António Guterres understands something that most world leaders do not. He knows that exponential growth is unrelenting and immensely destructive. This is why climate change is so precipitous. No matter how forcefully Guterres urges immediate action, governments prevaricate, ignore it, or deny it even exists.

Doing business as normal is familiar and politically safe. The ‘growth is essential’ strategy has worked well for us if you are not worried about equity and equality. Over the last 200 years humans have been amazingly successful. While this success may have come at the expense of many, and been patchy in its effect around the world, on the whole it has had a remarkable effect on the quality of life of ordinary people.

Many people who live in well-developed and wealthy countries can honestly say they have lived in the best of times. So many of the developments in the last 200 hundred years have been extraordinary and unprecedented. They include: the industrial revolution; advances in science and technology, medicine and health care, and food production; the creation of democracies; and improved social justice and working conditions.

The benefits of these developments were so obvious that few foresaw the problems that would accumulate from these initiatives to save lives, improve life for people, and to make money. The changes were hardly noticeable at first. The slow beginnings of exponential growth is one of the reasons most people do not understand it.

Consider the familiar example of what happens if you put one grain of rice on a chess board, then double it so that there are two on the next one, then four and then eight, and so on. It doesn’t seem very drastic, but the gap in rice grains on one square and the next is getting greater each time. By the time you get to the 64th square, you end up with a total of 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 grains of rice on the chessboard. This is what happens with exponential growth.

Since the start of the industrial revolution, improvements have built on those that have gone before, causing exponential growth in many areas of human endeavour. The net result of that growth is that we are now at the point where our very success will lead to our failure as a species and as stewards of the Earth.

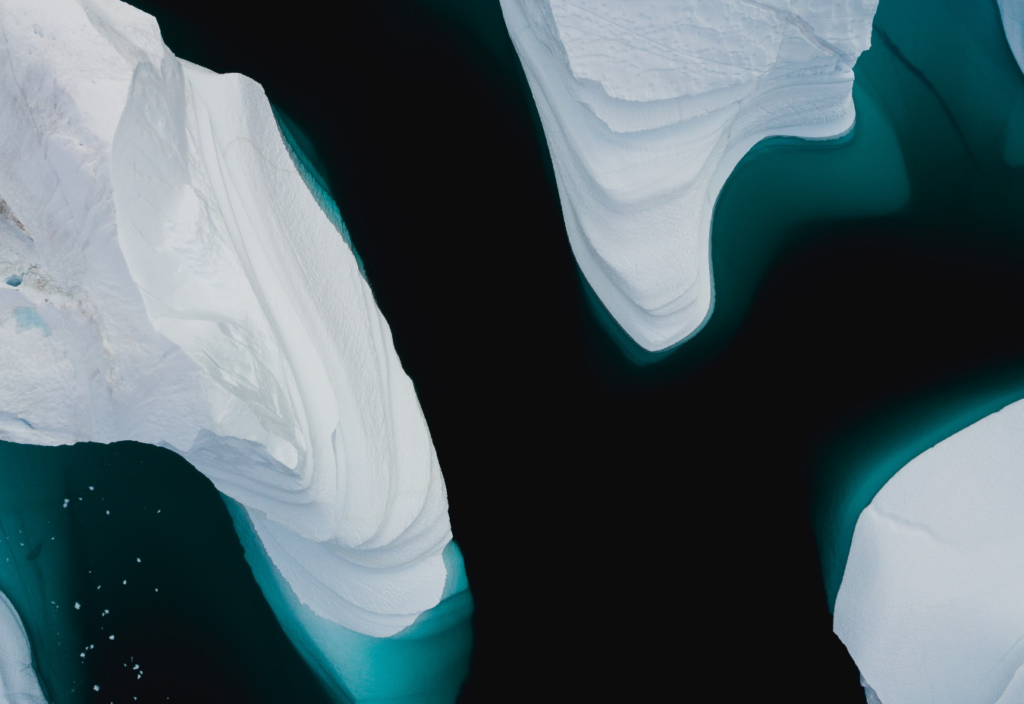

Three areas of exponential growth – population, wealth and consumption – are responsible for most of the existential problems facing us now. They have driven an exponential or near exponential growth in: global warming; anthropogenic mass; clearing of natural ecosystems; plastic waste; health care costs; wealth of elites; numbers of smartphones; influencers online; tourists numbers; global GDP ; food waste; artificial intelligence; drone usage; antibiotic resistance; use of water; melting of glaciers; viral Zoonotic diseases; resource consumption; and so on.

Exponential growth is the reason we can go from success to failure in an instant. Of course, other factors will come into play in the real world.

Nothing illustrates the problem with exponential growth than human population expansion. After thousands of years of slow increase, at around 1800 the population growth rate began to increase. The world went from a population under one billion people in 1800 to over eight billion today.

While we can still help people to have smaller families, and the growth rate is dropping, we are likely to reach between 10-13 billion people in the world by the end of this century. This population may be unsustainable.

Another example of exponential growth is growth in wealth. Many ordinary people, especially those in well-developed democratic countries, are better off than ordinary people have been in the past. At the same time, a greater proportion of the wealth of the world is being concentrated into the hands of a smaller number of people, leading to greater inequality. The numbers of people living in extreme poverty has not changed since the 1990s.

The exponential growth in human population and wealth has fuelled many changes in the world, mainly because they have led to a huge increase in the human consumption of the resources of the Earth. This is encouraged by economies based on ever increasing growth.

Since the start of the industrial revolution, improvements have built on those that have gone before, causing exponential growth in many areas of human endeavour.

In a comprehensive report in 2025, Ivan Johnstone commented that the economic growth rate of 3 per cent per year, advocated by some economists, would be exponential and would require, over the next 24 years, the use of as much energy as has been used since 1800 until 2020.

The growth in motor vehicles is an example of exponential growth in consumption. Practical motor vehicles were first produced at the end of the nineteenth century and start of the twentieth century. However, they were expensive and not readily available. Then Henry Ford had the innovative idea of mass production. Owning one of his classic Model T motor cars became a possibility for the general public.

Cars and other vehicles gave people immense freedom to travel for work and pleasure, and to go where they wanted, when they wanted, in comfort. Before trains and bicycles, most people were restricted to how far they could walk, only well-off people could afford a horse or two and a carriage.

From 1921-30, the average number of people per vehicle in Australia dropped from 45 to 11. Car ownership boomed after the Second World War. By 1990, there were nearly 500 million cars in the world. In 2024, it is estimated there were 1.47 billion cars, including trucks and SUVs. That is one car for every 5.5 people in the world. The growth in car ownership has been almost exponential.

Before the industrial revolution, when people only had to worry about burping cattle, smoke from burning wood and charcoal, and the occasional exploding volcano, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere was 288 parts per million (ppm). In May 2024, carbon dioxide hit just under 427 ppm — a new record. This change was the result of human activities and produced the current level of CO2 in the atmosphere that has not been reached for at least 800 millennia.

Globally, transportation, including road vehicles, accounts for roughly one-fifth of total CO2 emissions. Road vehicles are the largest contributor within the transportation sector, followed by shipping and aviation. In 2023, global road vehicles emitted over six billion metric tons of CO2, with cars and vans accounting for more than 3.8 billion tons.

Added to the problem of too many cars and other fossil fuel driven vehicles is the fact that one of the major greenhouse gases produced by them (carbon dioxide) can last in the atmosphere for hundreds, even thousands of years. Another greenhouse gas produced by cars, nitrous oxide, can last around 100 years. Methane, another greenhouse gas, usually dissipates within a decade, but it is a much more powerful greenhouse gas than CO2.

Since 2013, sales of electric cars have increased almost exponentially. This gives some hope that eventually most people will drive electric vehicles, and that this will benefit commuters and the environment. Unfortunately, growth in larger cars has also become exponential, off-setting the contribution of electric cars to reducing global warming. In Australia, SUVs have surged from around 22.7 per cent of new vehicle sales in 2010 to over 50 per cent in 2020. In 2022, 330 million SUVs emitted one billion tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Many people are trying hard to reduce these existential threats posed by our very success, and there has been progress. But saving the planet still seems overwhelming given how little time we have to reverse adverse changes to the planet and human societies in particular. We need governments to ramp up their actions.

New research from Harvard indicates that it only takes a small minority of people to change the world. If 3.5 per cent of the population undertakes sustained, non-violent forms of resistance to what is wrong in the world, then change will happen. You don’t have to be extreme or violent to have an impact on those in power. You just have to turn up. In Australia, 840, 000 people would be needed.

In the meantime, we could continue to drastically decrease our consumption and the waste we produce, and be very particular about what we buy. And, of course, there are ways we succeed and fail that are not related to exponential growth – such as the many ways we are willing to help people or hurt them. But that is another story.

Published 7 August 2025.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Carlos Irineu da Costa on Unsplash.