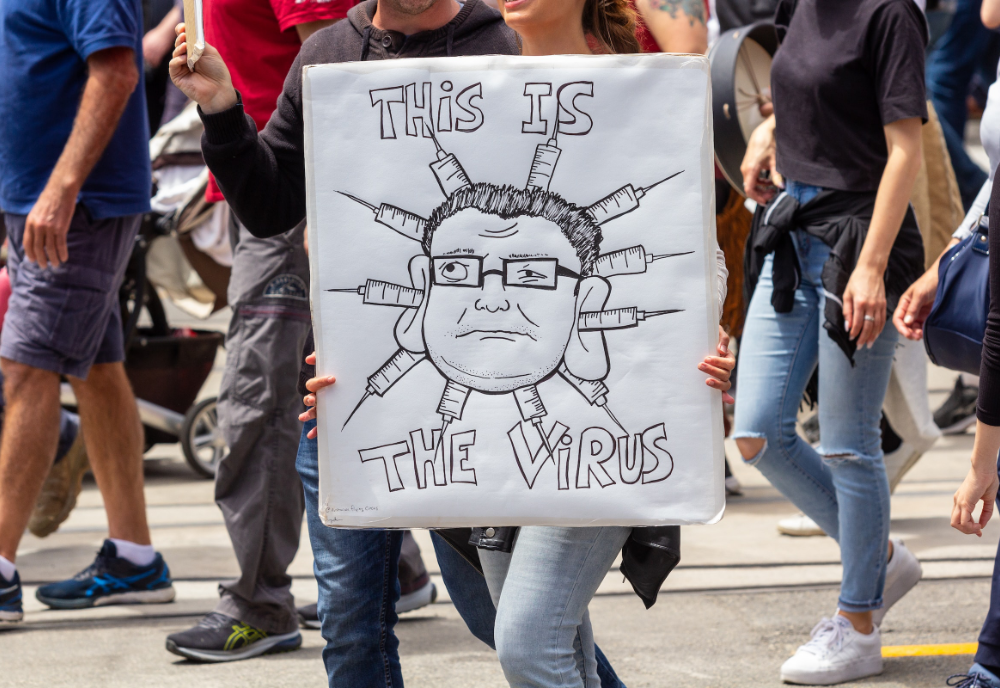

Conspiracy theories and medical misinformation about the coronavirus started to spread through social media sites almost immediately after the outbreak was first reported. The reasons for this are complex and talk to the way our brains have evolved over the last two million years.

Australians are being urged to refuse vital testing and self-isolation despite threats of a second wave of COVID-19 cases in Australia and elsewhere around the world. These theories are by no means a recent phenomenon, but social media has allowed people all over the world to convene in causes wherein ideas of uncertain merit gain traction and spread through society like a microbe-borne disease spreading through a human body. Today, the Moon and conspiracy theories go together like Neil Armstrong and nifty one-liners. About one in 10 young adults in America think the Jewish people caused the Holocaust.

In less than 20 years, the Internet and social media have had a deeper impact on our behaviour than all other media, affecting the way we think and how we relate to one another. Imagined and invented stories, and even outright lies, have become so prominent that we have come to doubt not only expert testimony and authority, but even our own sensibilities.

The reasons for this are complex and talk to the way our brains have evolved over the last two million years. In order to protect us from that lion hiding in the shrubs, our brains adopted a filtering mechanism that can rapidly weed out information that is not immediately essential to our survival and reproduction. This function of the brain is no less important today in the era of the Internet.

The Internet has not lived up to the imagined ideals of the 1990s as a democratic space that would provide everyone with direct information about all human knowledge. Our brains are now having to decipher between what are purportedly expert opinions, factual testimony and what can only be described as agenda-led, ill-informed crusades. This is arising from a competition over information, whether provided by subject matter experts or social media sites.

Worse, when this information is coupled with online social settings that resemble or evoke real-world social structures, a new interplay between the Internet and our social lives is created. It is a creation, however, that lacks real-world truths, real-world restraints and promotes deleterious, networked individualism on a global scale. It is a place where the value of truth and facts has been diminished and online opinions are ranked according to engagement so that a much ‘liked’ Facebook post can be more prominent than an encyclopedia entry.

Yet, we can’t blame the Internet wholly. The other thing our brains do is lead us away from objective reality by allowing a number of shortcuts, or deviations from rationality, that serve as entry points to so called cognitive biases. Our natural inclination is to believe or act in a particular way, because the people around us believe or do it. We favour ideas that confirm our existing beliefs and what we think we know. These biases might make us more efficient in everyday life, but they not only lead to errors of perception, they ‘explode’ online where our natural weaknesses are exploited.

Doubt is one of the most important of the myriad of cognitive biases that influence our judgment on the Internet. We all have a tendency to doubt, not just ourselves, but even in the things we actually witness. This isn’t necessarily new – Descartes’ 1644 dictum: Cogito, ergo sum is an example of arriving at a conclusion of certainty in the face of radical doubt.

We doubt things ranging from scientific discoveries, to promises made by politicians, to even recorded histories. But on the Internet, doubt is amplified by countless untrustworthy sources. We might assess digital content as far-fetched, photo-shopped, or special effects. Sure, author and philosopher Edward de Bono famously said: “Everyone has the right to doubt everything as often as he pleases and the duty to do it at least once,” but this right must come with equal due diligence in the people, platforms, and information in which we are to believe.

For example, we don’t a priori believe that man never walked on the Moon. We have all seen the grainy black and white images of Neil Armstrong taking his first step on the surface of the Moon. Yet, as many as one in 10 Americans do not believe the Moon landing really happened. Adherents of the 9/11 Truth movement dispute the mainstream account of the September 11 attacks of 2001. The Australian Department of Health has been forced to take steps to show that there isn’t a link between 5G and COVID-19 as some protestors seem to believe. But by utilising doubt a story can be told that will lead us, step by step, to a conclusion that seems completely unlikely at first glance.

Opinions on the Internet are often polarised into opposing camps, such that diversity of viewpoints and nuances ebb away leaving small highly motivated groups to attract so many clicks that their positions begin to appear much more representative than they really are.

This article was originally published in the December 2020 edition (vol. 119) of Australian Rationalist.

Photo by NASA on Unsplash