Hillsong was first formed in 1983 by Brian and Bobbie Houston as the “decidedly functional, even dowdy” The Hills Christian Life Centre, in outer-suburban Sydney. Now one of Australia’s most recognisable Pentecostal megachurches, it has congregations and campuses across the globe.

In recent years, “unlikely king” Brian got widespread attention as a “close friend” of Scott Morrison, who had regularly attended Horizon Church, founded by a former Hillsong pastor, before he became Australia’s prime minister.

However, Houston resigned in March last year, after allegations of inappropriate conduct of “serious concern” with two women.

In the same month, Hillsong was accused in Australia’s parliament of “fraud, money laundering and tax evasion”. And, last August, Houston was found not guilty of charges of covering up sexual abuse by his pastor father Frank, whom he described as a “serial paedophile”. (The court accepted Brian’s claim his father’s victim had asked him not to report to police.)

In the last two years, there have been two four-part documentary series, a podcast and and an SBS documentary on Hillsong.

Now, Crikey journalist David Hardaker tells the story of Hillsong in his new book, Mine is the Kingdom.

How did Hillsong come to dominate Australian Pentecostalism – and Australian Christianity more broadly? Through the 1990s and 2000s, Hillsong drew crowds and attention: it was young, vibrant and popular. Until at least 2016, Pentecostal churches were growing while other Christian churches were declining.

Hardaker tells the story of Hillsong by charting Houston’s ministry through a “rise and fall” narrative, in which the success and failure of Hillsong and Houston become one and the same. For Hardaker, “Hillsong was Houston, and Houston was Hillsong. It was a concentration of fame and power not possible in the traditional Christian denominations.”

He begins by depicting Brian Houston as a boy from New Zealand who “inherited his father’s name as a leading New Zealand preacher, but not much in the way of wealth”. The Houstons moved to Sydney in the 1970s after Frank Houston received “a picture of Sydney, Australia” and a divine message to start a church there.

Hardaker presents Frank and Brian Houston as “outsiders” who “moved to the very top of the Assemblies of God movement in Australia”. He then documents the early contributions of other key players, drawing on a mix of news sources, documentaries and interviews conducted for the book.

Hillsong is known for its music. While music production is not central to the book, one chapter begins with former music pastor Geoff Bullock, who left his ABC job in the late 1980s to work for Hillsong full-time. He left the church in 1995, after 12 years, deciding he no longer shared its vision.

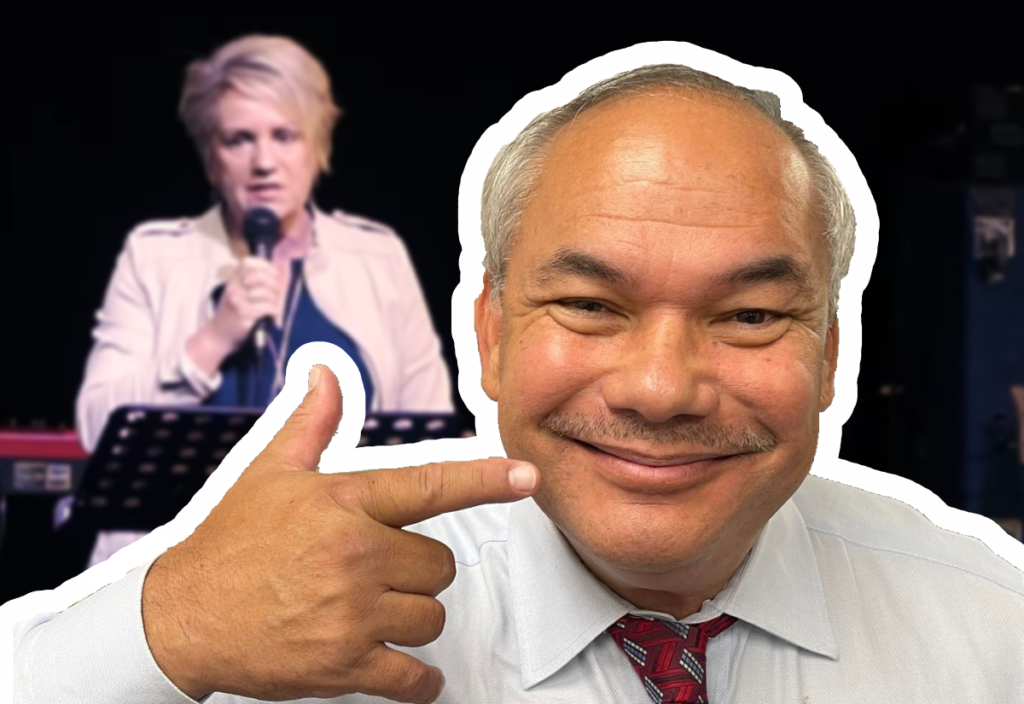

This chapter also introduces Nabi Saleh, former co-owner of Gloria Jeans coffee chain, who is described as a “fabulously wealthy” donor and key advisor to Houston. Hardaker shows how the business interests of Gloria Jeans and Hillsong were often “symbiotic”, with coffee shops on site at Hillsong churches and Gloria Jeans franchises owned by Hillsong attendees (who returned financial tithes or donations to the church).

He details how Saleh cultivated relationships with leading American evangelical preachers, including two, Casey Treat and Rick Godwin (also authors and motivational speakers) who were “among the most influential” in Houston’s life.

In the second half of the book, Hardaker moves on to discuss “the sins of the son”. He begins by turning to an incident in 2019, when Houston spent 40 minutes in a hotel room with a woman “known to Houston as a financial supporter of the church”.

Little detail is known about this incident, and Hillsong has stated Houston can’t recall what happened in the room, as he was under the influence of alcohol while taking anxiety medication.

Hardaker also focuses on the mishandling of complaints made by Anna Crenshaw, who was assaulted by Jason Mays, an administrator and volunteer singer at Hillsong, at a party in 2016. She was 18. She says Hillsong only took her complaint seriously and notified police after her father, an influential American pastor, pushed church leaders to act. Hardaker describes this as starting Hillsong’s “own #MeToo movement”.

Hardaker records that one young woman, Helen Smith, said after the Crenshaw incident:

I wasn’t sure that I was okay with taking my kids to church, which is what I grew up expecting I would do. I didn’t see it as a safe place anymore for me or my children. The way they handle serious allegations, they think that they’re above the law.

In documenting these accounts, Hardaker is compelling, while largely resisting sensationalism.

In the next chapter, Hardaker takes us back to 1995. He describes the burnout experienced by volunteer music and production crews. Bullock re-enters the story, and recalls telling Houston, “Listen, if we keep going this hard, it’s gonna break.”

“This was a spiritual home for them and they were just working like dogs,” he reflects. Houston apparently had little concern, dismissing Bullock by saying, “you’re not a union rep […] if they don’t like it […] Go to another church.”

Houston’s response is certainly uncaring. Yet, churches typically rely on volunteer labour and Hillsong is no different in this sense. As Hardaker notes, “Hillsong’s music had taken off worldwide and was set to become the river of gold that would fund the church’s expansion.”

Hardaker describes Houston’s dream of “a world beyond borders, where Hillsong and Pentecostal Christianity would reign”. Houston, who “ruled the roost” as a “salesman” for Jesus, is described throughout using images of monarchical rule, sales and showmanship.

Hardaker is interested in another rise and fall, too. Hardaker weaves Houston’s story with that of Scott Morrison, whom he works to “unravel”. The first chapter sets up this dual narrative by recounting the moment “the two men – the pastor and the politician – prayed on stage together”, at the 2019 Hillsong conference. “Both of them, at this moment, were at the peak of their powers.”

This pairing is an interesting aspect of Hardaker’s book – one I wish had featured more prominently.

The convergence of Pentecostal theologies and neoliberal ideologies is embedded in the text, but underexplored. Early on, Hardaker uses Morrison’s oft-repeated refrain, “If you have a go, you’ll get a go”, to introduce the concept of prosperity teaching and to frame the wealth of the Houstons and Hillsong

As the Houston story would show, all things were possible if you had the spirit to spread the word of Jesus Christ. If you had a go you would certainly get a go – and a God-given go at that.

Hardaker explains that within prosperity teaching, the word “blessing” has:

…an overt meaning of “material blessing”. It was based on an interpretation of the Bible that Christ lived in poverty while on earth so that we could live well and be removed from the curse of poverty. […] if we did not claim our rightful blessings as Children of God, then we were wasting the life of poverty that Christ had led.

This is a risky lesson. Hardaker rightly notes it “has the effect of demonising the poor: if you are wealthy because you believe in God, then the flip side is that you are poor because you lack faith.”

Pentecostalism’s creep into Morrison’s politics emerges as a key issue. Hardaker contends:

In some ways, Houston’s brand of prosperity Pentecostalism is so perfectly intertwined with neoliberal thinking that it is difficult to say where the religion stops and the political policy begins.

Though Australians tend to feel uneasy when they see religion creeping into public life, Christianity has long been part of it – through policy, education, church-based charity and welfare.

Pentecostal leaders and churches who embody the neoliberal values of individualism, competition, market value and merit are not merely influencing politics – they are responding to neoliberal conditions.

As pastors and politicians continue to “rise and fall”, we need to look to the systems and cultures that enable them.

Brian Houston is not the first evangelical leader to “rise and fall”. Hardaker tells us other global ministers Houston had been close to falling from grace long before he did.

Hardaker illustrates a “familiar pattern”. South Korea’s David Yonggi Cho embezzled church funds. In the US, Jim Bakker was found to have sexually assaulted a church staff member and committed fraud.

“Rise and fall” narratives bring us into the lives of powerful leaders and show how the worlds they create spectacularly fall apart. As outsiders looking in, the personal drama is part of the appeal.

The problem? Such narratives frame these once-powerful leaders as the source of trouble. If only we could be rid of such people, churches (and parliament) might be safer, healthier places! It is an enticing idea.

However, we need to look beyond analysing the actions of any individual church leader. We need to ask what sort of systems allow abuses of power to happen again and again.

In her analysis of the now-dissolved American megachurch Mars Hill, anthropologist Jessica Johnson argues we should not view abuse of spiritual authority as the isolated acts of a few bad men – the supposed rotten apples. Rather, we need to attend to the networks and systems that support and produce the kind of hierarchical leadership which parishioners do not feel safe to question.

If we want a healthier Hillsong, we cannot look just to Brian Houston. While he may have been the founder and face of the movement, the movement is bigger than him.

Throughout the book, Hardaker points to a lack of institutional accountability to explain both the minimisation of Frank Houston’s crimes and the “reign” of Brian. Hillsong’s elders were apparently unaware of how Brian Houston operated as global pastor:

Hillsong’s elders are the church’s most illustrious figures; some date their association with the church back to its earliest days. They are meant to act as spiritual counsellors and to provide wise advice to the church, But they were now hearing disturbing details about Brian’s behaviours for the first time.

This raises more questions than it answers. If a church has elders who are charged with providing spiritual care, how can a king-like leader rise without being kept in check – and without being cared for? Is a leader only in need of oversight after they fall? And then, are they cared for or cast aside? How can we make sure such a figure does not rise again?

Who actually cares for men like Brian Houston? I mean that in its most generous sense. Houston was successful. Hardaker asks: “So why the pills? And why the booze?”. He refers us to an interview Houston gave in 2018:

I was overseeing a whole movement of churches in Australia, eleven hundred churches. I sort of dealt with it as a church level and on a father level … but I’ve probably never, ever really looked after myself, and the grieving and the impact on myself. So from that point – over the next, maybe, ten to twelve years – I think, slowly, I was winding down emotionally.

Neoliberal conditions push us to be responsible for our “own wellbeing and self-care”. Yet, at the same time, the need to work, to make money, to be bigger and better, often robs us of the ability to genuinely care for ourselves or our communities.

I’m wary of being overly sympathetic towards Brian Houston, but for the sake of the community of believers who were under his “care”, we need to ask: who is making sure these people and their leaders are genuinely cared for?

Houston may have cared for his own material wealth, but did he have the capacity to care for his spiritual and emotional health, to seek help when it was needed or to genuinely care for others?

As Hardaker acknowledges, within Pentecostal Christianity “the extraordinary reigns” and miracles are commonplace. Christianity itself is centred on the belief the dead do rise.

Phil Dooley, the new global pastor of Hillsong, wants Hillsong under his leadership to be a “healthier” church. Brian and Bobbie Houston have announced on social media they’re starting a new online ministry and church.

As we plot the rise and fall – and potential rebirth – of churches such as Hillsong, we should leave space in the narrative to carefully attend to the ways churches and their leaders are safeguarding against spiritual, financial and sexual harm.

We should care that Christian leaders are cared for, so they may be able to care for those in their community.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

David Hardaker, author of Mine is the Kingdom, will appear as a guest speaker at the next RSA Webinar on Wednesday 10 April. For more information about the webinar, and to register to attend, visit the Rationalist Society of Australia’s website.

Photo by David Libeert on Unsplash.