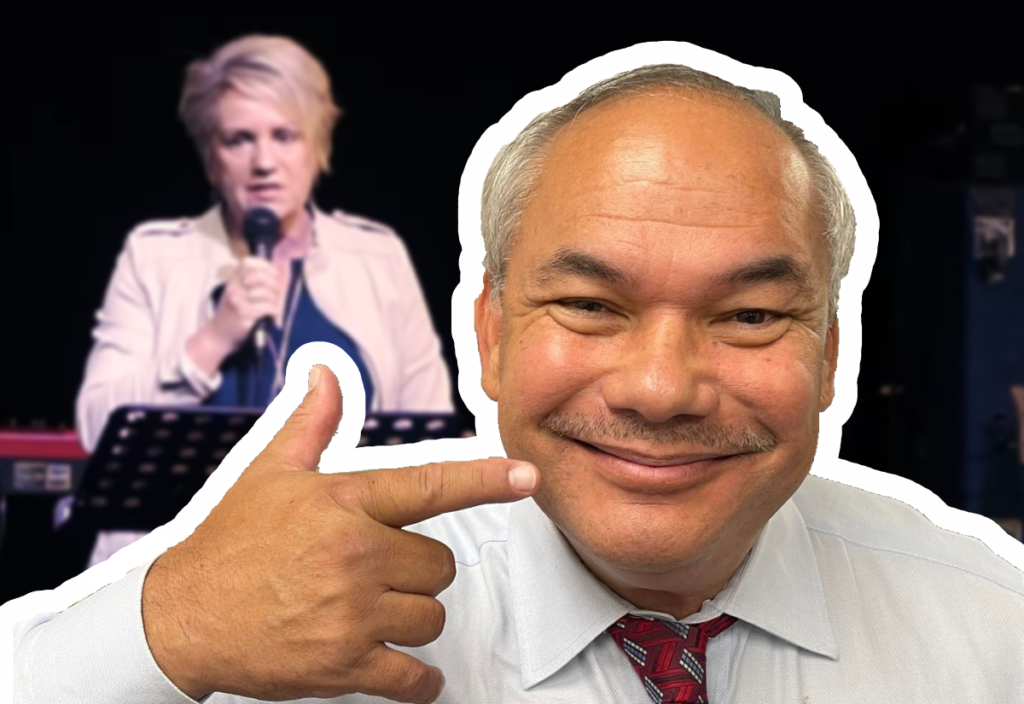

On Easter Saturday, The Australian was to run a 1200-word piece of mine about Mathias Cormann being a safe pair of hands at the OECD, in a troubled time, or so I thought. It didn’t get onto the page, or even the online version of the paper. But the paper’s foreign editor, Greg Sheridan, was given some 3000 words to expound his Catholic religious beliefs.

I read his piece with disbelief – both in the sense that I do not share his religious beliefs and in the sense that I could not believe that he had been given so much space to preach specifically that, at the end of the world, all of us would undergo ‘bodily resurrection’ and would live forever on a transformed Earth, which would be the promised ‘Heaven’. This essay is an attempt to express my sense of disbelief to a rationalist audience.

Sheridan spent about half of his piece telling us a quite poignant story about his sister Bernadette dying of cancer after a seven-year struggle. I shall leave that to one side. What astounded me was his ingenuous doctrinal annunciation that Jesus both rose from the dead and, in doing so, ‘defeated’ death for all of us, so that we could all look forward to bodily resurrection.

“This isn’t a fringe belief, but a central teaching” of Christianity, he declared, early in his piece. He immediately commented that “the best chance for Christianity to grow again in the West is not to hide but to proclaim its radically weird teachings.” Note the phrasing.

He declares that the religious beliefs of both Scott Morrison and Dominic Perrottet lost out politically because their conservative Christian beliefs cost them votes. Yet he insists that what Catholicism and other Christian denominations need to do is double down on teaching ‘supernatural beliefs’.

He wrote:

“Christianity is a supernatural religion, with vast spiritual and eternal claims. Everything about it is radical and a bit wild. Christianity is a faith that offers comfort and acceptance, but it’s also a faith of repentance, commitment, life change, prayer and forgiveness, and the unnatural practice of putting others first. It provides space for all the passionate heroism, meaning and destiny life can contrive. It’s bold, not bland.”

As someone raised a Catholic and one who has studied both the history of Christianity and the theology, I do not fault his account of what it has been about. What I take issue with is the very idea of the ‘supernatural’ as something worthy of being taught in our time.

Above all, I find his next claim, the one about bodily resurrection in no sense ‘radical’, as he claims, but most certainly ‘weird’, as he confesses it is.

He quotes St Paul’s first and second epistles to the Corinthians without the least acknowledgement that what someone claimed to be true two thousand years ago does not have intrinsic, much less authoritative, credibility. He adds:

“These are not isolated references in the New Testament. Nobody much beyond religiously devoted folks reads it these days, so its spiritual radicalism, its uncompromising, revolutionary vision about the destiny and the dignity of every human being, has slipped away from popular consciousness.”

Why does such a conservative individual suddenly give weight to terms like ‘radicalism’ and ‘revolutionary’? Or, for that matter, ‘uncompromising’.

He seeks to lend his piece gravitas by quoting Roger Scruton, Thomas Aquinas and St Irenaeus (a second-century CE theologian), without at any point asking himself why their claims should be believed. He may have read the New Testament, as well as Scruton, Aquinas and Irenaeus, whether in the original or at second hand, but he seems desperately short on analytic philosophy and critical thinking, to say nothing of physics or biology.

He uncritically states that Aquinas “deduced that human bodies in paradise would not experience decay or suffering” and “would do whatever the soul commanded”. They “would be able to move through solid forces, as the risen Jesus moved through walls”.

I read all this, in a serious newspaper, with stunned incredulity. Aquinas (1225-1274) was born some eight centuries ago. Has it not occurred to Sheridan that knowledge has come a very long way since then?

But it gets worse. He proceeds immediately to state, “The Christian teaching that all human beings will live forever in physical bodies has big implications for heaven.” Heaven will be a place, he says, and that place “will be right here, but here will be transformed.” Pardon me?

Sheridan’s sources for this are far older even than Aquinas: St Paul and Irenaeus. The latter, he portentously points out, was taught by Polycarp, who was taught by John the Apostle. So there!

The Christian vision, he declares, unlike either classical Gnosticism, which condemned the body in the name of the soul, or modern materialism, which rejects the idea of the soul in the name of the body, unites body and soul. How do we know? Because St Paul asserted in letters to believers, almost 2000 years ago that Jesus had defeated death and that all of us will enjoy a bodily resurrection thanks to the risen Jesus.

“The resurrection of the body”, he concludes (before proceeding to discuss his sister’s death), “is not theoretical. It’s weird, like many things that are deeply true, and it’s a central Christian belief. At Easter it’s worth remembering, and celebrating.” Yet he at no point explains what precisely he means by the term ‘deeply true’.

He might, perhaps, have attempted a bit of sophistry by declaring that much of particle physics is “weird, but deeply true”. But so committed is he to his confessedly ‘weird’ beliefs that he didn’t even offer tendentious analogies – only Christian doctrine.

Of course, any such analogy with physical science would break down because the latter could be explained systematically and would not be dependent on doctrinal authority, to say nothing of old books of ‘revelation’ or the blessed ‘magisterium’ of a priestly caste.

It has mystified me ever since I came of age that anyone could believe, in our time, what Sheridan, without the least sign of self-consciousness, expounded this Easter as true and important tenets of his religion.

I have spent decades attempting to understand religion in general and Catholicism in particular. Yet still I was shocked that his column would appear in a serious newspaper.

To that, of course, some of you might retort that The Australian should not be regarded as a serious newspaper. It is just that, however, and I write for it on many serious subjects and have a national readership for what I write.

I know its politics and social outlook are broadly conservative, but nonetheless I was taken aback when I read Sheridan’s remarkable profession of supernatural belief.

So, here’s the challenge: How should a secular rationalist respond to such claims as those Sheridan makes? One option, of course, is scornful dismissal, which is very tempting, but leaves him all the latitude in the world among the committed and the credulous.

Another would be to make a straightforward case that everything we know about biology counts against his supernatural belief. But that would very likely fetch the response – if it drew one at all – to the effect that one cannot refute the ‘supernatural’ by reference to the ‘natural’. That’s a stock standard retort from believers to the claims of science bearing on their ‘weird’ – Sheridan’s word – beliefs.

There is a third option, but it is a radical and demanding one. That is to take up the philosophical cudgels and make the case not only for a scientific world view as against a religious one, but for the emancipatory and elevating virtues of secular philosophy and science as against religious belief. That is to say, to engage in the great conversation of the Enlightenment versus religion.

What needs to be acknowledged, however, in going down that path is that very large numbers of ordinary human beings cannot fathom the complexities of that debate and are susceptible to religious or other cranky doctrines just because they seem to provide relief from the overwhelming or disheartening or boring realities of the lives those people live.

This is more so now and, arguably, more true than it was even a decade or two ago, at least seen on a global level. That raises what, it seems to me, are actually very interesting questions and challenges. Above all, it means that we need to invent means for reaching out to believers and offering them authentic substitutes for what induces them, psychologically and socially, to adhere to beliefs with which we disagree.

In that quest, I submit, there is a great need for us to at least understand the nature and evolution of religion as such and the phenomenology of religious belief.

If Sheridan had confined himself to arguing that Christian belief in the resurrection and the resurrection of all bodies had been part of a human search for transcendence and hope, we would have had enough common ground for a discussion. But his insistence that it is true and ought be embraced as such is a roadblock to fruitful conversation, on the face of it.

In my biography of a great, if heretical, Catholic mentor and friend, The Secret Gospel According to Mark: The Extraordinary Life of a Catholic Existentialist, published six years ago, I attempted to explore this terrain. I know Catholics who have said to me that they love what I did and that it spoke to them about their own life journeys and changing beliefs. But Sheridan? I don’t believe he would so much as read it.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Australia India Institute on Flickr (CC)

In regards to Greg Sheridan’s uncritical supernaturalism

Paul, I don’t say I disagree with you, and I certainly can’t say I agree with Greg Sheridan’s The Australian piece. But for context, Sheridan’s Easter essay is no seminal piece of work – his views are well documented, if no where else, than his most recent book, Christians, the urgent case for Jesus in our world. Apparently, it’s a best seller….

But your argument suggesting that biology counts against the supernatural might be contested by some. Evidently, human spirituality is influenced by heredity and that a specific gene, called vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), predisposes humans towards spiritual or mystic experiences. The so-called God gene hypothesis is based on a combination of behavioral genetic, neurobiological and psychological studies. The major arguments of the hypothesis are spirituality can be quantified by psychometric measurements; and that the underlying tendency to spirituality is partially heritable.