A new Pew Research Center study assesses public opinion about the importance of their national leader’s religion and religiosity. It’s worth a look because it reveals some important insights.

What the study measured

The public in many countries were asked about the personal importance of whether the Prime Minister or President: 1) has religious beliefs that are the same as your own; 2) has strong religious beliefs, even if they are different from your own; 3) stands up for people with your religious beliefs.

Respondents chose between “very”, “somewhat”, “not too” and “not at all” important. Those who answered “very” or “somewhat” were aggregated into “important”.

For domestic relevance, I’ll confine my remarks to the WEIRD (Westernised, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic) English-speaking countries: United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and Australia. Neither Ireland nor New Zealand were included.

I’ve also done the calculations to determine if answers are statistically different between these countries.

Australia least ‘religiously political’

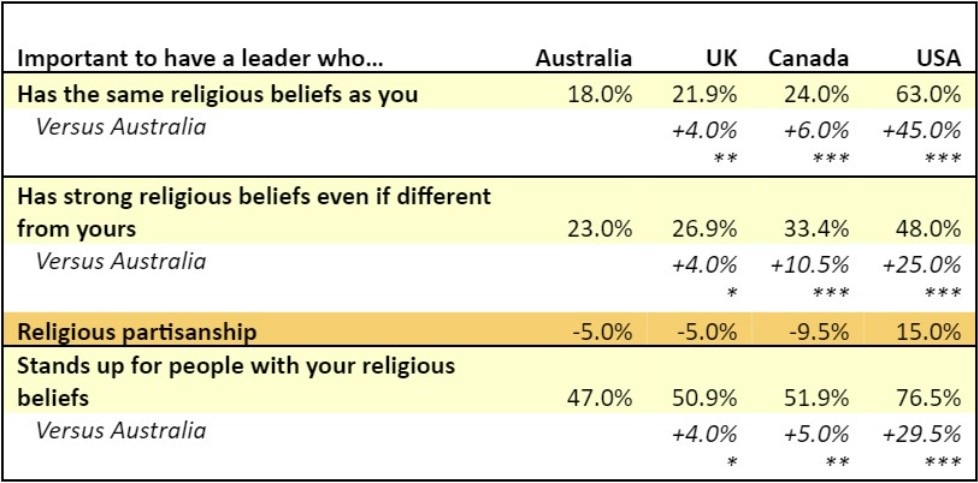

For all three questions, Australians were significantly less likely than citizens of each of the other countries to rate these things as important – 18 per cent, 23 per cent and 47 per cent respectively (see Table 1 below). It’s understandable that the third question, about general political representation, returns a much higher incidence of importance.

The most different country is the United States, highlighting its current struggle with aggressive religious partisanship. More than three times more Americans (63 per cent) than Australians (18 per cent) say their leader should have the same religion as them.

Further, while Australians, Brits and Canadians were each more likely to value a leader with religious views, even if different from their own, than a leader with the same religious views, the opposite was true for the United States. Partisanship on steroids.

The pointy end of the political stick

But, in terms of political science, the aggregated “important” measure (which Pew focuses on) tends to overstate real-world relevance.

What matters is the “very important” measure. That’s where opinion is most likely to convert into action. And for the first two questions in Australia, these are just 6 per cent and 7 per cent respectively.

This ties in well with other findings. For example, as I report in volume 3 of my five-volume Religiosity in Australia series, a tiny 5 per cent of Australians say that religion has a significant influence on their voting intentions. A whopping 86 per cent say it doesn’t affect their vote at all.

It’s no surprise then that the specifically religious political party, Australian Conservatives, established by former Liberal Senator Cory Bernardi, failed to get any of its candidates elected to parliament. Worse, it lost two MPs amongst its founding membership. In just two years, it was plain to see there was no public appetite for a “traditional Christian” party in Australia, and it was voluntarily deregistered.

A chilling underbelly of religious dominionists

I also report in volume 5 of Religiosity in Australia that 3.9 per cent of Australian adults are religious dominionists. Those are people who both say that their religion is the only acceptable one, and that religious authorities ought to be the final arbiters of law.

That’s about 770,000 Australian adults who believe their own clerics ought to head our legal systems. The belief correlates strongly and positively with both personal importance of religion, and with hard-right political orientation.

The figure of 3.9 per cent suggests that around two-thirds of the 6 per cent of Australians who think the nation’s political leader ought to have the same religious beliefs as themselves are religious dominionists.

It exposes a chilling underbelly of Australians who reject democratic representation and the separation of church and state.

In conclusion

This latest Pew research adds to our understanding of attitudes towards religion and religiosity in the political sphere. It shows Australians to be significantly less ‘religiously political’ than citizens of the UK, Canada and the US, and is consistent with previous findings.

Religious Australians often create an impression of the political importance of religion, but these new findings confirm most Australians don’t link religion and politics. Add to that the very short life of the Australian Conservatives party, the significant and continuing rise in the numbers of Australians who have no religion (already a larger group than Catholics and soon likely to be larger than all Christians), and the majority (69 per cent) – as outlined in volume 2 of Religiosity in Australia – who don’t trust the churches.

It’s important in a robust democracy to respect and accommodate the right to a range of non-violent and non-discriminatory religious beliefs and views. But the numbers are in. It would be a courageous politician indeed who advocated special privileges for one or other religion, or even religion in general.

Foolhardy, even.

Table 1: Prevalence of ‘important’ rating amongst English-speaking countries. Chi square significance (p): * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.0001. Note: ‘religious partisanship’ refers to having the same religious beliefs minus having strong religious beliefs even if different. Statistics are calculated using cell n counts back-calculated from total n’s and prevalence percentages presented in the report tables. Don’t know/refused to answer were excluded from analysis. Figures will be very close to but may not exactly replicate raw data analysis.

Published 11 September 2024.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Images: Melody Ayres-Griffiths on Unsplash (CC).