Democracy is difficult. Democracy is fragile. Democracy, in its most inclusive modus operandi, pushes the boundaries too far for many people.

As Winston Churchill said, no-one pretends democracy is perfect or all-wise.

“Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time…”

But democracy is also liberating. Full democracy liberates us not just from tyranny. It has given a voice to those who weren’t heard: men without property and status; women, considered inferior to men throughout history; Indigenous peoples, survivors of dispossession; people different to the dominant group due to their perceived colour, culture, politics and religion, gender and sexual preferences, disabilities, caste, status and wealth; and migrants and refugees seeking a safe haven or new opportunities.

Democracy allows such people to flourish and contribute fully to society, and this is of benefit to all of us.

In return, democracy requires only that: we tolerate differences; we don’t force others to believe the same things as us; and we recognise that thriving communities or societies are central to the wellbeing of humans. We are social creatures. Our communities must be greater than the sum of individual members doing their own thing and looking after themselves.

Most of all, democracy involves sharing. This is what has made it so hard to establish over the millennia. If we are to have an equal voice, we need to have equal opportunities. If all people are to contribute to our way of life to their fullest extent, we need to help them; we need to look after everyone in our society.

This requires a shift of wealth. We have to pay taxes and give up some of our privileges. We have to be open-hearted, accepting and empathetic. We need to have the ability to say “there but for the vagaries of fate I go, too”, and so believe in justice for all. We have to give up wealth, power and the conviction that we are always superior, or that our will must prevail.

We also have to tolerate the uncertainty that comes with not being in control. Uncertainty spawns fear – fear of losing what makes us who we are and what makes us feel safe and comfortable. Fear leads to prejudice, discrimination, hatred, violence and oppression.

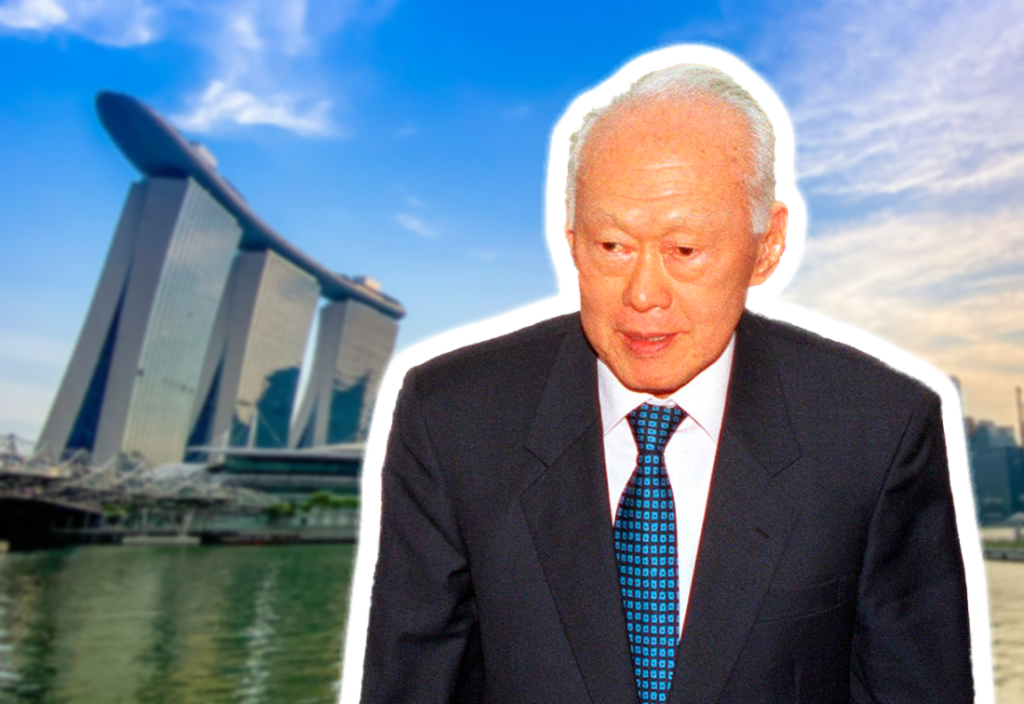

On the other hand, authoritarian regimes with strong leaders offer us the prospect of certainty, control, and victory over others – the ability to repress or get rid of those who may take our wealth from us or challenge our views, even if they are our fellow citizens.

Being part of an elite group and having power helps maintain the illusion that we are in control, that we are significant and entitled to do as we wish, or even invincible. And when things are not going as we like, we can blame non-elite groups.

It is not surprising that psychopaths and narcissists are found at the head of many organisations. What is strange is how easily we are duped or cowed by them.

Nonetheless, many people have genuine concerns about the pace of change in our society.

History is replete with autocratic leaders who were cruel, vindictive, entitled, incompetent, erratic, greedy, oblivious to the needs of the populace and even mad. As a result, most people who have lived on Earth have lived in miserable conditions and had little say in how they lived their lives. Slavery, indentured labour and serfdom were common.

Most of all, democracy involves sharing. This is what has made it so hard to establish over the millennia. If we are to have an equal voice, we need to have equal opportunities.

Authoritarian rule was the norm; liberty, equality and freedom were extremely rare. Even two hundred years ago, hardly any country in the world was a democracy. Furthermore, almost 80 per cent of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty, and only small elite groups enjoyed a high standard of living.

Although ancient Greek city states experimented with restricted forms of democracy thousands of years ago, it really wasn’t until the early 20th century that more inclusive democracies developed. The self-sacrifices made by people in the 19th and 20th centuries to improve social justice and extend democratic processes made a major impact on the quality of the lives of ordinary people.

After the end of World War II, and ending of colonialism in many places, the percentage of countries that were liberal democracies tripled to almost 10 per cent by 1950. During the 1980s, and after the end of the Cold War, there was an even greater expansion of democracies. By 2000, more than one-fifth of countries (22 per cent) were liberal democracies.

People who live in these countries are lucky – they are a small and privileged minority of the world’s population. Most people live in authoritarian countries, or limited or flawed democracies. Over 1.4 billion of these people live in China, which scored incredibly low on the Electoral Democracy Index.

The world is becoming more authoritarian. In 2023, 42 countries became more autocratic. There has been a significant reduction in the freedom and power of ordinary people to determine how they are governed. The most populous country in the world, India, has become less democratic to the point that it could be classified as an electoral autocracy. In 2023, it scored only 0.38 (out of 1) on the Electoral Democracy Index.

Democracy is declining in the so-called ‘land of the free’ so much so that analysts no longer consider the United States a full democracy but a failed democracy. If the first month of Donald Trump’s second presidential term is any indication, liberal democracy, freedom of choice, justice, the rule of constitutional law and respect for human rights are vanishing at an astonishing rate.

Australia has just displaced New Zealand as the tenth happiest country in the world. We join a fairly consistent top ten of happy countries. Countries with social democratic government have tended to lead the list, although some have recently become more conservative. One of the reasons, it seems, has been the influx of refugees into these countries. We tend to become more conservative when we feel under threat.

Truly inclusive democracies are very rare and precious. The question is: how much are we prepared to sacrifice to prevent a Trumpian vision from turning Australia into a failed democracy with a dystopian future?

Published on 19 February 2025.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Element5 Digital on Unsplash.