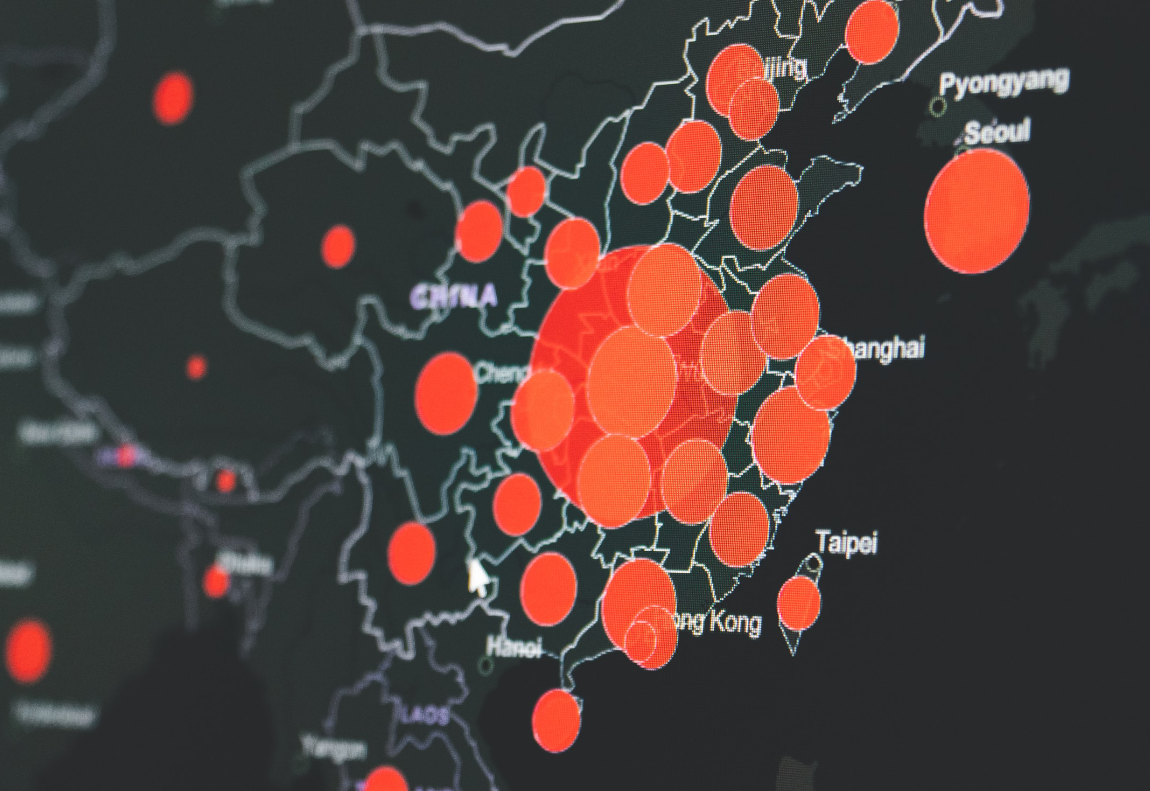

It started with a tweet. On 14 January 2020, as the world waited anxiously for news about the emerging virus in Wuhan, the World Health Organization published a tweet stating: “Preliminary Investigations conducted by Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus identified in Wuhan, China”.

As we now know, they were wrong. Very wrong. And, from all reports, many in China already knew they were wrong.

The culpability of the global health authority is mitigated by the probability their source of information, the Chinese authorities, was not reliable. But it set the tone for a pandemic that has routinely seen the affirmations and predictions of our academic class proven embarrassingly well off the mark.

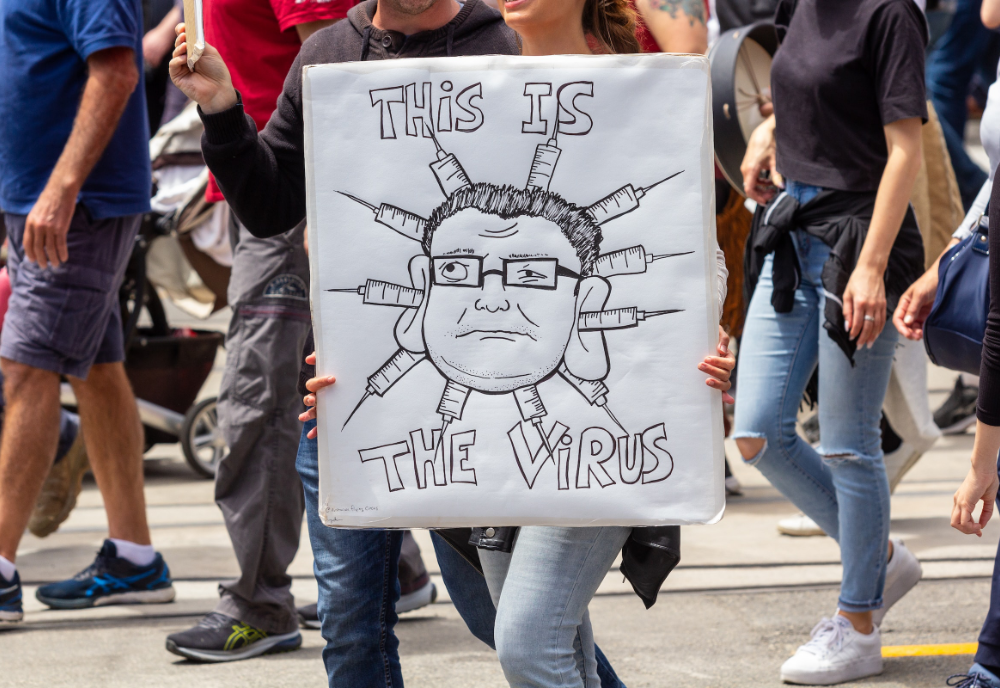

At first, US Chief Medical Advisor Anthony Fauci may have wanted to avoid a panicked exhaustion of already scant medical supplies. But the unfortunate reality that the most visible infectious diseases expert originally advised the American public “there’s no need to be walking around wearing a mask” creates yet more fodder to those that want to point out the fragility of scientific consensus.

Closer to home, the litany of hyperbolic modelling that consistently foretold of a Covid disaster that never seemed to eventuate has prompted many to doubt the value we place on the voices of experts.

The issue is exacerbated by the proclivity of the media to be attracted to the expert that offers the most sensational headline, allowing only a handful of the most media hungry to occupy a disproportionate quantity of the social discourse with the most extreme predictions and warnings.

So what damage has this done to a society that is still to confront the threat that remains the most significant existential threat of our generation – climate change?

Climate science is an impossibly complex field that most of us lay people have no realistic possibility of ever fully understanding. We can experience and comprehend the subtle changes that result from its mechanisations, but we are ultimately compelled to surrender our own inquiring minds to the assurances of the academics who have committed their lives to its study.

For the most part, as a society we have broadly promised them our trust. Most of us accept that climate change is real and that human activity is causing it. The first part is perhaps easier to observe for the scientific simpleton like myself through something as basic as a time-lapse photograph of a glacier. The second part, however, requires me to accept that I am not qualified to understand the scientific processes that make it true, and then accept that the scientific consensus is reliable.

So has 24 months of scientific missteps broken the public’s trust in the scientific consensus? Well … I hope not. Because we need that trust more than ever.

The differences between the scientific discourse around Covid-19 and climate change need to be made clear.

For starters, what has been consistent throughout this pandemic is the almost complete lack of consistency in our expert advice. Part of this is due to the fact that pandemics have a distinctly human aspect that climate science doesn’t. While a climate scientist can predict the result of a chemical reaction with utmost certainty, the endeavour of predicting human reactions, movements and compliance is unavoidably impacted by personal biases.

… what has been consistent throughout this pandemic is the almost complete lack of consistency in our expert advice. Part of this is due to the fact that pandemics have a distinctly human aspect that climate science doesn’t.

The responses of governments, even among wealthy and well-educated OECD countries, varied so significantly because of the social and political differences that altered the nature of their expert advice.

Within our domestic conversations regarding lockdowns, border rules and mask wearing, our experts were rarely disputing the scientific principles. Instead, they were questioning the human impacts of each policy.

Even their predictions for where case numbers would land were usually the result of their understanding of the unknown variable of human behaviour.

It must be remembered that, unlike epidemiology, the dissenting voices of climate science are not two sides of the same coin ultimately seeking the same objective. They are fringe and, generally, scientific outcasts. There is a consistent scientific consensus regarding anthropogenic climate change that has never existed in the realm of epidemiology.

There is no chemical equation that can predict human compliance with mask mandates or the social cost of lockdowns. Epidemiologists are not just being asked to interpret data; they are too often being asked to suggest policies that should have been equally contributed to by ethicists, sociologists and mental health experts.

Humans are not mere chemical compounds and are not bound by scientific laws that determine how they will behave. Yet, in a pandemic, our behaviour is one of the most crucial elements that determines our fate.

The understandable inability of the scientific community to form any real scientific consensus on human behaviour throughout the pandemic has been its greatest hurdle, and it is a hurdle it never cleared.

As a society, our task to convince the majority of the voting public of the urgent necessity to trust climate science, even if we don’t understand it, has unquestionably been made more difficult as a result of the inconsistent advice and modeling failures from our scientific community throughout the pandemic.

The reasons we must still trust climate science, its modelling and its warnings, despite the visible failures within epidemiology, will require yet more nuance and patience in the frustrating conversations we must continue to have with the unconvinced.

But climate science is different. The consequences of ignoring its warnings are more catastrophic than the most dire warning we ever received about Covid-19, and the international scientific community is speaking confidently with one voice. We must continue to listen.

This article was originally published on the author’s blog. It has been re-published with his permission.

Photo by Martin Sanchez on Unsplash.