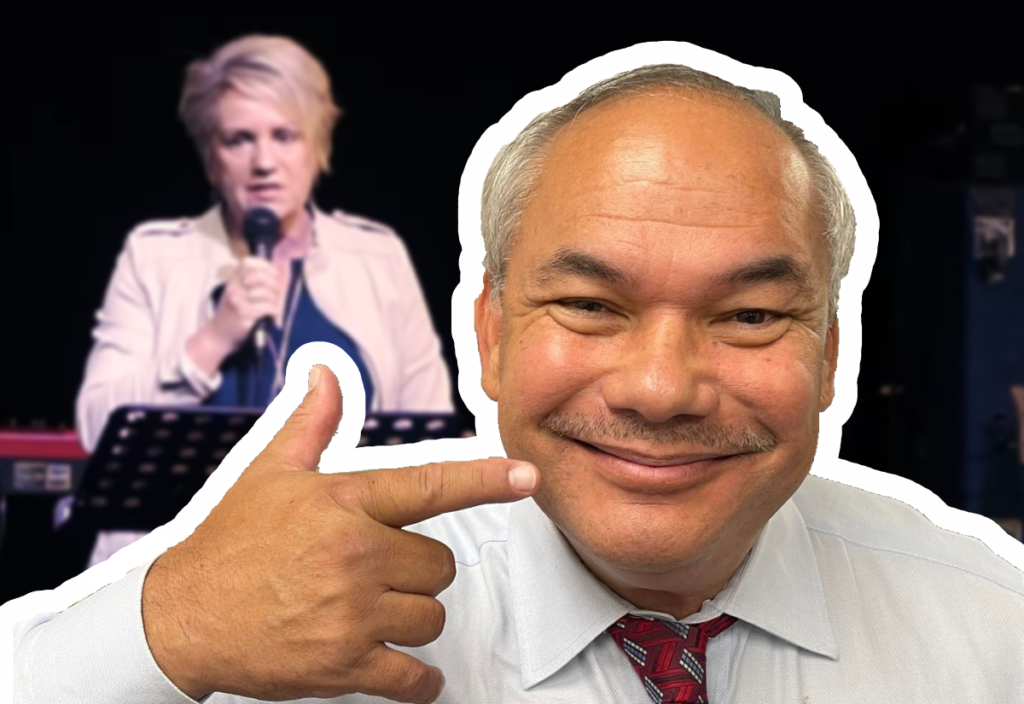

Attending the Religious Freedom roundtable in November 2015 on behalf of the Rationalist Society of Australia, I was bemused by the welcome speech given by the event’s sponsor, the Honorable Attorney-General George Brandis.

Entering in his dark suit, with his grave countenance, Brandis reminded me of the archetypical Cold War CIA director – the sort you might see in the Bourne series of films.

He began by noting how Catholics were now “routinely the subject of mockery and insult by prominent writers and commentators”, quoting Dyson Heydon who described it as “the racism of the intellectuals”.

“Or perhaps he should have said the pseudo-intellectuals,” said Brandis through gritted teeth.

Some religious Australians “felt increasingly unable to express their opinions or faith in the public square”. Public figures such as Tony Abbott were subject to “incessant, smearing ridicule”.

According to Brandis, the roundtable was about finding ways to ensure respect for those of faith. As a non-religious attendee, I found the speech remarkable in illustrating the stark difference in our perceptions of current events, and the very meaning of religious freedom.

We can hear these echoes in a piece Brandis contributed for the Sydney Morning Herald on Christmas Day, urging us to “spare a thought today for persecuted Christians”.

Brandis prefaces his remarks with a similar jeremiad against the alleged sneering of secularists towards his own faith.

“Catholicism – professed by one in five Australians – has been a particular target. Shamefully, much of that anti-Christian – and in particular anti-Catholic – bigotry has been encouraged by the national broadcaster in both its satirical programming and ‘investigative’ journalism.”

He moves on to quote Pew Research showing “Christians have been harassed in more countries than any other religious group”, mostly in the Middle East and North Africa, especially Coptic Christians in Egypt.

Clearly, Brandis seeks to connect criticism of Catholicism with real-world persecution of Christians.

“Religious intolerance begets religious persecution, identified by the UN as one of the world’s principal human rights challenges.”

The clear implication is that secular criticism of faith causes Christian persecution.

But alas, the high levels of Christian persecution worldwide are largely driven by religious intolerance in Muslim-governed countries – and dictatorship in North Korea. Thus, the problem is linked directly with totalitarianism, theocracy, and the absence of secularism – the persecutors are not sneering secularists; they are mostly faith-based governments.

Clearly, Brandis seeks to connect criticism of Catholicism with real-world persecution of Christians.

Brandis infers that criticism of faith amounts to persecution. It seems that Brandis identifies as a victim of Christian persecution by secularists. This is an obscene false equivalency, juxtaposing Christians who are imprisoned, tortured and executed for practising their beliefs, against well-heeled leaders and journalists forced to endure some mean comments about their faith.

It’s a refrain we’ve heard often from The Australian, Sky News, the Australian Christian Lobby, and many others, targeting Fairfax (now Nine) and the ABC, doing so repeatedly despite the apparent absence of unfair or egregious ridicule.

According to journalists Jonathan Homes and David Marr, criticism of the Catholic Church has been generally in relation to the Papal visit of 2008, the child sexual abuse scandal, and the various controversies surrounding George Pell.

But there is a backstory to their paranoia. The Christian persecution complex is a well-studied phenomenon, and another thing we appear to have imported from the US.

According to the academic Elizabeth Castelli, author of Persecution Complexes: Identity Politics and the ‘War on Christians’, the Christian persecution complex, as she explained in 2008:

“…mobilizes the language of religious persecution to shut down political debate and critique by characterizing any position not in alignment [with] this politicized version of Christianity as an example of antireligious bigotry and persecution. Moreover, it routinely deploys the archetypal figure of the martyr as a source of unquestioned religious and political authority.”

The narrative of persecution is common in US debates where traditional values clash with public policy. The Fox News ‘War on Christmas’ bemoans the secularisation of Christmas by retailers. Since the 1990s, the persecution narrative has been illustrated in numerous ways, including through the ‘Jesus Freak’ movement, the novel Left Behind, the God’s Not Dead movie franchise, the movie Persecution, the book God Less America, not to mention conservative punditry.

In The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom (2013), English academic and historian of Christianity, Candida Moss, describes the concept of ‘persecution’ as central to Christianity. Tracing stories of martyrdom from antiquity to the present, she explains how some modern Christians identify as victims – even whilst holding the majority or wielding significant power.

There’s certainly a sense of the martyr in Brandis’ rhetoric. It seems that the Christian persecution complex is both an indelible part of the Christian psyche, as well as a useful political tool.

The victim of the Christian persecution complex suffers for Christ. He is figuratively nailed to a cross, heroically enduring the slings and arrows of secular reason at the hands of Satan, sneering secularists, the ABC, and possibly even Human Rights Commissioners.

From a secular perspective, we can only highlight how the criticism of ideas and practices is in no way the same thing as actual persecution, but rather, a crucial requisite for open debate. Criticism and even ridicule are the necessary filters keeping democracies like ours strong, challenging the status quo, and encouraging new ideas. It’s something sadly lacking in those parts of the world where minorities are persecuted.

As we usher in a New Year, we should indeed spare a thought for persecuted Christians. We should spare a thought for all people who are persecuted – for women arrested in Iran for not wearing headscarves, for victims of slave labour, for those imprisoned for their political or religious views, for those punished because of their sexuality, and for the myriad others.

There are plenty of martyrs in the world. We should do more than spare a thought. We should think hard about the actual causes of persecution, as opposed to grinding a particular axe.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by CEBIT Australia (Flickr CC)