament were to reform their practices, the Labor Party would have to step up. Labor politicians talk the talk on multiculturalism and diversity, and even boast about the different religious and cultural backgrounds represented among the parliamentary party. Yet, in imposing exclusively Christian prayers in state and federal parliaments, Labor could hardly be said to walk the walk.

Earlier this year, a Liberal MP said the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Labor’s Milton Dick, had been instrumental in having prayers retained as part of the Standing Orders governing the chamber’s proceedings. Dick, a Christian, told the national Christian prayer breakfast last year that the act of prayer was “unifying” for Australians.

But the practice of reciting daily Christian prayers in government institutions is far from unifying. Indeed, many elected representatives feel excluded and even stand outside their respective chambers while the practice is taking place.

Reform in the federal parliament is inevitable. At the next Census in 2026, Australians identifying as ‘not religious’ are set to overtake those identifying as Christians, and religious diversity is expected to continue to rise, too. The distance that the non-religious cohort of the population puts on Christians will be even greater if the Australian Bureau of Statistics removes – as it is considering to do – the clear bias from the religious question that assumes every respondent is religious.

So very soon the House of Representatives and the Senate will face the choice, for the first time, of imposing daily Christian prayers on a mostly non-religious population. Brave will be those Labor MPs who continue to ignore the calls for reform on this issue while chest-thumping about Australia’s multiculturalism and diversity.

When reform finally comes, let’s remember the efforts of Sue Lines and all those elected representatives, at all levels of government, who have voiced their opposition to the practice over the decades – sometimes as a solo voice against their party leaders’ wishes. Those who follow will, at least, have a chance to start their day on a higher note, and a more unifying note, than Christian prayers.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Aditya Joshi on Unsplash / Senator Sue Lines (Facebook)