As I sat in my classrooms at Frenchs Forest Public, Chatswood Public and Forest High, dreaming about my future, I did not think that defending universal, free, secular, public education was what I’d spend my life doing. I took my excellent public education for granted as I mildly misbehaved and lollygagged at the back of my suburban classrooms.

Almost every kid living in the catchment attended those schools, whatever their father did (and it was generally fathers in the 1960s and ‘70s) or what god their family may or may not have believed in. We kids were all mixed in together, more interested in one another’s ‘cool’ quotient than in our class status or family income.

There was a large Housing Commission estate opposite my school. Many of my friends lived there. Did I give a damn? No. The rapidly expanding suburbs of Belrose, Davidson and, to a lesser extent, Terrey Hills – where my Managing Director father and stay-at-home mother built a house – were more aspirational.

My best friend lived in a bohemian household – it was tumbling down and always a mess – on an unsubdivided block. She and her sister had two horses! That was super-cool.

A few families were seriously religious. Some were Catholic, but most were nominal Church of England at best. A group of Muslim students arrived as refugees from Iran, and the girls were allowed to wear trousers because their religion banned them showing their legs. This meant we all could. It was a huge boon for our previously-frozen legs in winter.

Some of my school friends were affected by the wave of religiosity that followed Billy Graham’s visit to Australia in 1969. My nextdoor neighbour and I would have quite intense arguments about the Festival of Light, as we lugged our Globite school bags home from the bus. She was a convert. I was not. We remained good friends.

Anyone who went to St Pius or Our Lady of Dolours – the nearest Catholic schools – was regarded with pity. The boys had to keep their hair short and the girls their skirts long – death to a teenager’s ‘cool’ quotient in the 1970s. As an aside, ‘dolour’ literally means great sorrow or distress. Yet, some grim-faced nun decided it would make a great name for a school for girls. Bizarrely, it still exists, and is thriving! There’s no explaining the choices of some parents.

My schools were free in that they were paid for by the taxpayer and available to every local child of school age, regardless of how much money their parents may have had. That was a great leveller.

Far from meaning some better-off parents could ‘bludge’, it meant that all us kids were mixed in together, without the knowledge of whose parents were better off and whose weren’t.

Some of the students I shared classes with lived in the local caravan park, and there was a lot of semi-rural poverty in Terrey Hills and Duffys Forest at the time. As long as those kids were cool, we didn’t care if they lived in a leaking caravan or a neat-as-a-pin project home. One girl I knew slept in a converted bus.

Our school helped us to understand we were all of equal value. That’s because public schools believe that. They put students at the centre of what they do, because they gain their income via the funding allocated to each one. Fee-charging religious schools, by definition, must put parents at the centre, because that is who pays their bills.

Our school helped us to understand we were all of equal value. That’s because public schools believe that.

It is this inclusivity that demands public schools be secular, because prioritising any faith is an enrolment barrier. If you accept every child, you must create a community that is welcoming to every child.

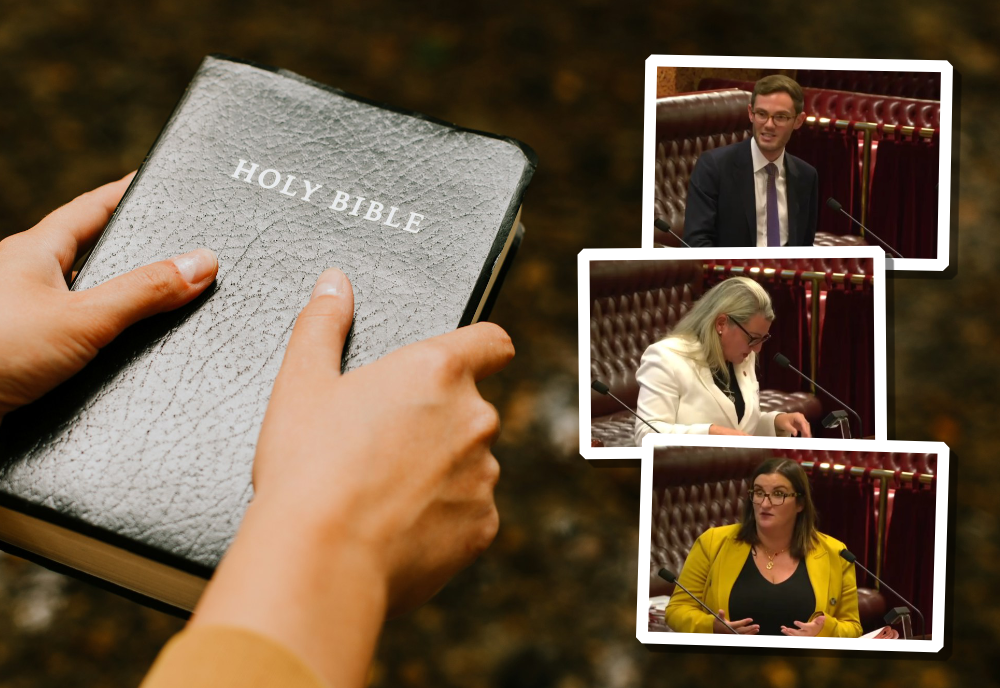

It is because of the core inclusivity of public schools that having chaplains in such schools – however nice and well-meaning – is an anathema. Worse, it is an insult. It represents the arrogance of those of a certain faith – in Australia’s case, Christianity – who regard any value that does not directly reflect their own world view as automatically inferior and suspect.

The chaplaincy program sneers at the great central virtue of public education: namely that it welcomes every child as an equally important member of the school community regardless of the kind of family they come from.

To my mind, the very concept of religious education is an oxymoron. Education is meant to teach children how to think, not what to think. If you do the latter, it is not education; it is indoctrination and certainly should not be publicly subsidised.

As the British philosopher Stephen Law pointed out in his book, The War for Children’s Minds, parents would rightly be shocked if there were ‘Labor schools’ or ‘Liberal schools’, or ‘communist schools’ or ‘capitalist schools’.

Why is it okay for there to be Catholic, Muslim or Protestant schools by that measure? After all, I would argue that there is no such thing as a Catholic, Protestant or Muslim child; only the child of Catholic, Protestant or Muslim parents. Surely, if religions have a compelling case, they do not need to compel belief, particularly among the young?

Teaching ethics and comparative religion is a great idea in publicly funded schools; proselytising for any particular deity is not. Not to mention the active harm such proselytising could do to children struggling with their gender, their sexual orientation or with an unwanted pregnancy.

I know that chaplains are not supposed to proselytise. But, pardon my scepticism, in that case why must their employment depend on them being religious? And, surely, anyone paid by the public purse to help children grapple with difficult, sometimes existential, questions should be trained and qualified?

If they are trained and suitably qualified, I don’t care if people who perform these roles have a personal religious faith or not. But they should be called school counsellors, not the very loaded ‘chaplain’.

Australia is a secular country. It supports and celebrates citizens of all faiths and none. Freedom of religion and freedom from religion are among our core values. Our public schools must reflect that.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo: South Australian History Network (Flickr CC)