The virtue of intellectual humility is getting a lot of attention. It’s heralded as a part of wisdom, an aid to self-improvement and a catalyst for more productive political dialogue. While researchers define intellectual humility in various ways, the core of the idea is “recognising that one’s beliefs and opinions might be incorrect.”

But achieving intellectual humility is hard. Overconfidence is a persistent problem, faced by many, and does not appear to be improved by education or expertise. Even scientific pioneers can sometimes lack this valuable trait.

Take the example of one of the greatest scientists of the 19th century, Lord Kelvin, who was not immune to overconfidence. In a 1902 interview “on scientific matters now prominently before the public mind,” he was asked about the future of air travel: “(W)e have no hope of solving the problem of aerial navigation in any way?”

Lord Kelvin replied firmly: “No; I do not think there is any hope. Neither the balloon, nor the aeroplane, nor the gliding machine will be a practical success.” The Wright brothers’ first successful flight was a little over a year later.

Scientific overconfidence is not confined to matters of technology. A few years earlier, Kelvin’s eminent colleague, A. A. Michelson, the first American to win a Nobel Prize in science, expressed a similarly striking view about the fundamental laws of physics: “It seems probable that most of the grand underlying principles have now been firmly established.”

Over the next few decades – in no small part due to Michelson’s own work – fundamental physical theory underwent its most dramatic changes since the times of Newton, with the development of the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics “radically and irreversibly” altering our view of the physical universe.

But is this sort of overconfidence a problem? Maybe it actually helps the progress of science? I suggest that intellectual humility is a better, more progressive stance for science.

As a researcher in philosophy of science for over 25 years and one-time editor of the main journal in the field, Philosophy of Science, I’ve had numerous studies and reflections on the nature of scientific knowledge cross my desk. The biggest questions are not settled.

How confident ought people be about the conclusions reached by science? How confident ought scientists be in their own theories?

One ever-present consideration goes by the name “the pessimistic induction“, advanced most prominently in modern times by the philosopher Larry Laudan. Laudan pointed out that the history of science is littered with discarded theories and ideas.

It would be near-delusional to think that now, finally, we have found the science that will not be discarded. It is far more reasonable to conclude that today’s science will also, in large part, be rejected, or significantly modified, by future scientists.

But the pessimistic induction is not the end of the story. An equally powerful consideration, advanced prominently in modern times by the philosopher Hilary Putnam, goes by the name “the no-miracles argument”. It would be a miracle, so the argument goes, if successful scientific predictions and explanations were just accidental, or lucky – that is, if the success of science did not arise from its getting something right about the nature of reality.

There must be something right about the theories that have, after all, made air travel – not to mention space travel, genetic engineering and so on – a reality. It would be near-delusional to conclude that present-day theories are just wrong. It is far more reasonable to conclude that there is something right about them.

Setting aside the philosophical theorising, what is best for scientific progress?

Of course, scientists can be mistaken about the accuracy of their own positions. Even so, there is reason to believe that over the long arc of history – or, in the cases of Kelvin and Michelson, in relatively short order – such mistakes will be unveiled.

It would be near-delusional to think that now, finally, we have found the science that will not be discarded. It is far more reasonable to conclude that today’s science will also, in large part, be rejected, or significantly modified, by future scientists.

In the meantime, perhaps extreme confidence is important for doing good science. Maybe science needs people who tenaciously pursue new ideas with the kind of (over)confidence that can also lead to quaint declarations of the impossibility of air travel or the finality of physics. Yes, it can lead to dead ends, retractions and the like, but maybe that’s just the price of scientific progress.

In the 19th century, in the face of continued and strong opposition, the Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis consistently and repeatedly advocated for the importance of sanitation in hospitals. The medical community rejected his idea so severely that he wound up forgotten in a mental asylum. But he was, it seems, right, and eventually the medical community came around to his view.

Maybe we need people who can be committed so fully to the truth of their ideas in order for advances to be made. Maybe scientists should be overconfident. Maybe they should shun intellectual humility.

One might hope, as some have argued, that the scientific process – the review and testing of theories and ideas – will eventually weed out the crackpot ideas and false theories. The cream will rise.

But sometimes it takes a long time, and it isn’t clear that scientific examinations, as opposed to social forces, are always the cause of the downfall of bad ideas. The 19th century (pseudo)science of phrenology was overturned “as much for its fixation on social categories as for an inability within the scientific community to replicate its findings,” as noted by a group of scientists who put a kind of final nail in the coffin of phrenology in 2018, nearly 200 years after its heyday of correlating skull features with mental ability and character.

The marketplace of ideas did produce the right results in the cases mentioned. Kelvin and Michelson were corrected fairly quickly. It took much longer for phrenology and hospital sanitation – and the consequences of this delay were undeniably disastrous in both cases.

Is there a way to encourage vigorous, committed and stubborn pursuit of new, possibly unpopular scientific ideas, while acknowledging the great value and power of the scientific enterprise as it now stands?

Here is where intellectual humility can play a positive role in science. Intellectual humility is not skepticism. It does not imply doubt. An intellectually humble person may have strong commitments to various beliefs – scientific, moral, religious, political or other – and may pursue those commitments with vigor. Their intellectual humility lies in their openness to the possibility, indeed strong likelihood, that nobody is in possession of the full truth, and that others, too, may have insights, ideas and evidence that should be taken into account when forming their own best judgments.

Intellectually humble people will therefore welcome challenges to their ideas, research programs that run contrary to current orthodoxy, and even the pursuit of what might seem to be crackpot theories. Remember, doctors in his time were convinced that Semmelweis was a crackpot.

This openness to inquiry does not, of course, imply that scientists are obligated to accept theories they take to be wrong. What we ought to accept is that we too might be wrong, that something good might come of the pursuit of those other ideas and theories, and that tolerating rather than persecuting those who pursue such things just might be the best way forward for science and for society.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

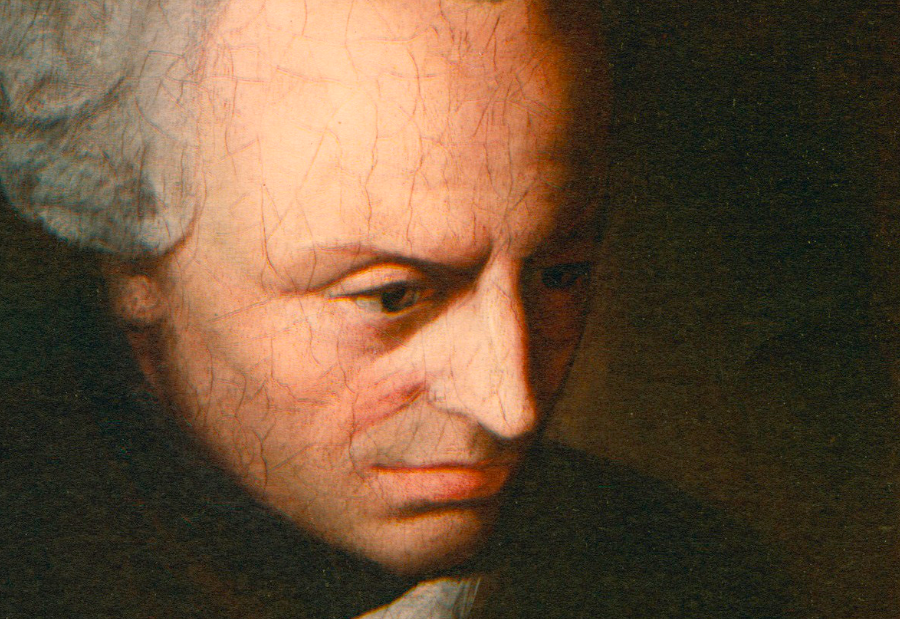

Image: History in HD (Unsplash).