There is a wonderful film called the The Book Thief, which is based on a novel by Markus Zusak, an Australian-German writer. It is about silent courage in times of great danger.

Set in a town in Germany during the Second World War, it is about death, but also about the choices faced by an ordinary German couple who adopt a young girl and then teach her to read and love books – books she later sees burnt by the Nazis.

The father intervenes in the ill-treatment of a Jewish shopkeeper he knows and pays a terrible price. Later, they harbour a young Jewish man in their house, taking incredible risks.

On the one hand, the father realises that his actions threaten not only his own life but the lives of his family members. On the other hand, are his principles and promises.

I have often pondered what I would have done if I had lived in Germany in the late 1930s and during the war. No easy answers come to mind.

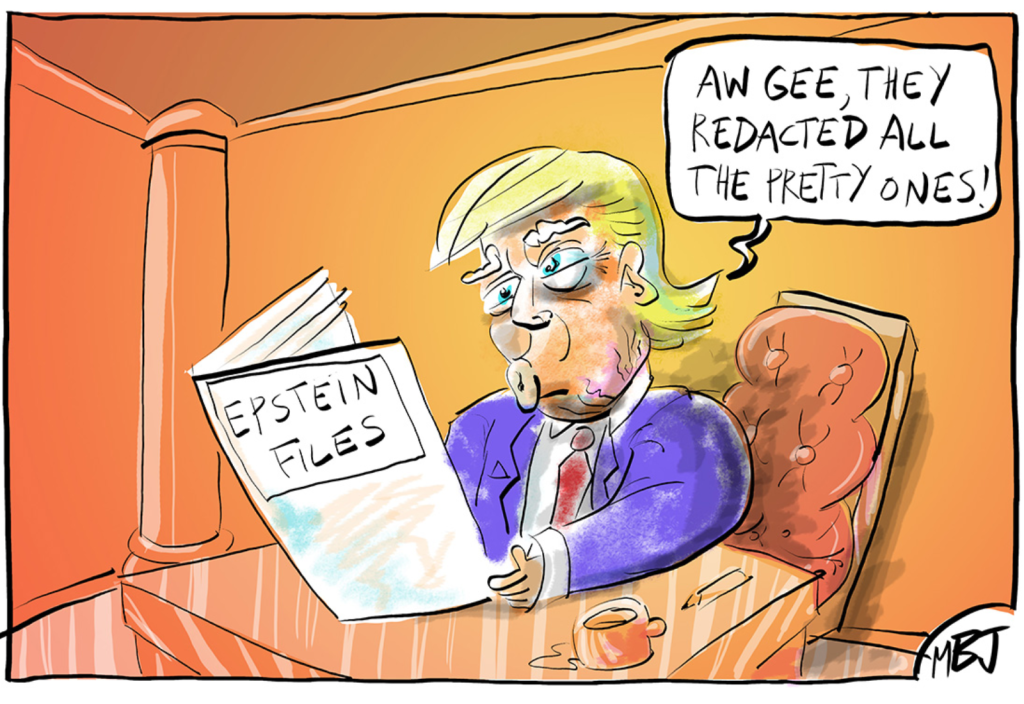

Likewise, I wonder what I would do if I lived-in present-day America where the regime of Donald Trump has Nazi overtones. It seems as if many Americans have watched passively as their democracy and freedoms have been eroded away.

In reality, the window to stop that happening was very short. It needed to have occurred immediately after Donald Trump was elected President and had not quite organised his systematic assault on human rights in America and his campaign against the rest of the world.

I guess his opponents were still dazed that things had gone so awry that he was elected in the first place. Maybe they thought things couldn’t get too bad in a democracy, although the writing was on the wall for everyone to see.

Being older now, without a family to depend on me, and with nothing much to lose, I think I might have joined the resistance, or a Kamikaze assassination squad, or at least faced off against the National Guard.

The problem is whether such actions, with the terrible sacrifice they require, achieve anything. It is a horrible thing to realise that you are powerless no matter what you do.

When I sit down to contemplate the existential threats we face – global warming, overwhelming and long-lasting pollution, over-population, over-consumption, poverty and inequality, depletion of resources, pandemics, destruction of natural habitats and extinction of unique animals and plants, wars waged on free states, the possibility of nuclear war, the displacement of people from their homes, lack of water and food, and the violence that causes – I am overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the tragedy our actions are going to cause.

So many things, including a better future for our children, will perish in a terrible and wholly preventable way. I feel unhinged by the enormity and relentlessness of it all. But life goes on.

How do we deal with the disparity between everyday life and the cruelty, ignorance and greed that will destroy it?

Many people in the past have faced situations of living in a nightmare where they still need to keep going, hoping for the best but enduring the worst. In such circumstances, how do people retain their decency and self-respect?

The first step is, of course, to realise that the only thing you really control is yourself. Even when you are unable to behave as you would like, you can, with great effort, still control your feelings and thinking.

Buddhism offers a way. It recognises that all life is suffering in the sense that there will inevitably be pain, grief, dissatisfaction, frustration, unfilled desires, and we may not be the person we want to be. It is how we deal with this fact that is important.

Buddhism offers ways to deal with difficult times through acceptance of reality, reducing attachment to things and people, and living in the present moment. It recognises that all things are impermanent. So Buddhist philosophy sees difficulties as opportunities for growth and developing wisdom.

Turning inward, it is possible to observe how we react and behave more clearly without judgment, and to practice compassion for ourselves and other living things. Many people use mindfulness and meditation techniques used by Buddhists to shift their perspective and to calm the mind.

The two-arrow analogy helps us realise that it is better to only suffer once. The ‘first arrow’ of suffering is the unavoidable suffering involved in life, whether it be physical pain, difficult circumstances, or loss. The ‘second arrow’ is avoidable – it is how we do ourselves harm by railing against the suffering we experience through anger, blaming, fear, regret, anxiety, and worrying. None of these things alter the outcome of the suffering; they just make us miserable and unable to cope or adapt to the situation. In doing so we squander opportunities for satisfaction in our lives.

We can also become Stoical. My favourite Stoic is Marcus Aurelius, who only left fragments of his philosophy set out in his books Meditations, but they seem relevant even now. He lived between 121CE and 180CE and ruled the Roman Emperor from 161CE to 180. He was the last of the Five Good Emperors and the last emperor of the Pax Romana, an age of relative peace, calm, and stability for the Roman Empire lasting from 27BC to 180CE. Nonetheless his life had many challenges. For example, the Antonine Plague broke out around 165 and devastated the Roman Empire, killing between five to ten million people.

Many of Marcus Aurelius’s children died young. It is reported that he said

One man prays: ‘How I may not lose my little child’, but you must pray: ‘How I may not be afraid to lose him’.

He quoted from the Iliad what he called the “briefest and most familiar saying […] enough to dispel sorrow and fear”:

leaves,

the wind scatters some on the face of the ground;

like unto them are the children of men.

The Stoic approach has much in common with Buddhism. It recommends focusing on the things in life that you can control, such as your thoughts, judgments, actions and character. It recognises that other things that you think you can control, such as your health, wealth, reputation and the opinions of others, can be lost very easily. So spend your time on what is really important.

Stoicism also believes it is important to embrace hardship as a natural part of life and an opportunity to grow. Marcus Aurelius said: “What stands in the way becomes the way.”

The Stoics also recommended the cultivation of virtue, wisdom, courage and self-control – which anyone could achieve and which provide a strong foundation for withstanding difficult times.

They believed that meditation helps, particularly premeditatio malorum, used in periods of calm to rehearse in your mind adverse situations you might experience in the future and how you might handle them. When misfortune arises, instead of being overwhelmed with fear or anger you are able to react in a more constructive way.

Like the Buddhists, Stoics also believe in focusing on the present, finding the good in different situations or lessons that can be learnt, and seeking help and inspiration from those who have overcome challenges in life.

Stoicism can be a bit grim, and I think dealing with difficult times and the constant threat of impending doom requires some of the pleasure strategies of Epicurus.

The philosophy of Epicurus is often labelled as hedonism. Epicurus may have advocated for hedonism – making pleasure the most important pursuit for humans – but his ideas were far more measured than the wanton, expensive and unbridled overindulgence in pleasure we think of hedonism today.

For Epicurus, hedonism meant giving up unnecessary desire and achieving peace and tranquility by taking pleasure in the simple things of life, such as conversations with friends or philosophical discussion in a garden setting with simple food and drink.

When we say, then, that pleasure is the end and the aim, we do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or the pleasures of sensuality, as we are understood to do through ignorance, prejudice, or wilful misrepresentation. By pleasure we mean the absence of pain in the body and trouble in the soul. It is not an unbroken succession of drinking bouts and of revelry, not sexual lust, not the enjoyment of fish and other delicacies of a luxurious table, that produces a pleasant life. It is rather sober reasoning, searching out the grounds of choice and avoidance, and banishing those beliefs that lead to the tumult of the soul.

In a letter, written to a friend when he was dying, he said:

I have written this letter to you on a happy day to me, which is also the last day of my life. For I have been attacked by a painful inability to urinate, and also dysentery, so violent that nothing can be added to the violence of my sufferings. But the cheerfulness of my mind, which comes from the recollection of all my philosophical contemplation, counterbalances all these afflictions.

So turn off the news, seek for a little pleasure amongst the darkness, whether in a secluded garden or by watching a fantasy movie or a documentary of the wonderful things people do. Dream of becoming a Jedi knight or joining Starfleet!

Clarify what is really important to you at the most basic level and what your core values are. Practice gratitude, especially for the good people in the world. Practice gratitude for yourself in all your manifestations. Enjoy the company of family, friends and like-minded people. Take time out to do something that takes up all your attention so time passes without your awareness. And, when you have the opportunity, act on what you believe in.

Enjoy what you have while you have it as nothing is permanent.

Published on 18 October 2025.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Alexandra Smielova on Unsplash.