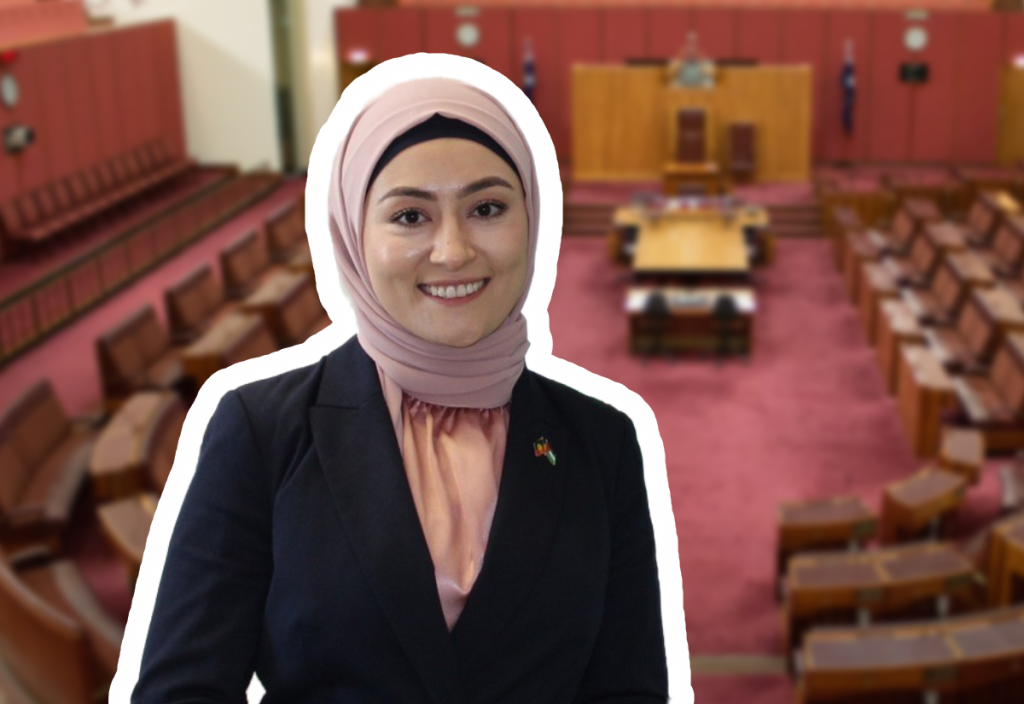

This article is based on a speech given at the Secularism Australia Conference on 2 December 2023 in Sydney.

In October, after a three-year campaign, I succeeded in removing prayer from the Governance Rules and ending the practice of starting council meetings at the City of Boroondara with an official Christian prayer.

We no longer engage in prayer at Boroondara. But with so many councils across Australia still praying, there’s a lot of work to do.

In this presentation, I will just touch on the practice of reciting prayer in local government meetings, how it works and how we can get rid of it, drawing on my experiences at the City of Boroondara.

Why is it important to remove prayer from local government meetings?

By removing prayer, we could be genuinely inclusive. It would be a hallmark of good governance. It would mean everyone could participate in the entirety of council meetings without having to participate in the religious rituals of one specific group. And it would mean that we could, as councillors, focus on what we were elected to do.

I’m not religious. I was raised without religion. My partner was raised without religion. We raise our children without religion. Despite this, after being elected I was made to take part in an official Christian prayer at the opening of each and every council meeting at Boroondara.

I have taken part in more religious rituals as a councillor than I have anywhere else in my entire life! It’s quite extraordinary.

Like most councillors, I didn’t stand for council to “advance the glory of God” – that is what our former prayer asked us to do. It’s not the role of elected councillors, and nor should it be. Our councils aren’t local churches, and we should not try to convert them into churches.

It is estimated that about one-third of councils in Australia commence their meetings with a prayer. But there are over 500 councils in Australia and circumstances are always changing. Maintaining up-to-date figures and knowing what’s going on at councils across the country is very difficult.

Figures collated by Professor Luke Beck in 2019 show that New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland are the places where the practice is most widespread.

It’s very hard to know if your council prays. Those councils that pray may or may not proscribe the prayer in any particular approved policy or document. At Boroondara, for example, we contained the prayer in the Governance Rules for a few years. Before that, we had it in a council Code of Conduct. Some councils put it in their meeting procedures. Some don’t; some just pray.

The only way you can really be certain is to actually watch the start of a council meeting or to obtain the meeting procedures. And sometimes you may not realise if it’s a council meeting or a committee meeting where it is done. Usually, it is the official council meetings where the practice happens.

How does prayer work in local government?

It varies from council to council, but there is usually one constant. And that constant is that it is almost always a Christian prayer. It is estimated that almost 90 per cent of councils with the practice have an exclusively Christian prayer.

There are a few councils that have multi-faith practices – although, I’m not very familiar with them – or rotating practices. Some councils invite external guests, such as religious leaders, to lead the prayer.

But the most typical process is the one that took place at my council – and that is where the mayor, after opening the meeting, asks councillors to stand for the prayer and leads the council in prayer. Sometimes mayors will call on a colleague to lead the council in prayer. Not surprisingly, I was never asked to lead the prayer!

When did the practice start in local government?

It’s not quite the same situation as with federal and state parliaments. There’s no tradition dating back to colonial times. By and large, the practice came to prominence, at least in Victoria and in New South Wales, in the middle of the last century.

In 1948 in Victoria, the Municipal Association of Victoria, after some lobbying from councillors involved in the association, decided to take it on as a campaign. The association got councils across Victoria to consider the practice and vote on it. So there was widespread discussion in the late 1940s. In the early 1950s, there was another push. And a similar campaign took place in New South Wales.

What is often overlooked is that there was controversy then. Despite the religious affiliation of the country at the time, not all councils immediately jumped on board; not all councillors jumped on board. Many councils did not take it on. Many councils that did take it on publicly objected to it.

What happened at my council and how did I succeed in removing the prayer?

Boroondara council was established in the mid 1990s at a time when over 70 per cent of Australians identified as Christian. The council adopted Christian prayer as a practice to open meetings. I haven’t read that there was any controversy at the time.

After I was elected in 2020, I was very uncomfortable with the practice. I thought I would start with a polite and conciliatory approach as the best way to tackle the issue with my new colleagues. I made clear my concerns and my discomfort with the practice in many internal discussions.

In the meantime – and despite the unease it caused me, and with great reluctance – I opted to stand for the prayer, knowing that very soon we would be reviewing it in our Governance Rules.

When we issued our draft Governance Rules in 2021, the report back from council officers, to my dismay, recommended including the prayer. Nine of my fellow councillors voted in support of that. Two of us – myself and one other who is a person of faith – voted against.

The Governance Rules went out for public comment. I knew that an 88-page document setting out our meeting procedures was not something that members of the public would read and write submissions on in their spare time. So I went out of my way to alert the community and the media, and everyone I could tell, as to what was going on – that there were prayer provisions in the Governance Rules and that we were praying at the start at each council meeting.

In response to that, eight of my fellow councillors lodged a formal application under the Boroondara Councillor Code of Conduct alleging misconduct for my public comments about the prayer. I’ve always considered these allegations of misconduct – which have still not been withdrawn – to be vexatious.

The community, by contrast, responded in large numbers, overwhelmingly calling for the removal of the practice and its replacement with something more inclusive, or, simply, they wanted it removed.

Such community support in my municipality isn’t surprising. In the 2021 ABS Census results, 47 per cent of my community identified as not religious. And about 40 per cent identified as Christian, with the remaining 10 per cent being from other religions or holding other worldviews.

Despite that community outcry, my colleagues still voted against – nine votes in favour of the prayer, two against. That didn’t motivate them.

I then decided to take a couple of further steps. Firstly, I responded by refusing to stand for the prayer. I gave some thought as to whether I should try to stand outside the room. In local government, it’s hard – you don’t have the time that you have in federal and state parliament to jump in and out. So I thought I would sit.

It ended up resulting in somewhat of a comical commencement to a council meeting. Everyone present except me stood for the prayer. When we moved to the Acknowledgment of Country, I stood up and half a dozen other councillors sat down. That continued to happen for every meeting after that. But the mayor then decided to say: “You can stand for the prayer if you want to.” So that was a small change.

I also joined with 20 other councillors from across Victoria in writing an open letter to the state government, the Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission, the Municipal Association of Victoria, and other bodies, opposing the practice of including religious worship in council meetings and urging them to protect freedom from religion.

Both of these measures – sitting down and the open letter – generated more public attention and criticism of the practice. But they didn’t change the situation materially. It was the potential unlawful nature of the prayer, and the legal challenge, that eventually led to its downfall.

So being left with no option – and with the support of Professor Luke Beck from Monash University – I sought legal advice and support from law firm Maurice Blackburn. In January 2023, my lawyers sent council a letter of demand. And this is what changed everything.

The letter advised that the prayer was: firstly, in breach of the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities; and, secondly, ultra vires in that it went beyond the powers of local councils and was not authorised by the Victorian Local Government Act. And, to make it stronger, the letter of demand – and this is important – had a draft statement of claim attached, demonstrating that I was ready and willing to commence court proceedings if my fellow colleagues didn’t back down.

In response, a month later in February, Boroondara council temporarily stopped praying at council meetings and resolved to consult again on the removal of the prayer with the public. Hundreds of submissions were received – again – and 86 per cent of them called for the removal of the prayer.

In October, Boroondara council resolved 10 votes to one to remove the prayer from our Governance Rules, thereby ending the practice altogether.

What’s interesting to know is that regardless of those community views – and they were very clear; it was a very strong message – a number of my colleagues made it very clear that they were doing so begrudgingly and because they felt compelled to do so. It was not because they were listening to the community. That was not the material factor that changed their decision.

As a result of them backing down, it meant that the matter didn’t proceed to court. Had it proceeded to court, and if we obtained a court judgement that it was unlawful, it would have had implications for local government across the board – at least in Victoria.

But at least a cloud has been cast over the legality of the practice. Maurice Blackburn considered the practice at Boroondara to be unlawful, as did the three barristers that worked on my case. Professor Luke Beck has published a peer-reviewed academic paper arguing that the practice in local government in Australia is unlawful.

Where do we go from here?

For the next steps, I think we need to find councillors to be not only willing to speak out and vote against the prayer and comment but potentially willing to consider legally challenging the practice in their municipality.

It’s hard to find councillors and encourage councillors to speak out. Especially if they’re in a minority, it’s not easy.

There are various barriers. There are costs associated with obtaining legal advice, costs associated with undertaking potential court proceedings, potential adverse costs order if the case were to be lost. There is the potential to damage relationships with fellow councillors and the voter backlash that some fear from those in the community who want the prayer retained.

And this is another one I want to make clear: there’s the potential of forgoing the opportunity of being appointed mayor or deputy mayor, or similar appointments. In the case of these positions, they come well-remunerated. At Boroondara, the mayor receives an extra $100,000 and the deputy mayor receives an extra $50,000.

I’m not saying this was the case at Boroondara; it is a case across the board. I have spoken to councillors in Victoria who have said they are concerned they could forgo opportunities and perhaps miss out if they take on an issue that’s important to them.

Going forward, I want to help continue with this campaign. I don’t see it as having ended until the practice is stopped across the board across Australia. I’m going to work to reach out to additional councillors and see if we can provide support and potentially develop a broader campaign – ‘Councillors for Secular Local Government’ – to provide support and assistance for those who might be willing to consider those additional steps and potentially willing to consider legal action. I think that is the way we can go forward.

I will leave you with one request. Reach out to your local councillor – your ward councillor or councillors. Find out if your council is praying and if there are any councillors that might be willing to take the case further.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Amaury Gutierrez on Unsplash.