Demonising secularism has become something of a sport for the religious right in the United States. Secularists are routinely painted as ‘aggressive’ or ‘militant’, often with allusions to 20th-century totalitarian regimes. Secularism becomes a Stalinist strawman rising as the enemy of all faith. In culture war rhetoric, truth is often the first casualty.

“Secularism must be the most misunderstood and mangled ism in the American political lexicon”. So observes Jacques Berlinerblau, a US commentator on secularism and a professor of Jewish civilisation.

Clearly, Australia is not immune. In his open letter to Jane Caro on the subject of the school chaplaincy program, John Dickson, founding director of the Centre for Public Christianity, provides an example par excellence of the strange sport of secularism bashing.

Dickson describes secularism as: “…an ideology that seeks to keep religion out of important aspects of the life of our community.” Dickson has mangled it completely.

Secularism represents the separation of church and state, designed to protect the religious liberty of citizens, and place appropriate limits on the power of faith groups given their plurality.

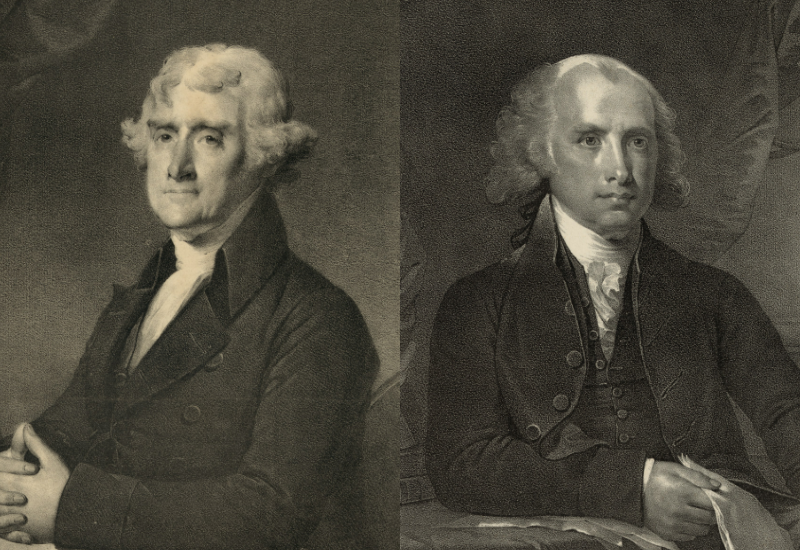

The seed of secularism was religious liberty. The seed was sown by James Madison in the United States with the Establishment Clause, and by our governments in Australia with Section 116 of the Constitution. The impetus was preserving the religious freedom of vulnerable Christian sects. As well as Christians, secularism protects Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, people of other faiths and also … non-believers. Yes, religious liberty belongs to non-believers, too!

Even Dickson’s old mate at the Centre for Public Christianity, Michael Bird, disagrees with him (2015): “…secularism emerged in Christian Europe as a way of dissolving religious sectarianism, neutering the political ambitions of the Church and promoting religious freedom. The Australian constitution was drawn up in this context, and Australia was intended as a secular nation.”

Secularism has never been about the erasure of religion from the public sphere. That’s not what Australian freethinking groups want. Nevertheless, any argument questioning the role of faith in the public arena, such as Caro’s original article on Rationale, receives the same predictable response.

Secularism has never been about the erasure of religion from the public sphere. That’s not what Australian freethinking groups want.

Dickson asks, “Isn’t your article contending for religion’s ‘inferiority’ to your particular version of secularism?” He argues that Caro seems “driven by a personal distaste of religion”, as if this should invalidate her views. But it’s actually the crux of the issue. Caro is entitled to hold a negative view of Christianity, just as Dickson is entitled to his negative view of atheism. Their disagreement is the very reason we have a secular society. That’s the point! And, sorry, not everyone wants Christianity presented to their children in schools.

Clearly, the religious right frame this debate as a category error – secularism versus religion (Christianity) – when, in fact, secularism is neutral towards all belief systems, vouchsafing the freedom of all.

Secularism is not a religion. It is not opposed to Christianity. The only conflict exists when there is disagreement on the appropriateness of religious programmes in the public realm.

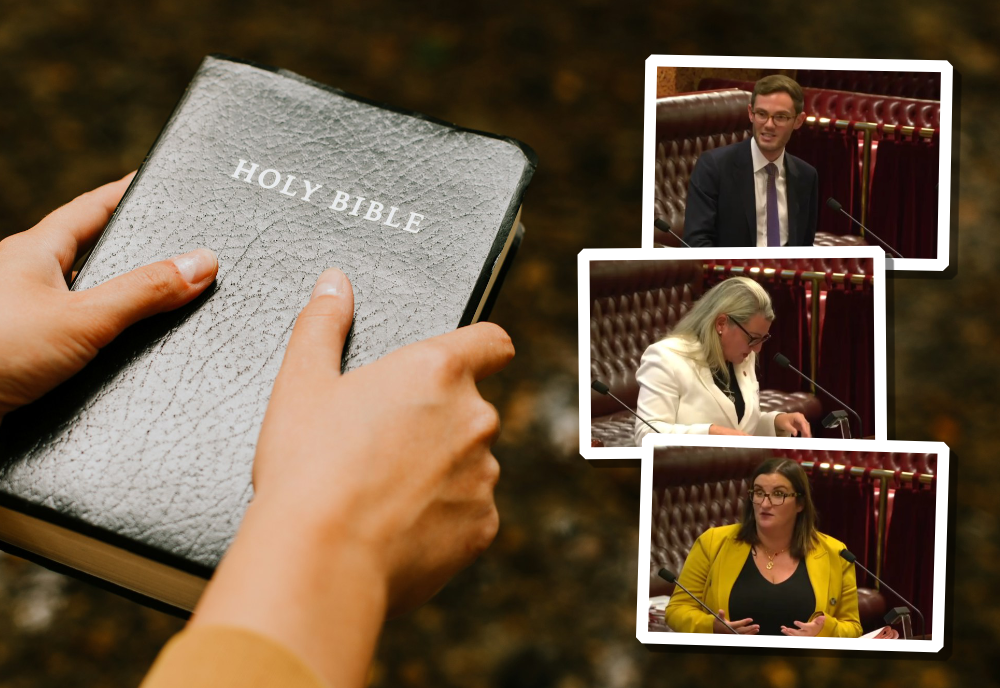

Dickson wants to know what’s so offensive about the chaplaincy program. The Australian taxpayer funds the provision of chaplains to provide pastoral care and counselling to students at a cost of $61 million dollars per year. The program specifically excludes non-religious counsellors from providing services.

Over 30 per cent of our citizens are non-believers – a figure sure to increase with the imminent release of the Census results. Funding exclusively religious workers to provide services which can equally be provided by non-religious workers is discriminatory and at odds with our secular ideal. As Caro notes, public schools were meant to be “compulsory, secular and free”.

Caro argues that “Christianity sneers at the central virtue of public education” which is “welcoming every child as equally important”. But, according to Dickson, Caro’s argument can’t be right, because, well, guess what? “Jesus Christ … gave the West its prized doctrine of human equality”. Well, praise the Lord and thank you, Jesus!

But I’m afraid Dickson misses the point entirely. Newsflash: many school children come from non-Christian and non-religious homes. Why must we have only religious chappies? Why not an equal playing field?

In fact, if Jesus gave us equality, why isn’t Dickson dancing, whooping and praising Jesus for all that equality and fairness that a secular chaplaincy program would offer?

Dickson then takes issue with Caro’s remark: “Education is meant to teach children how to think, not what to think”. Wrong, according to Dickson, because learning is impossible without content transmission – i.e. mathematics, science, et cetera. He’s correct there, but again, misses the point entirely.

Yes, indeed, we need facts. Facts are good. But we all know exactly what the “how to think, not what to think” aphorism means: we shouldn’t present opinions as if they were facts. “What to think” is not facts, but beliefs and opinions. I can’t see how changing chaplaincy to remove its inherent discrimination will result in a ban on facts.

And, yet, Dickson’s letter is replete with beliefs posing as facts. For instance, did you know “religion illuminates all intellectual disciplines”? Did Jesus invent equality? Is chaplaincy voluntary? No. Do either students or parents have a choice here? Does the taxpayer choose whether to chip in for the funding? No. The only choice schools have is to accept the funding and employ a religious chaplain or not to accept and not get the additional support at all. Why would they say no?

As Dickson noted, facts are rather important to education. And the extent to which the facts have gone missing in Dickson’s article should give us pause to consider a more secular approach to schooling.

Understanding secularism can’t be this hard. We have moved on from a practically universally Christian nation, and we still have elements of public life where Christianity retains undue influence. It’s no coincidence that the enemies of secularism are so often pushing a Christian barrow.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photos by MChe Lee on Unsplash and www.johndickson.org/bio