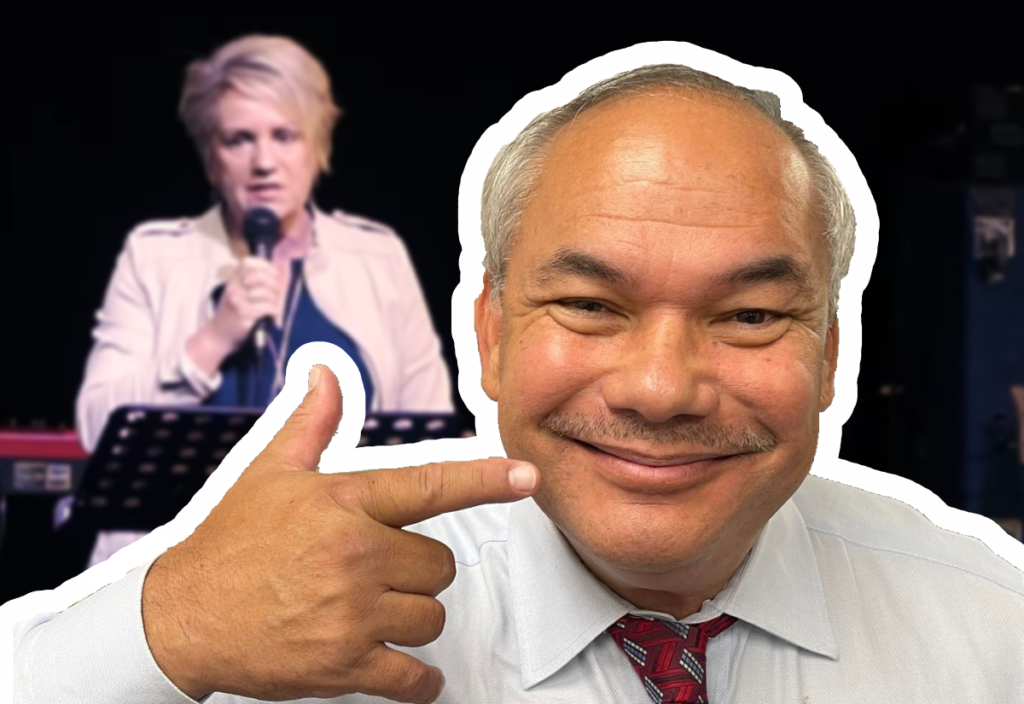

The “new face of Pentecostalism in Australia” was joyfully proclaimed in a recent edition of the Weekend Australian newspaper. “Rock star preacher, social media machine, 40,000 members,” the newspaper shouted. “Move over Hillsong, there’s a new Pentecostal brand in town,” it declared.

A lengthy magazine article by senior writer Greg Sheridan identified the new church as Kingdomcity and named its leader as Mark Varughese, 48, a handsome and charismatic Australian lawyer of Malaysian-Indian background.

Sheridan’s enthusiastic introduction of Kingdomcity and Mark Varughese is surprising. Sheridan is an intelligent Christian and impressive thinker who might have been expected to greet Varughese’s pitch with some caution. Not so. Sheridan is uncritically supportive of this latest manifestation of Pentecostalist hot-gospel worship.

He presents Varughese as the embodiment of positive changes in Pentecostalism since the scandals that have damaged the once-dominant Hillsong movement, following disclosures that the late father of former Hillsong leader Brian Houston was a predatory paedophile. Similar scandals have, of course, undermined the moral authority of many religious denominations in recent years.

While Sheridan notes that the Hillsong scandals “hurt the broad Pentecostal brand”, he says Varughese is a “different style of pastor” and writes that Pentecostalism is “becoming sturdier, putting on more intellectual muscle” and “achieving a depth of learning to match”.

These claims are, however, not deeply supported. But Sheridan’s main implication seems to be that Varughese’s Kingdomcity is a superior and more virtuous successor to the discredited Hillsong Pentecostal brand.

Another possibility not canvassed by Sheridan is that Kingdomcity is merely a rebranding and renaming of Hillsong under new leadership, promoting the same ideas and employing the same strategies of persuasion based on mass hysteria whipped up by amplified pop music. There remains the repetitious rhetoric of preachers skilled in the marketing and show-biz arts of drawing emotional responses from needy and suggestible audiences, and the extraction of large financial donations from them.

So is Kingdomcity perhaps attempting a takeover bid for the troubled Hillsong franchise and its followers?

There remains the repetitious rhetoric of preachers skilled in the marketing and show-biz arts of drawing emotional responses from needy and suggestible audiences…

This darker possibility is not canvassed by Sheridan. But it is certainly suggested by the American website The Kansas City Defender which reports: “Before Kingdomcity KC” – presumably Kansas City – “gained its current name, it was slowly integrated into the Hillsong network through partnered events, and later a complete renaming as Hillsong KC”.

Perhaps the decline of Hillsong is prompting its reverse renaming in Australia as Kingdomcity.

Whether this is so, there is really little new about Mark Varughese and Kingdomcity Pentecostalism. Like other similar and earlier groups, it deploys amplified rock-pop music, jumping and dancing singers, and repeated and emotional phrases about Jesus, blood and salvation that reduce some audience members to jabbering idiots who claim to “speak in tongues”. Sheridan’s article paints a powerful picture of these techniques at work in Kingdomcity.

This sort of emotional exploitation is a popular form of worship in some southern parts of the United States. Perhaps the most devastating account appears in the 1927 novel Elmer Gantry by the satirical novelist Sinclair Lewis. The novel was widely banned because it dared to suggest that Christian preachers could be corrupt hypocrites, conmen and grifters who manipulated vulnerable followers in their pursuit of personal wealth and power.

In the 1920s and 1930s, an evangelist and former baseball player named Billy Sunday attracted great crowds in the US with his hellfire and brimstone sermons. In the 1950s, the hot-gospelling Oklahoma evangelist Oral Roberts brought his tent show to Melbourne and was run out of town, complaining that he had lost 40 thousand pounds on the crusade.

In the 1960s, the somewhat smoother Billy Graham persuaded thousands to “come forward” and be saved at his crusades. In the 1980s, the US lived through the ascendancy of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker, whose PTL (Praise The Lord) franchise collapsed in scandal with Jim sent to gaol. It also endured Jimmy Swaggart, who was caught with a prostitute in his hotel room and bawled his eyes out on television.

More recently, the global Hillsong brand claimed to be saving the world until its dirty secrets were exposed.

There has been no suggestion that Varughese is in any way corrupt or hypocritical. But Pentecostal theology and strategy do not much change over time; the family resemblances are strong. It is essentially a revivalist movement that speaks of individuals being “born again” by accepting the Christian Holy Spirit into their lives.

Typically Pentecostal movements have leaders who ground their authority in claims of life-changing personal religious experiences. They are frequently adorned by attractive wives and families, and enjoy lives of luxurious affluence.

Pentecostal religious services resemble high-octane pop concerts with loud music, mass arm-waving, and lengthy monologues from preachers who transfix believers with claims or demonstrations of their faith-healing powers and the ability of the faithful to “speak in tongues” with messages from the Holy Spirit. The shows attract mass audiences in many parts of the world.

Pentecostalism is particularly focused on the fundraising needed to finance and to spread their expensive communications and performance technologies. Perhaps most controversially Pentecostalists preach “prosperity theology”, which assures followers that the more they give to the organisation, the more they will receive in return from God.

To outsiders, this might seem a regressive and deeply offensive notion that advantages the rich over the poor, but it plainly works to provide Pentecostal organisations with the funding they need to spread their message, build their cavernous theatre/temples, and allow leaders to live very well indeed.

Sheridan’s article touches lightly, even approvingly, on these aspects of Varughese and Kingdomcity. He recounts Varughese’s “burning bush moment”, his “encounter with God” and how, when about 12 years old, he fell to the floor of a church and spoke in tongues for about 45 minutes. Some might wonder whether this was a religious experience or a psychotic episode brought on by some emotional stress.

With his attractive wife Jemima, he claims to have built a multinational organisation with tens of thousands of adherents. Sheridan does not question the extent of Varughese’s personal wealth or Kingdomcity’s corporate wealth. Asked about prosperity theology, Varughese says little more than: “The error is always in the excess”. Some might say the error is in the idea itself.

A seven-word note at the bottom of the Australian article notes that Sheridan visited Varughese and Kingdomcity “as a guest of Kingdomcity”. So it seems he was an invited guest brought in to suggest that diseased Hillsong should “move over” and make way for healthy Kingdomcity. Perhaps it should. But don’t hold your breath waiting for the emergence of any new Pentecostalism.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Shaun Frankland on Unsplash.