This article is the second part in a two-part series. Read the first part here.

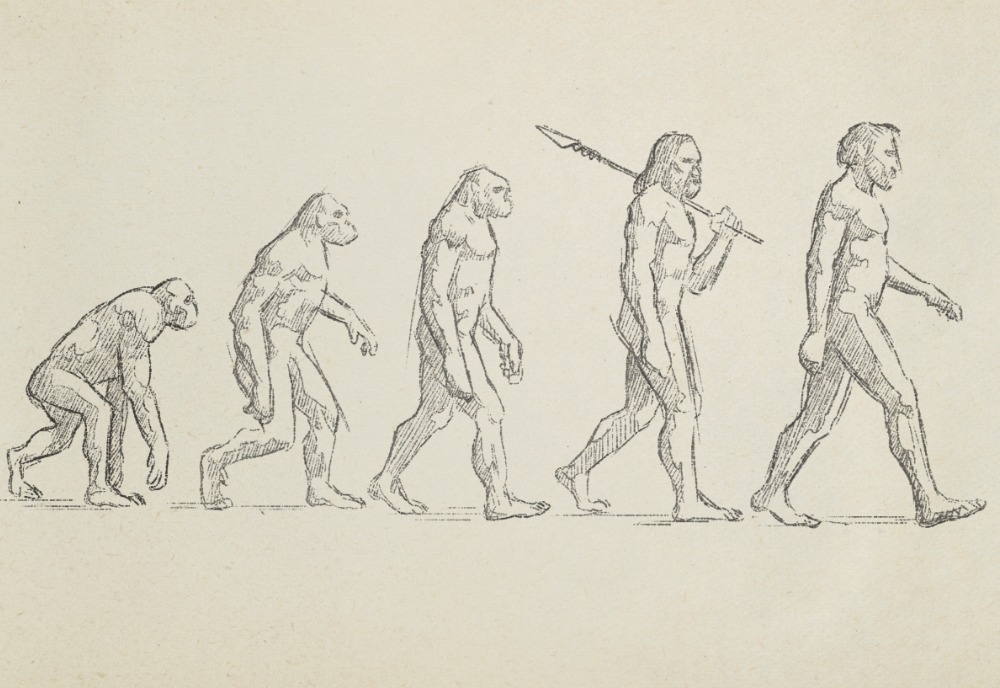

Homo erectus (about 1.8m up to 0.5m years ago)

After the rapidly expanding australopithecines, it is a relief to find the next 1.5 million years of human evolution looking rather simpler. One hominin – Homo erectus – becomes supreme, and the archaeology is dominated by one great theme: the handaxe or Acheulean tradition.

Homo erectus first appeared as long as 2 million years ago, and was living in southern, eastern and northern Africa as well as the Middle and Far East, according to its fossil remains. It was far more human than earlier hominins, with brain size ranging from about 500cc in early examples to more than 1,000cc in later times – around 70 per cent of our modern cranial capacity. Its limb proportions were fairly modern too, showing a striding form of bipedalism, evident both at Dmanisi in Georgia, and in the near-complete skeleton of “Turkana Boy” in Kenya.

Homo erectus was wide-ranging and capable, as its tools confirm, having been found all over Africa and most of Asia. The handaxe form emerged around 1.75 million years ago in eastern Africa, probably as a good multi-purpose solution to everyday needs, and again made from lava or quartzite. The handaxe concept spread very widely; indeed, this may have been the first great diffusion of a “package of ideas”. Some were so finely worked that they have been deemed the first art – or at least a sign of aesthetic feeling.

In fact, Homo erectus may represent a group of similar species that existed in parallel – and that in some locations, could be quite varied. The single site of Dmanisi has offered up as much variety in five skulls as has been found across Africa. Existing finds make a giant “geographical donut”, with nothing in the middle across the whole of southern Asia from Georgia to China.

While Far Eastern Homo erectus was very similar to the African species, there are anomalies in this part of the story. For example, a remarkable and diminutive hominin species, Homo floresiensis – discovered in 2003 on the remote island of Flores in Indonesia, and often known as “the Hobbit”– had anatomical details, especially of its wrists, to suggest it could have been descended from an earlier Homo than Homo erectus.

In southern Africa, meanwhile, Homo naledi was a primitive-seeming species that dates back just 300,000 years, and seems likely to have been a small-brained descendant of an early Homo erectus. It may have lived in gallery forest alongside streams, and survived in splendid isolation.

The handaxes, too, were not all the same. The idea of making them seems to have spread far and wide, but not everywhere – they are absent in much of the Far East, for example. While some are now known from China, the famous fossil site of Zhoukoudian near Beijing – where remains of more than 40 Homo erectus individuals have been found – lacks them entirely.

In Europe, ice ages and temperate periods alternated many times, so across the last 1 million years much of the early record has been erased by ice sheets. There is no definite evidence of Homo erectus but a probable sister species, Homo antecessor, lived in Atapuerca, northern Spain, perhaps as long ago as 1.4 million years. In this climatically challenging environment, we could wonder how “primitive” humans survived – but at the Arago cave in the Pyrenees, near France’s Mediterranean coast, we know they were butchering reindeer 600,000 years ago and so able to endure the most severe cold.

There are three main things we can say about the hominins of this long period up to half a million years ago: they were widely dispersed (hence highly adaptable and resilient); technically capable to the point that at least some of them used fire; and were evolving large brains that reflected their highly social nature.

Fire seems to have been very important in human adaptation. It fits with ideas about cooking – the need for high-quality food to fuel the brain – and a reordering of the day to provide more social time, especially in the evening. Fire was also a key enabler of other technologies, in time allowing these early humans to begin pottery and metalworking.

The origins of fire’s “domestication” are far from certain, but are likely to date back at least 1 million years. Opportunistic use probably came before full control, with the ability to kindle fire eventually releasing humans from the need to keep it alight for long periods.

In brain size, Homo erectus was certainly not static. Contrary to a general impression that most of the great brain enlargement in Homo is relatively recent, there was already some overlap with modern humans half a million years ago.

Although it is natural to think that to be clever is an end in itself, large brains like ours are costly enough to take 20-30 per cent of our energy, and they have to pay their way. Most species succeed with far less than hominins, and to treble brain size in 2 million years is a remarkable phenomenon. Such an expansion was only possible through a high-quality diet and reduction in the size of other major organs.

As the large brain is energetically expensive, it must have had evolutionary drivers. One of the most appealing is the “social brain hypothesis”, whose core idea is that in some environments, ecological survival favoured larger groups. We know from regular stone tool transport distances of 5-10 km, and occasional ones of 20-30km, that hominins were ranging much further than apes even 2 million years ago. The social management of such groups is very demanding, and may have been a spur towards developing larger brains.

The acceleration in change that is such a feature of modern life seems to have started around half a million years ago. In Africa, Homo erectus gave way to larger-brained descendants such as Homo heidelbergensis, which was also present in Europe.

But in archaeology, major developments were seen even before the first early modern human fossils emerged. Two key developments were the appearance of projectile (spear) points and the long-distance transport of materials. The stone spear points indicated that their makers had mastered hafting, and hence had knowledge of fixatives such as glue or twine. In southern Africa, we see the beginnings of these developments as long as 400,000 years ago.

With their bigger brains, larger social groups and better weapons, hominins developed and honed their unique hunting techniques, often working by ambush and taking prime animals rather than the old and young. While that pattern may date back more than a million years, in the last 50,000 years this practice may have been so intense that it contributed to the demise of many large animals, including the mammoth, mastodons, and giant marsupials.

In all this, there is plentiful evidence of high skill. In the Levallois technique, which few can reproduce today, the maker prepared a stone core by careful flaking, and had to “see” the artefact before releasing in one blow.

Such skills could approach art. Numbers of ancient pieces including some of the handaxes would qualify as art by modern definitions, although we know little about the past intent. Such finds suggest the basic abilities for art were in place as much as a million years ago, but its projection into non-utilitarian forms gives another level to the evidence of human intellect.

Modern humans (from around 300,000 years ago)

Many people look at human evolution chiefly to explain us, Homo sapiens. But we are the culmination of a long process of evolution – no more than 5 per cent of the whole hominin story by time spent on this planet.

Until the 1980s, our species was thought to have first appeared around 40,000 years ago in a “human revolution” – an explosion of creativity marked by the flowering of cave art and sophisticated tools. However, many events in this analysis were incorrectly concertinaed together by a ceiling in radiocarbon dates, which the rapid decay rate of carbon-14 limited to a maximum age of about 40,000 years.

Since then, new dating techniques based on other radioisotopes and new finds have expanded the timescale for the existence of Homo sapiens by almost a factor of ten. In fact, the first early modern humans, closely resembling us, appeared about 300,000 years ago in northern and eastern Africa. This drastic change of timescale alters our perspective in ways that are still being explored.

For a start, we now know that for a long period, the earliest modern humans were not alone. They existed alongside Homo neanderthalensis, the Neanderthals – the people of the north, ranging from western Europe to Siberia – for hundreds of thousands of years.

To the east, DNA studies have recognised a probable sister group of the Neanderthals, the Denisovans – best known from Denisova cave in the Altai mountains of Siberia – while to the south, Homo naledi was still there, and the Kabwe skull from Zambia is evidence for at least one other species.

Astonishing progress in genomic research has shown that the Neanderthals and Denisovans were separate species, but so closely related to our H. sapiens ancestors that interbreeding was possible. Does the ability of these species to interact imply the existence of language? As with fire, language origins have been one of the major debating points within palaeoanthropology. Small clues are enigmatic.

More than 2 million years ago, a mutation reduced the power of the chewing muscles in human ancestors. That may indicate they were doing more food preparation, but also possibly making more controlled use of their mouths. Expanded nerve outlets in the thoracic vertebrae appeared in Homo erectus, indicating the millisecond control of breathing that is necessary for language.

And later, 400,000-year-old Homo heidelbergensis remains from Atapuerca in northern Spain had perfectly preserved ear canals which were tuned to the frequencies used in human language. As these Atapuerca hominins were probable Neanderthal ancestors, there is a good chance that at least a simple form of language was very widespread at this point, if not earlier.

Paintings first appeared – or were preserved – around 50,000 years ago, but beads and ornaments can be traced back much earlier. The oldest so far are shell beads from Es-Skhul cave on Mount Carmel in Israel, dating back about 130,000 years. They mark out personal identity, and hence the idea that one person can appreciate these signals in another. Shell beads occurred again at Blombos in South Africa about 70,000 years ago, along with a piece of engraved ochre.

Burials have a similar antiquity: both Neanderthal and early modern burials occurred from about 130,000 years ago – although older finds such as the numerous human remains in one cave at Atapuerca, or cutmarks on a skull at Bodo in Ethiopia, may indicate there was already a special interest in human bodies. The burials suggest that early humans had a strong idea of the needs of others.

Homo erectus at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum (Ryan Somma, Flickr CC).

Some burials – both of early moderns and Neanderthals – had red ochre smeared on the bodies. This is likely to have carried symbolic significance. “Symbolism” has played a crucial part in all modern human behaviour, underpinning language, religion, and art. However, studying its origins presents pitfalls, because other animals seem capable of using symbols, as when a chimpanzee offers a clipped leaf to another.

The line between such “signs” and symbols is easily blurred. But the projection of symbols into the outside world in the form of material objects is a measurable step, so long as they survive. The beads and burials are among the earliest evidence of behaviour which may, in fact, have had much deeper origins.

The great breakout (about 100,000 years ago)

More than 100,000 years ago, the early modern humans began to expand outside Africa, leading to the greatest diaspora in human history. Variation in modern human DNA preserves geographic signals that tell us something about past population movements. Even better, fossil DNA can be isolated from bone specimens up to about 50,000 years old in cool climates, and sometimes even older.

The results confirm that the Neanderthals were a truly separate species, with their ancestors separating from ours between 500,000 and 700,000 years ago, and living on until about 40,000 years ago.

Some of the clearest genetic signals come from parts of the genome that do not recombine each generation – that is, the Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA. These have allowed scientists to assemble “family trees” which show that all modern humans (Homo sapiens) are related within about 150,000 years. They also indicate, along with the archaeological evidence, that modern humans surged out of Africa after that date, sweeping around the world and eventually completely replacing other hominins such as the Neanderthals and Denisovans – although some of their genes survived in us, thanks to rare past matings between species.

In essence, this was a great population expansion rather than a migration. Populations remained in Africa and along the way, but this astonishing wave of advance headed east across Asia, then north into Europe, and ultimately to all parts of the world.

The start was necessarily from north-east Africa, offering a land route into the Middle East and, at times of low sea-level, a likely southern one to Arabia. Climate changes almost certainly played a major part: each time “green Sahara” became desert Sahara in the rhythmic changes of the ice ages, this would pulse people out into the Levant.

Modern humans are visible there around 130,000 years ago – but Neanderthals succeeded them around 80,000 years ago as conditions became colder again. Probably by then, the great move east had already happened: early modern humans had covered the 12,000 kilometres to Australia as long as 70,000 years ago.

At least 45,000 years ago, they were in north-east China, perhaps arriving by a route north of the Himalayas. From there, it was 6,000km to the Bering landbridge that would lead to Alaska. By 14,500 years ago, modern humans were in Monte Verde, Chile after an astonishing 15,000km journey down the Americas.

The severe cold of the last glacial maximum, 20,000 years ago, must have slowed down this progress. Sea levels dropped more than 100 metres, and northern populations were rolled back by the ice advances. Many American archaeologists still believe the first settlement in their continent began after this, but footprint trails in New Mexico dated to the 20,000s BCE are part of growing evidence for earlier dates.

Such debates do not alter the big picture: at times, our direct ancestors were progressing about a kilometre every five years; at others, they were shooting forward great distances. Some of them, at least, had become adventurers, with something like the wanderlust characteristic of modern explorers.

They travelled both inland and along the coasts, by foot and certainly by boat. They covered high and low terrain, in warm and cold, wet and dry – all the while, living by the ancient and enduring adaptation of hunting and gathering.

Last of the Neanderthals (about 40,000 years ago)

Historically, studies in human evolution greatly emphasised Europe. While the balance has rightly been redressed to a global perspective in the last 50 years, Europe remains important in our record – both because northern climates better preserve organic remains including DNA, and because this rich record has been studied intensively for more than 150 years.

Amid the great diaspora of early modern humans, a newer perspective is that, by the time the last Neanderthals were gone from Europe, fully modern humans had already dispersed through Australia and throughout the Far East. But these events remain puzzling because the Neanderthals had held their own with early modern humans for hundreds of thousands of years across a fluctuating frontier, and were dominant in the Middle East as late as 60,000 years ago.

The Neanderthals have an enduring fascination because they are so like us and yet so different. They were stocky and strong, and had a brain size as large as ours. Their abilities have been debated for more than a century, but there is strong evidence that they are an alternative humanity rather than an inferior humanity. They had full control of fire, made bone tools, and used pigments as well as burying their dead.

Their replacement by modern humans was completed between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago. What gave the moderns the edge? It could be that a known series of rapid climate fluctuations destabilised the Neanderthal populations. There is evidence that they were living in small groups, under stress and with significant inbreeding, and a consensus now is that demographic factors were a main cause of their disappearance.

In Europe, the traditional idea of a “creative revolution” was highlighted by the disappearance of the Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago, and the arrival of new populations with new toolkits – the Upper Palaeolithic with its blade tools, bone tools and artwork.

Elsewhere, such advanced traits often appeared earlier. At the moment, the earliest known cave art comes from Karampuang Hill on Sulawesi, Indonesia, where there are representations of humans and animals dated to 51,000 years ago.

European art is considerably later, except for some markings which could have been made by Neanderthals, who certainly used pigments. From around 40,000 years ago, there began to be other representations, including one of exceptional importance: a small statue of mammoth ivory found in a cave in what is now southern Germany. It combines the head of a lion with a human body, showing the artist’s ability to morph a 3D form which may have had religious significance.

By the time of the 20,000s BCE, we see many signs of new technologies and skills: basketry in the Gravettian phase of central Europe; the first pottery in China; polished axes in Australia and New Guinea; and specialised use of marine resources in South Africa, Indonesia and elsewhere. Probably, there were also the first domesticated dogs, who became well-documented in Europe about 15,000 years ago.

After the ice (about 20,000 years ago)

Following the glacial maximum, there came a steady return to warmer conditions, culminating in the period we call the Holocene. Ice sheets retreated to the north, temperate vegetation appeared and the sea came up, with profound effects on coastal settlement around the world.

Along with new environmental stresses, around 12,000 years ago came the next major shift in human adaptation: the agricultural revolution. The domestication of plants and animals soon led to vast increases in population numbers. Villages, towns and civilisations followed, ultimately made possible by the control of food supplies that hunters and gatherers could never have, but also dependent on technological advances and complex social behaviour.

It is easy to take for granted that we are human. But knowing the human evolutionary story, even if at times from only a few fossil fragments, shows it could easily have been otherwise. Had climate patterns been slightly different, Neanderthals might have survived. They or the Denisovans could be carrying the flag of progress, in a different way and at a different pace.

Today, we are still not on top of things. The greatest changes in the world are humanly created, and they stem above all from our vast numbers. For at least 99.5 per cent of the time of Homo, our ancestors lived as hunters and gatherers, with global numbers no more than a few million. Yet now, over a single human lifespan, the global population has grown fourfold, from 2 billion to 8 billion.

The story of human evolution is about more than bones and stones. It helps us to see our many strengths and limitations. The strengths include an ability to manage rapid cultural change, especially in technology – the key to our survival over a very long period, and vital for coping with environmental change. But this ability is also having many unforeseen consequences to our planet and its biodiversity, and to our own human societies.

It is a triumph that most of the 8 billion humans alive today are living relatively happily and, thanks to modern medicine, for longer than ever before. But it is all part of a high-risk species strategy that has characterised the story of human evolution from its earliest origins nearly 8 million years ago.

Throughout this story, success has regularly thrown up new sets of problems. Our ancient ancestors had no choice but to forge forwards into the unknown, adapting to survive. Many times over, they surmounted challenges at least as great as those we face today.

This article was originally published in The Conversation. It is republished here as a two-part series.

Main photo: Shutterstock