Australians preparing to vote in the Indigenous Voice referendum are facing a barrage of conspiracy theories: baseless allegations that the Voice involves reparations, land seizures, the United Nations and claims of ‘apartheid’.

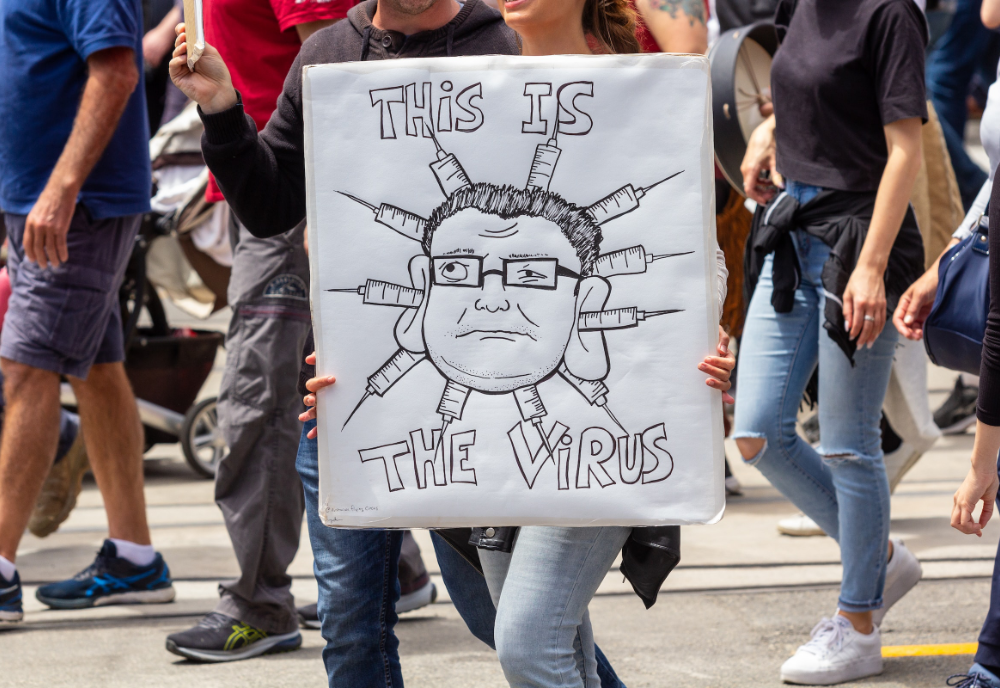

The degree and spread of disinformation ahead of the 14 October vote is similar to that experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic: most Australians knew, or knew of, someone who was radicalised into believing conspiracy theories about the virus, lockdowns or vaccines.

Despite the vast differences between the pandemic and the referendum, the playbook used by disinformation merchants is strikingly similar. This kind of overlap is common.

Endorsements of conspiracy theories are correlated. If you endorse one conspiracy theory, you are more likely to endorse another, even if the two have little in common.

This is partly explained by psychological reactance, a sensitive and angry response to perceived infringements on personal autonomy. This theory underpins why some people, when explicitly told not to do something, feel more compelled to do it.

A second related factor is feeling a loss of control. Psychological reactance and the feeling of losing control work together, because people more sensitive to infringements on autonomy are more likely to feel they’re losing control of their lives.

The COVID lockdowns were a source of autonomy infringements. There was a correlation between those high in trait reactance and those opposed to lockdowns, perhaps because that subset prioritised personal autonomy over public health.

For many in this position, engaging with conspiracy theories seemed to help regain a sense of control. In the QAnon conspiracy, believers see themselves both as persecuted victims losing their place in the world and heroes fighting back against elites.

Feeding this is a distrust of societal institutions. The former school principal who shot two police officers in Queensland in December 2022 was a prime target for disinformation after becoming unwell and losing his career within a public institution.

He experienced the powerful combination of distrust and a sense of losing control over his life that made him more vulnerable to conspiracies.

Disinformation campaigns stoke a distrust of institutions partly because they protects their cause from efforts by those very institutions to correct their lies. If the source of correction is undermined to the point it is not trusted, no amount of evidence is likely to convince a conspiracy theorist.

Australia seemed to be relatively unaffected by COVID conspiracy theories. Although its biggest cities saw anti-lockdown protests, apparent levels of compliance with rules and the initial high vaccination rate suggests conspiracies had a limited effect.

But disinformation may be affecting the Voice referendum. As false information started entering the mainstream, support for the ‘No’ vote went up.

Fake news spreads on social media faster than real news. Real news can often be procedural, dull and slow moving. Fake news tends to be the opposite: when someone fabricates a story, they tend to make it interesting.

The Voice referendum is procedural in the sense that it does not grant specific powers. It’s more attention-grabbing when someone claims this body will have veto powers over parliament, even though it won’t have such power.

A major part of the disinformation focuses on how much more power the Voice will have or how great its consequences will be — such as economic or land reparations — than what the proposal actually contains and the real likely consequences.

Disinformation campaigns stoke a distrust of institutions partly because they protects their cause from efforts by those very institutions to correct their lies.

The disinformation effectively implies non-Indigenous people and government bodies will lose their power and status, politically, socially and economically.

Social identity and status are intertwined in our social order. The disinformation campaign about the Voice alleges it is a threat to our social order and the positions of all non-Indigenous people in society.

It’s particularly threatening for people who see the economy as a zero-sum game. If someone else wins, they lose. When someone’s social identity and status is threatened, they stop thinking rationally and are more prone to twisting the information they have to fit prior assumptions.

Some approaches to combating disinformation focus on individuals at the point they decide to share a social media post, such as requiring users to privately endorse a post as true before posting to reduce the sharing of false information.

Another strategy is known as ‘prebunking”’, or debunking before exposure, where there are attempts to warn people about fake news before they are exposed to it, focusing on the motivation to manipulate that false information.

However, these strategies neglect the deeper psychological drivers that make some susceptible to misinformation.

People who have lost a sense of control in their life or trust in societal institutions often benefit from being empathically listened to. Having loved ones, and in some cases professional help, assisting can help people regain their sense of self.

The starting point to helping anyone buying into disinformation is presenting counter-evidence because some are simply misinformed. If that fails, understanding what they find threatening might help light the path forward — if they don’t believe the evidence, it might be because they feel their social identity and social status is under threat.

Sometimes, even an informed and empathetic approach isn’t enough. Stronger interventions to stop disinformation at the source, rather than just convincing people to not believe it, might have more impact.

Analysing patterns of fake news spread can help target where to shut the pipeline.

Social media platforms have eluded regulators under the guise of free speech, but free speech doesn’t mean unlimited reach on a global platform.

The starting point to helping anyone buying into disinformation is presenting counter-evidence because some are simply misinformed.

Committing to regulating social media is not the same as doing it effectively. The public would benefit from having ways to cut off disinformation and unreliable sources, as long as it doesn’t censor political speech that defies popular or government narratives.

There are proposals to regulate social media in multiple ways, such as requiring more rigorous content moderation and having more transparency around political posts that are paid to be spread. Others have pointed out that proposals for new disinformation regulation should include news media companies, in addition to social media.

However, it’s not yet clear how to properly incentivize or penalise media companies effectively to prevent them from enabling the spread of disinformation. Complicating the issue is if elected politicians directly spread disinformation to their supporters.

It would still help if there was more transparency around how these platforms work. Knowing how and why algorithms sometimes boost disinformation might help people come up with a solution. Many experts are focusing on how spreaders of disinformation take advantage of vulnerabilities in social media’s designs.

The goal of disinformation campaigns is to prevent rational debate. When an issue of national consequence like the Voice referendum arises, having space for clear, thoughtful discussion is important for a functioning democracy.

The forces behind disinformation do not want different social groups to establish a common ground. Instead they want distrust and for every group to see every other as a threat. For example, disinformation that reduces the certainty of climate science results in less cooperation, and more self-interested actions that do not prevent climate change.

So, until those spreading harmful disinformation are held to account, it will be tough to rebuild societal trust.

This article was originally published on 360. It is republished under Creative Commons.

Photo by DJ Paine on Unsplash.