As a medical student at the time that I voted ‘Yes’ in the 1967 referendum, it was a ‘no-brainer’ to accept the Aboriginal people into full Australian citizenship, and provide them with rights and obligations.

The ability of the Commonwealth to take oversight of Aboriginal affairs and make laws, such as to establish a Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs, was initially, I thought, to protect Aboriginal people from the rampages of the states, such as Queensland. That was based on my experience of coming to Queensland and working in Aboriginal health from 1979 to 1991.

It was the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA) who protected us at the Aboriginal Health Program (AHP), and our very effective community programs, from our own employer, Queensland’s health department. See Rosalind Kidd’s The Way We Civilise for a journalist’s ‘outside’ view on this period and the lead up to it.

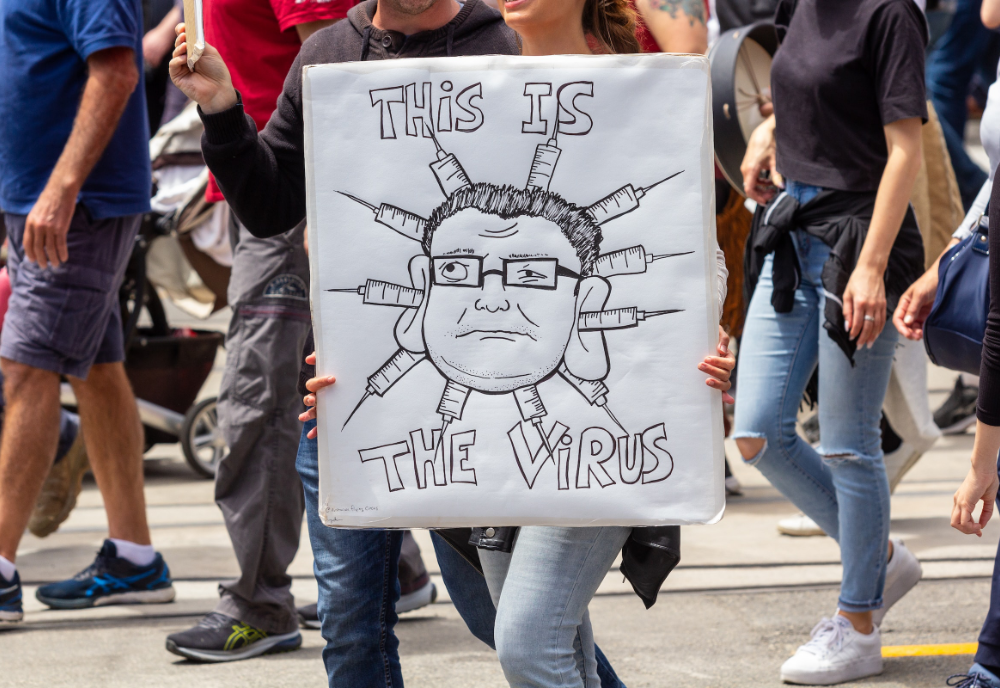

Earlier this week, one of my neighbours erected on their property a large standard-issue ‘Yes’ poster in support of the Voice. The whole ‘Yes’/’No’ campaign reminds me of how I felt in the late 1960s to the early 1970s when Australia was actively involved in the Vietnam War. Any nay-sayers were branded as communist traitors and often beaten up at peaceful protest demonstrations. And that wasn’t even about a referendum.

Once I graduated in medicine from University of Sydney at the end of 1972 – and even though I had voted for the Whitlam Labor government – I high-tailed it across to the mountains of New Zealand. One of my extreme Right-wing fellow students, who was also a pharmacist, berated me for abandoning Australia to Labor.

As it was with the issue of the Vietnam War, the coverage of the Voice in my main sources of news – ABC and The Guardian – are around 95 per cent in favour. Several days before the ‘Yes’ sign went up in my street, ABC published an article that featured Dr Jason King of the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) General Practice in Yarrabah. All dressed up in the bright and breezy Aboriginal patterns and colours like a football club fan, he encouraged everyone to vote ‘Yes’ to the Voice because it would be a way to get rid of rheumatic fever in Aboriginal communities.

Within a couple of days, prominent ‘Yes’ campaign leader Noel Pearson also made the same claim at the National Press Conference in Canberra.

During the years 1979 to 1991, I worked as Regional Medical Officer (Northern Region) in the AHP in Cairns, and worked with 14 AHP teams throughout Cape York and the Torres Strait. Each team was made up of a specially trained public health nurse and several local Aboriginal or Islander health workers. The teams were able to achieve a lot working closely with communities such as Yarrabah and with their elected Community Aboriginal Councils. But, in July 1991, the AHP was closed down due to withdrawal of federal funding to the state.

Besides monitoring the growth-and-development of children and vaccinations, and assisting with antenatal and postnatal care, adult health, and health promotion, the AHP team and the community of Yarrabah had significant nationally relevant success with at least three programs.

The first was in the early 1980s and resulted in a nation-wide free hepatitis B vaccination for all Aboriginal pregnant mothers, and all newborn Aboriginal babies since. This came from a small study I did with Yarrabah patients demonstrating clearly that the main method of transmission of the Hepatitis B virus in an Aboriginal community was vertical, passed from mother to infant during the birthing process, or shortly afterwards.

In the late 1980s, the AHP team, working with men and women with type 2 diabetes in Yarrabah, won the national Boehringer Ingelheim Prize for Excellence in Diabetes Management two years running. That was a significant feat, given the team was competing with every other diabetes management group in the country. Having received blood glucose monitoring machines through the competition, we were able to have our diabetic patients doing blood glucose monitoring with their own machines.

The third achievement was related to rheumatic fever/carditis. In the mid 1980s, a young Yarrabah mother died in Cairns Base Hospital from heart failure during the delivery of her first baby. The failure was the classic story of hidden heart valve damage due to attacks of rheumatic fever during childhood.

The whole Yarrabah community was devastated. The young woman was the daughter of one of the members of the community elected to Yarrabah Aboriginal Council, and my resident AHP health team had been working closely with the council for many years.

The whole ‘Yes’/’No’ campaign reminds me of how I felt in the late 1960s to the early 1970s when Australia was actively involved in the Vietnam War. Any nay-sayers were branded as communist traitors and often beaten up at peaceful protest demonstrations.

In an extraordinary coincidence of timing, I had just been reading an article in The Bulletin of the World Health Organization by an Arizona-based cardiologist working with the Indian Health Services. Their laboratory had developed a rapid identification kit to detect the specific bacterium in the complex chain of causation for acute rheumatic fever/carditis (ARF/C), namely the beta Haemolytic Streptococcus Group A.

The Indian Health Workers had developed a program of throat swabbing children – the most at-risk group – and on-the-spot treatment of any child with a positive swab with one intramuscular injection of a slow-release penicillin. The justification was that such children were not only in danger of ARF/C themselves but also, in the crowded living conditions of the Indian communities, a danger to others.

In 1985-6, the accepted ‘truth’ – still prevalent in some quarters today, apparently – was that the only way to get rid of ARF in a community was to wait for the seeping down of improved housing, hygiene, and decreased crowding. Those take culture change – and a lot of money for more housing.

So, in one stroke, the Indian Health Workers were showing us that we could sidestep having to change two of the causal elements for ARF/C and eliminate the initial causative organism itself – and very cheaply.

I personally took the idea to the Yarrabah Aboriginal Council. According to my research at that time, the community of Yarrabah had the highest rates of ARF in the world – at least that I could find in the literature. The council said unanimously: “Go ahead doctor, you have our full support.”

There was, however, a complication. The head doctor and nurse of the AHP in the head office in Brisbane actively inhibited – possibly for financial restrictions – the public health nurse and our team of Aboriginal health workers from working too closely with the Yarrabah Community Council.

The council had requested – probably on the legitimate and professional suggestion of the public health nurse – that they would like us to do a growth-and-development health screening of children from 0-15 years, and provide them with a report summary and recommendations for their planning services in the community. We did the screening quietly, with the full cooperation of the community. Instead of sending results to Brisbane for the official calculations and report, I did it myself and provided the report and recommendations to the council.

Hence, the ARF throat swabbing of school-aged children three times a year after holidays was kept low-key from the start, with quiet support from Cairns Base Hospital pathology/laboratory, and paediatrician. This program was carried on from early 1986 through to July 1991, when the Aboriginal Health Program was disbanded.

During those five and a half years, we had no cases of ARF in that community. When a cardiologist from Royal Brisbane Hospital did his annual visit to Yarrabah and other towns and communities around Cairns, following up on his ARF/C patients from earlier years, he praised the program. At his insistence, we wrote an article about the Yarrabah rheumatic fever prevention program and had it published in the Medical Journal of Australia.

So I find it frustrating to hear the current resident doctor in Yarrabah – of all places! – exclaiming to the world that voting ‘Yes’ at the referendum would be a way to rid the rheumatic fever problem from Aboriginal communities.

Another major reason touted for the establishment of a Voice to parliament is the need for Aboriginal communities to have better and more housing and services, such as reticulated water and sewerage systems, and food availability. There are, of course, far better, more rational, and more effective ways of getting improved housing and services.

In 1979, after two years working for the Papua New Guinea government health services, I joined the AHP and visited Aurukun on the Gulf coast of Cape York Peninsula, just south of Weipa. The community was a grouping of the 21 Wik clans living in small corrugated iron sheds with an outside stand-pipe as the only service facility for washing. I was appalled.

With assistance from state health inspectors, we designed an Environmental Health Survey (EHS) suitable for assessing Aboriginal communities. From then, we added the EHS report summaries to our standard health screening reports for children.

I personally handed these over to the elected community Aboriginal councils, with discussion and recommendations. The councils were able to jump the state and go directly to the federal DAA for funding. Through the 1980s, many houses were built, water and sewerage were reticulated, and food supplies improved. Child morbidity and mortality rates declined significantly.

In Queensland hospitals, if something goes wrong in the management of a patient a ‘Root Cause Analysis’ process is carried out. This is a thorough search of the causal linkages which led to the incident in question, rather than blindly accepting that the proximate obvious cause was the only one. This comes from industry’s ‘Five whys’ – the searching for why something occurred or failed in a process. This is how the health ‘gap’ needs to be closed in Aboriginal communities or any other disadvantaged groups in the country.

In some cases, when we follow the ‘whys’ back towards the violence and losses of colonial dispossession, there may well be mistakes, misunderstandings and cultural practices that can be remedied today. Such a process would ensure that we do not wait for improved housing and decreased overcrowding to prevent acute rheumatic fever, and that in a community with continued significant incidence we screen the most at risk for the causative organism.

Because of our political and bureaucratic incompetence in addressing the legitimate needs of all Australian citizens by fairly allocating resources to those in most need, the ‘Yes’ case for the Voice is proposing the enshrinement of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice lobby group in the constitution. I believe this would divide Australians into two tribes in perpetuity. This is anti-democratic and moves in the exact opposite direction to the intent of the successful ‘Yes’ vote attained in 1967.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by michael fontenot on Flickr (CC)