This is an excerpt from Neil Francis’ soon-to-be published Part 2 of the Religiosity in Australia research series, commissioned by the Rationalist Society of Australia.

Recently, Australia’s most religious have been pressing the federal government to pursue legislation that would increase the rights of the religious.

The government is responding in kind with telling enthusiasm. A clear sign is that rather than dealing with a balance of rights and obligations amongst all Australians, religious or not — and which would properly be human rights legislation — the government’s bill for legislation is accommodatingly titled “Religious Discrimination Bill”.

This highly improper and unbalanced approach deserves greater national debate.

As former High Court justice Michael Kirby wrote in the foreword of Part 1 of this series: “The right to swing my arm stops when I hit someone else on the chin. My entitlement to religious liberty must be accommodated to the rights of others to be themselves.”

What religious conservatives intend happens between swinging arms and chins is handsomely illustrated by their political machinations on voluntary assisted dying (VAD), abortion, family planning, LGBTI staff and students, and other matters.

Religious conservatives are arguing that religious arms should have the right to swing with extensive freedom, and chins that those arms might contact can be lawfully demanded to withdraw themselves. Equally, the argument entails that non-religious swinging arms must be legally restricted, lest they connect with religious chins.

The proposed reforms wouldn’t grant balanced religious freedom, they would grant religious privilege. They wouldn’t act as a shield. Rather, they would act decisively as a sword. The irony is that furnishing the religious — especially institutions — with special privileges doesn’t serve even the nation’s most religious, the 11% who are Devouts. As illustrated in Part 1 of this series, many Devouts support abortion, VAD, and marriage equality. Similarly, a significant majority of Australian Catholics support abortion, VAD, and marriage equality. Catholic institutions banning the practices are an offence against the consciences even of their own flock.

Allowing religious institutions to unilaterally extinguish the real consciences of Australians, including Devouts and most of their own flocks, supposedly in their service and even on their own purse, is an unconscionable offence against Section 18 of the UN’s Declaration of Human Rights.

Is all this necessary? As Robyn Whittaker, Bromby Senior Lecturer in Biblical Studies at Trinity College at the University of Divinity, and a member of the Centre for Research on Religion put it, “Christians in Australia are not persecuted, and it is insulting to argue they are.”

Why now?

Amongst political operatives and observers, a key question about emerging political activism is not just “why?” but “why now?” Religious conservatives in Australia are suddenly much more politically active than before. There have been multiple attempts to stack Coalition party branches, and tenacious wandering of the corridors of power in search of “religious discrimination” protections. Why now?

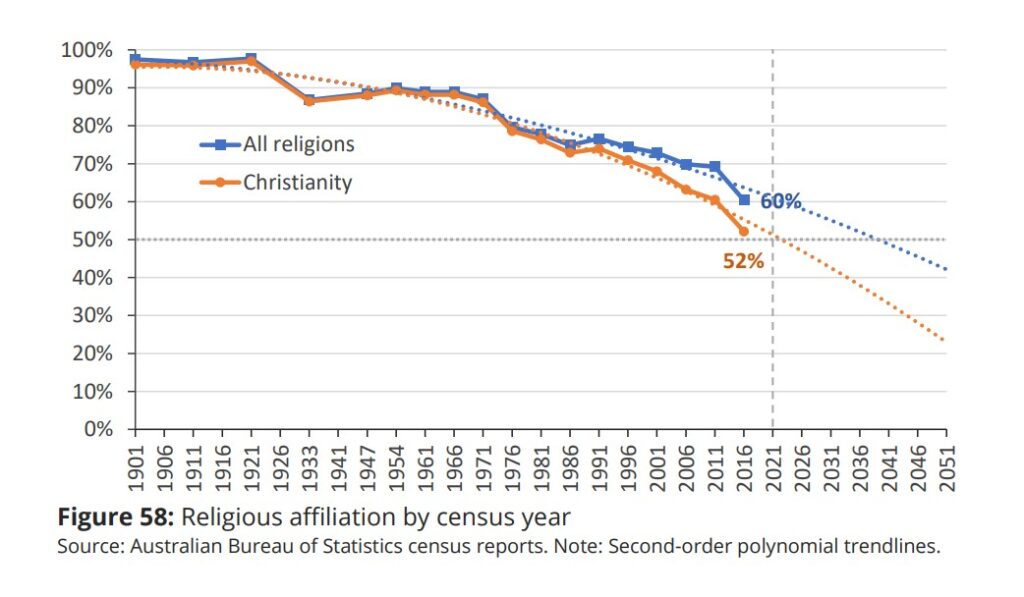

Obviously, one answer is the recent legalisation of marriage equality, which was vigorously opposed by religious conservatives. This is far from the whole answer, however. Another is the ongoing abandonment of Christian denominations by the laity, especially Notionals and Occasionals. Indeed, the 2016 census results will have come as a serious shock to religious conservatives, with its major drop in religious affiliation from even the long-term downward trend (see figure 58).

If the deconversion trend is repeated in this year’s census, which seems likely, Christianity would for the first time since Federation become a minority religion. Even religion in total might drop below 50%, though that is far less likely. And the Nones could come within 10% of total Christianity. No longer would Christian conservatives be able to refer to a presumed Christian “moral majority”: not that it has existed in reality for some time given the numbers of religious who never attend religious services and say they don’t belong to their religious organisation.

Therefore, it’s important to religious conservatives to achieve greater religious “protections” now, in case the Coalition government loses office at the next federal election — due by May 2022 — since Labor has shown less enthusiasm. And to get the job done before the ABS has a chance to announce Christianity to be a minority, around the middle of next year.

A range of tactics

Conservative religious coalitions have been employing a range of tactics. For example, they’ve adopted the tricky tactics of the USA’s religious right, claiming to be the victim while acting as the aggressor. As Whitaker argues, Christians in Australia are not persecuted, and it is insulting to argue that they are.

They’ve indulged in historical revisionism to claim that Australia is founded on Judeo-Christian tradition or values and would fall apart without them. However, in Australia, the expression “Judeo-Christian values” only makes its first appearance in 1974, and appears mostly in post-9/11 conservative rhetoric. It too was imported from the US, where it only appeared after the second world war.

They’ve attempted to paint Australia’s religiously affiliated as all spiritual believers, even though only a small minority are (as will be outlined in Part 2 of Religiosity in Australia). And they’ve attempted to appropriate non-religious Australians, SBNRs (spiritual but not religious), as really their people just missing in action. But SBNRs are in fact quite anti-establishmentarian, most don’t believe in God, and most oppose church doctrine on social matters.

This is not to argue that religion should be banned from the public square; that the religious should not be able to voice their views or seek representation. It is to argue that numerous sources of robust evidence establish that most Australians disagree with conservative religious views and believe they shouldn’t be privileged, or condition the rights and respect of fellow citizens.

Photo by Holli/Shutterstock.com