The New Testament (Matthew 11:29) describes the relationship we have – or should have – with Jesus as a kind of work. “Take my yoke upon you and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls.”

As such, the Roman Catholic Church called for people to pray, and it organised religious marches, pleading to God to stop the 1660s pestilence – or the bubonic plague. The furtherance of the church’s purpose saw a deep religiosity persist even as the plague ravaged a largely Christian Europe.

Regardless of how and why God supposedly caused the plague, most medical theorists believed the plague was caused by bad air, or miasma. Both Hippocrates and Galen stated that bad air caused pestilence. The Arabs also accepted this theory, so it was the most orthodox model available to European physicians.

The failure of medieval medicine was largely due to the strict adherence to ancient authorities and the reluctance to change the model of physiology and disease the ancients presented.

People reacted with hopeful cures based on religious belief, folklore, and superstition largely informed by Catholic Christianity in the West and Islam in the Near East. These responses took many forms but, overall, did nothing to stop the spread of the disease or save those who had been infected.

The recorded responses to the outbreak come primarily from Christian and Muslim writers since many works by European Jews – and many of the people themselves – were burned by Christians who blamed them for the plague. Among these works may have been treatises on the plague.

But the plague also marked the beginning or, at the very least, an acceleration of a huge economic and sociological shift in Europe. Whilst it took some 200 years for population levels to recover, the medieval system of serfdom collapsed because labour was more valuable when there were fewer laborers – a phenomenon similarly observed as we emerge, in 2023, from our own pandemic.

Despite the dearth of workers, there was more land, more food, and more money for ordinary people living in the post-pandemic Middle Ages – a situation that didn’t last.

Recent bio-archaeological work using a broad sweep of medieval society shows that despite repeated plague outbreaks and other episodes of crisis mortality, the general population enjoyed a period of at least 200 years during which mortality reduced and overall survival improved compared to conditions before and during the plague.

Medicine, especially in Europe, also improved, with doctors increasingly questioning the efficacy of Galenic medicine.

David Herlihy in his 1997 book The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, tells how the plague pushed medical knowledge forward. The way the human body was studied changed notably. Medicine became a process that dealt more directly with the human body in varied states of sickness and health.

This said, drugs with a selective toxicity against pathogens weren’t available until 1911 when Arsphenamine was used to treat syphilis, 350 years after the peak of the plague.

The 1918 influenza pandemic

By the time the 1918 influenza pandemic broke in Europe and in the United States, the relevance of masks – at least for protecting medical workers and patients – and social distancing had been well established. By then, advances in public health policy ushered a newfound enthusiasm for political solutions, planning and collective action, not least of which was the prosecution of questionable assumptions about diseases and their causes.

At the same time, early versions of neo-positivism, a movement in early 20th-century American sociology which blended together the three themes of quantification, behaviourism, and positivist epistemology, began to gain popularity. It influenced how the 1918 pandemic was conceived and handled.

Given that its central thesis was the verification principle, the movement helped prompt researchers to distinguish, amongst other things, facts about the pandemic from unjustified opinion. From that grew the acceptance that events of the past are better described as fruits of past decisions, and our options for responses can be found in the work of those of our more recent irreligious predecessors.

But a willingness to acknowledge the achievements of recent predecessors is never a guarantee – at least not when eager egos are vying for prestige and prizes in a game of high-stake science.

In the 1910s, consensuses correctly supposed the “disease agent” was too small to filter out of bacterial solution. Not being able to view these agents, debate ensued about whether they were chemicals or very small organisms – a period wasted on philosophical disquisition, especially given Edward Jenner had developed the smallpox vaccine over 100 years before the Spanish influenza broke.

In an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine, David Jones, a Harvard professor of the culture of medicine, appraised such situations with a sober warning: “The history of epidemics offers considerable advice, but only if people know the history and respond with wisdom.”

While the 1918 H1N1 virus has been synthesised and evaluated, the properties that made it so devastating are still not fully understood. With no vaccine to protect against the virus and no antibiotics to treat secondary infections, treatment in 1918 included blood transfusion, a procedure that was not without risk.

Transfusion methods were rudimentary, performed directly from donor to patient, and blood typing and matching was in its infancy. Control efforts worldwide were, like in previous pandemics, generally limited to non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of disinfectants, and limitations of public gatherings.

Even so, both the 1848 and 1889 influenza pandemics took place at a time – and place – when more prosperous nations had created active health instrumentalities and systems of vital statistics. These pandemics were the first to be studied using the methods of modern pathology and bacteriology.

The German medical researcher Otto Leichtenstern published the definitive scientific study of influenza in Hermann Northnagel’s multi-volume handbook of special pathology in 1895, thus setting the standards against which medical authorities would judge their observations and conclusions during subsequent pandemics.

COVID-19

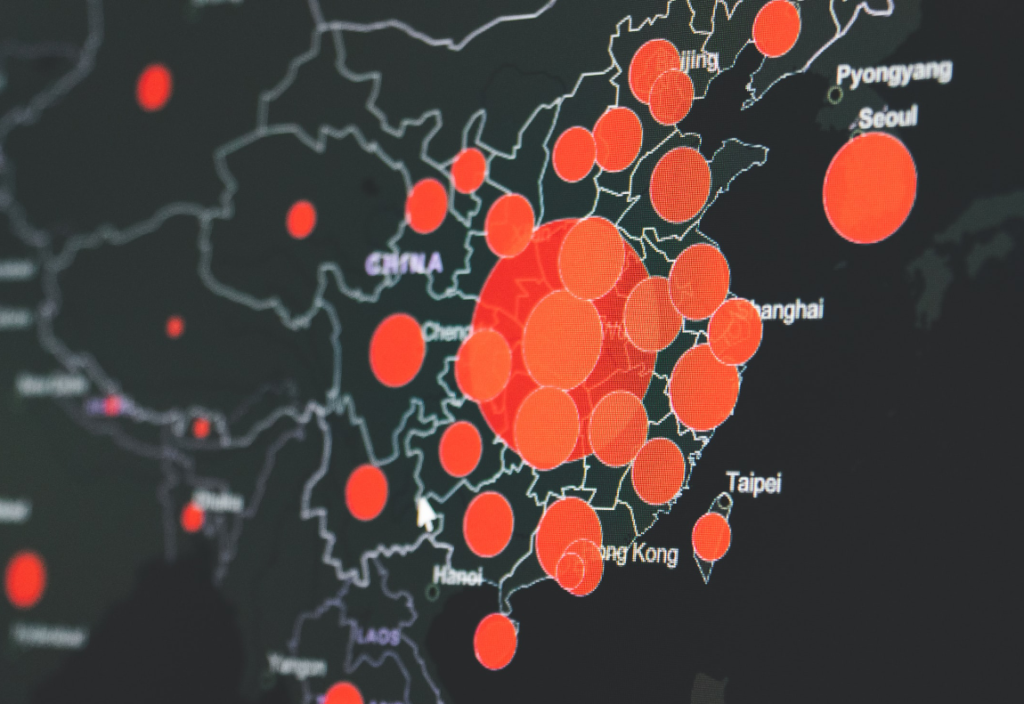

Having claimed about 6.6 million lives, there are signs the COVID-19 pandemic may finally be coming to an end. But any statement regarding an end of a major pandemic is as much a political construct as it is a public health opinion.

The Spanish influenza technically ended around April 1920, but the disease continued to run its course in some countries years longer than others. The 1918 strain never disappeared; rather, it continued to mutate, and a version of it continues to circulate to this day.

In May this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared an end of COVID. But since COVID infections have a high number of asymptomatic transmitters, we may not fully understand how societal, environmental and medical responses will affect the ability of the virus to evolve in coming years.

What we do know is that, as we gradually leave COVID behind us, we are not returning to the same ‘normal’ we once had. We’re certainly not seeing a ‘roaring 20s’ scenario ahead of us – at least not in Australia.

That said, the positive psychologist in me hopes that we might enter a kinder, more tolerant and stronger version of ourselves. As we recover, we might develop a new understanding of ourselves, have a new appreciation of life, undergo a spiritual change, become enablers, or see new possibilities in life.

There is an ancient Japanese art of fixing cracked pottery called Kintsugi. Instead of hiding the cracks, the focus is on rejoining the broken pieces with lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. When put back together, the whole piece of pottery looks beautiful again, even with the cracks that reveal its history – an analogy in the making.

My take on post-COVID healing may be rooted in a laundry list of banalities couched in pollyanna-ish optimism. But when it comes to how rapidly and successfully first AstraZeneca and then Pfizer, Moderna, and Novavax rolled out their multi-valent vaccines in Australia, it requires no embellishment. China, too, approved its CanSino vaccine for emergency use in high-risk occupations relatively quickly. And Russia announced the approval of its Sputnik V vaccine for emergency use in August 2020, less than 10 months after the virus was identified.

My take on post-COVID healing may be rooted in a laundry list of banalities couched in pollyanna-ish optimism.

Before this pandemic, the mumps vaccine held the record for shortest time to market. Just four years after 5-year-old Jeryl Lynn woke with puffy cheeks and a tender swollen jaw one night in 1963, her father, Maurice Hilleman, then head of pharma company Merck’s vaccine and virus research division, helped develop Mumpsvax, a vaccine to treat the mostly childhood disease mumps.

The captivating tale of Hilleman’s record-breaking development of the vaccine has all the elements of a mid-century American success story. But development of Mumpsvax didn’t actually start on that fateful night. Its development leaned heavily on groundwork that had been established during World War II.

One of the chief obstacles for developing the vaccine was growing large amounts of the target virus. In 1945, two American research teams made the simultaneous discovery that the mumps virus could be grown in specifically fertilised embryonic chicken eggs – a technique later used by Hilleman and his team.

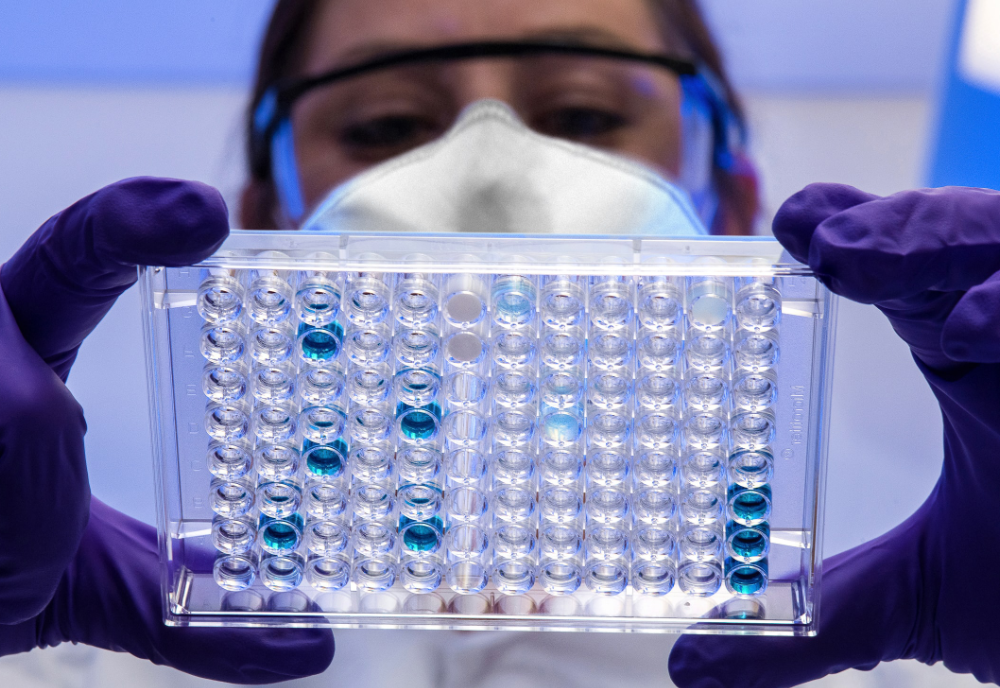

Even though the development of a COVID vaccine was considered as the unequivocal key factor that could completely resolve the COVID pandemic, much was made of the speed in which the vaccines were developed.

Whilst a great deal of early vaccine hesitancy is a reaction to the growing spread of misinformation, disinformation, conspiracy theories and rumours, a key determinant of hesitancy, according to the WHO, is also influenced by the level of confidence the public have in the product. Such confidence is best established through credible testimonials when longitudinal studies or multi-year trials were not available.

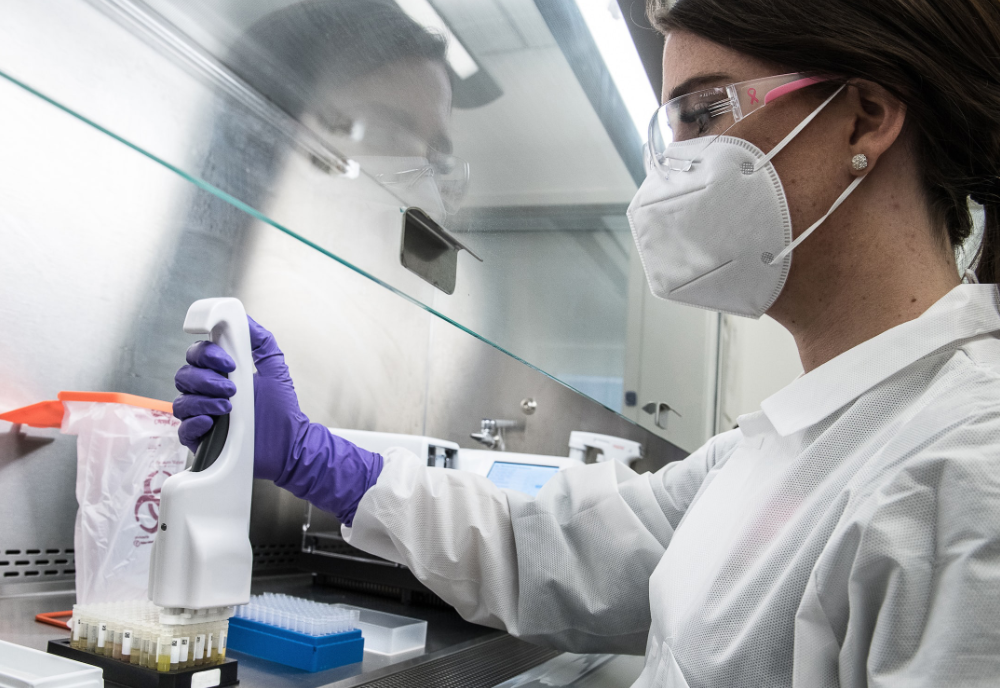

The Pfizer vaccine became the first to receive emergency-use authorisation from the American Food and Drug Administration just one year after the SARS-CoV-2 virus was first identified. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were the first mRNA vaccines that humans received outside of normally lengthy clinical trials.

However, like the mumps vaccine before it, big pharma didn’t start from scratch. According to the National Institute of Allergy there are hundreds of coronaviruses, including four that can cause the common cold, and those that sparked the ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome’ epidemic in 2002 and the emergence of the Middle East respiratory syndrome in 2012. In fact, we’ve been studying coronaviruses for more than 50 years.

Under normal circumstances, making a vaccine can take up to 10-15 years. However, amid a global pandemic, researchers quickly mobilised to share their data with others across the world.

Other factors facilitated this seemingly rapid development, including advances in genomic sequencing that provided researchers a platform to successfully uncover the viral sequence of SARS-CoV-2 in January 2020 – just 10 days after the first reported pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China.

This would not have been possible without adequate funding. Funding from sources ranging from the government to the private sector was critical in making the COVID-19 vaccine.

The European Commission alone has funded several vaccine candidates and worked with others, pledging $8 billion for COVID research. Australia’s 2021-22 Budget committed an additional $41 billion in direct economic support. As of May 2021, this brought the total support since the beginning of the pandemic to $291 billion.

COVID might have been one of the most universally shared moments in recent history, but that collective experience was instantly refracted into billions of entirely unique memories. It was a mesh of contradictions – the cheerful banging of pans in a home kitchen during lockdown mingling with the distant screeches of ambulance sirens.

The pre-pandemic era feels both a long time ago and yesterday. As we emerge from this pandemic, everything seems both totally different and kind of all-the-same.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Maksym Kaharlytskyi on Unsplash.