In late October 1914, following a long period of rising tensions between the two nations, the Ottoman navy conducted a number of raids against Russian shipping in the Black Sea. Russia responded on 1 November by declaring war on the Ottomans, with Britain and France following suit a few days later.

Gallipoli is a peninsula located at the northern edge of the Dardanelles, a narrow body of water separating Europe from Asia, both sides of which were controlled by the Ottoman Empire.

The British, spearheaded by then First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, desired to send shipping through these straits – in particular to gain access to Russia via the Black Sea – and to do so would require neutralising the Ottoman fortifications on the peninsula. Naval attacks conducted in March 1915 were unsuccessful in achieving this aim, so plans for a ground invasion were hastily drawn up.

After some delays, British, French, and Commonwealth troops landed on the northern side of the peninsula on 25 April 1915. Though they failed to capture the peninsula, the Ottomans were likewise unable to drive them back into the sea. Thereafter followed months of gruelling and inconclusive fighting in which neither side was able to make significant headway.

As a result of these failures and also because of growing need for Allied troops on other fronts, it was decided to withdraw the expeditionary force. The operation was completed in January 1916, thereby bringing the campaign to a conclusion.

Casualties from the campaign were split roughly evenly between the Allies and the Ottoman – around 50,000 men killed apiece.

Overall the campaign was a clear operational failure for the Allies, as they failed to achieve their objective of capturing the peninsula and securing safe passage through the Dardanelles. Strategically, the outcome of the campaign is less clear-cut, with several historians arguing that the invasion drained the Ottomans of men and matériel that they could replace much less easily than could the Allies, and thereby diverting their attention away from possible aggressive actions elsewhere.

In sum, the Gallipoli campaign was an important secondary campaign of the war, though far from decisive for its outcome.

I want to address three apparently common beliefs about Anzac Day which I believe are misconceptions: that Australia was a (or the) major participant at Gallipoli; that Anzac Day commemorates those who died to defend our country; and that Anzac Day is a glorification of war or crude nationalism. Then I will conclude with some reflections on what I consider to be the real purpose of Anzac Day, and the proper mode in which it ought to be observed.

‘Australia was a major participant in the Gallipoli campaign’

Australia was certainly an important participant in the campaign, but it was certainly not the largest. Of the roughly 188,000 casualties suffered by both sides, only 28,000, or about 15 per cent, were Australians. By comparison, the British suffered 120,000 casualties.

Now, of course, 28,000 casualties is a horrifically large number, particularly for a country as small as Australia. But it is, I think, important to bear in mind that the Gallipoli expedition was not predominantly an Australian affair. It was planned by the British, executed using British naval vessels, and manned mostly by British troops. Australians, as well as New Zealanders and Indians, were essentially just along for the ride, as Britain needed all the manpower it could get from its vast empire.

‘Anzac Day commemorates those who fought to defend our country’

With the possible exception of certain actions against the Japanese in World War II (and even then I think it is dubious how much of a genuine threat Japan ever posed to Australia), no Australian servicemen have ever fought in a war to defend Australia.

Australians have fought in British colonial wars (Sudan, Boer War, Boxer Rebellion, and the Malayan Emergency), in two Cold War conflicts (the Korean and Vietnam wars), in several peacekeeping operations (Somalia, East Timor), and in the Gulf War, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Not a single one of these wars was in any way in defence of Australia. These wars, whether justified or not, were all fought in the furtherance of foreign political interests, and not because Australia was under any genuine threat.

In the case of World War II, Australia was never under any threat from Germany. Australia did come under direct attack from Japan during WWII, though this was mostly limited to aerial attacks against northern cities. Despite fears at the time, realistically the threat of invasion was very low. So while there was some threat from Japan, this tends to be overstated.

The first World War, the conflict of most concern to us here, had no direct bearing on Australian security. None of the Central Powers (least of all Turkey) had any interest in Australia or an ability to exert military force over it even if the Turks did.

The only sense in which Australian involvement in World War I in any way related to the defence of Australia was via the fact that Australia’s security rested on the strength of the British Empire, which was (although, again, fairly indirectly) threatened by the war.

In the case of the Gallipoli landings, there is really no relation to Australian security at all. If anything, the invasion was about protecting British interests in Egypt and preventing the Ottomans from doing more damage to the Russians, or from aiding the Germans in fighting France and Britain in Europe.

So, in a way, Australians were dying to help defend Russia and France, albeit indirectly, and likely not very effectively.

‘Anzac Day is a glorification of war and vulgar nationalism’

Anzac Day was first celebrated by veterans as a way to solemnly remember their fallen comrades and commemorate their experiences. At first, the general public was not even allowed to join in the marches.

As far as I have been able to gather, Anzac Day waxed and waned somewhat in importance over the years, and was not a particularly prominent event even as late as the 1970s. Its current popularity with many young people and concomitant association with a certain brand of frenzied Australian nationalism seems to date to the 1980s and 1990s.

Thus, if people feel like Anzac Day glorifies war or encourages a particularly distasteful form of nationalism, we should not assume this is something intrinsic to the commemoration itself. Rather, it is due to the way the day has come to be seen and experienced by a certain group of people.

Rather than saying Anzac Day is those things, I think it is more accurate to say that Anzac Day has been – or can be to varying degrees in varying circumstances – co-opted for such uses, and that when this happens the real spirit and meaning of the day is lost.

I find it particularly odd when people make the claim that the solemn marches, minutes of silence, sounding of the last post, reading of commemorative stories and poems, etc, in any way constitutes a ‘celebration’ or ‘glorification’ of war or militarism. To commemorate something is not to celebrate it. If people are incapable of understanding the difference, this is a fault of their ignorance, not of Anzac Day itself.

Misplaced attitudes or expectations regarding what Anzac Day is and what it is for can and should be corrected by communication and proper social modelling of how to conduct a respectful commemoration without turning it into crass celebration. I think this would be a far more productive response than demonising the day altogether, as some have tended to do.

Some thoughts

I think it is good and proper to have a national day to commemorate those who fought and died in war. I do not see any need for this to be linked in any particular way to nationalism or to contemporary military or political issues. It is not necessary that those we commemorate fought for a righteous cause, or even for any cause at all.

In this respect, I think we should be reflective and honest about Australia’s military history, which I think is mixed at best. Australians like to think that Australian soldiers fought and died to protect freedom and liberty, and arguably Australia has done this some of the time (e.g. World War II, the Korean War, the Gulf War). In many other cases, including that of Gallipoli, the rightness of the cause for which Australian soldiers fought is much less clear.

Indeed, in the case of the Gallipoli campaign, I would go further and say that there was no clear cause being fought for. Moreover, whatever the cause, the Gallipoli campaign was a failure – the invasion was not successful and the soldiers were eventually evacuated. It was a pathetic waste of human life, which achieved little or nothing to advance our interests, all in support of a war that had no real purpose to begin with.

Is this something we should celebrate? Glorify? Sanitise? Absolutely not. Is it something that we should remember? Commemorate? Reflect upon? Absolutely.

Anzac Day, correctly understood and commemorated appropriately, is exceptionally important. It is a day to remember those who fought and died, for Australia and for other countries, for causes good and bad. They were, most of them, ordinary men and women who, for various reasons, found themselves in horrific circumstances. They fought, they suffered, and they died. They were just people like you and me. They don’t have to have died for a noble cause in order for their lives and experiences to be worthy of our commemoration.

Anzac Day is also a day when we should reflect on the past. We should celebrate those occasions when brave men and women stood up against injustice or tyranny, and at times gave their lives so that we may live in peace and security. Romanticised as it may sound, I believe this has happened on occasion in Australian military history, and is certainly worthy of remembering and celebrating.

We should also reflectively consider the times when war was fought because of greed, cruelty, intolerance, or even for no clear reason at all. We must try to remember and learn from these experiences so that we can grow as individuals, as a nation, and as a species, and learn to live with each other in greater peace and harmony.

Forgetting the mistakes of the past and not taking time to reflect upon them will not help us to achieve this vital goal. This, in my view, is one of the most important purposes of Anzac Day.

I’ll close with a few words from one of my favourite commemorative songs:

There is no enemy

There is no victory

Only boys who lost their lives in the sand

Young men were sacrificed

Their names are carved in stone and kept alive

and forever we will honour the memory of them

And they knew they would die

Gallipoli

Such waste of life

Gallipoli

Have a commemorative, thoughtful, reflective Anzac Day. Lest we forget.

This article has been republished with the permission of the author. It originally appeared on his blog.

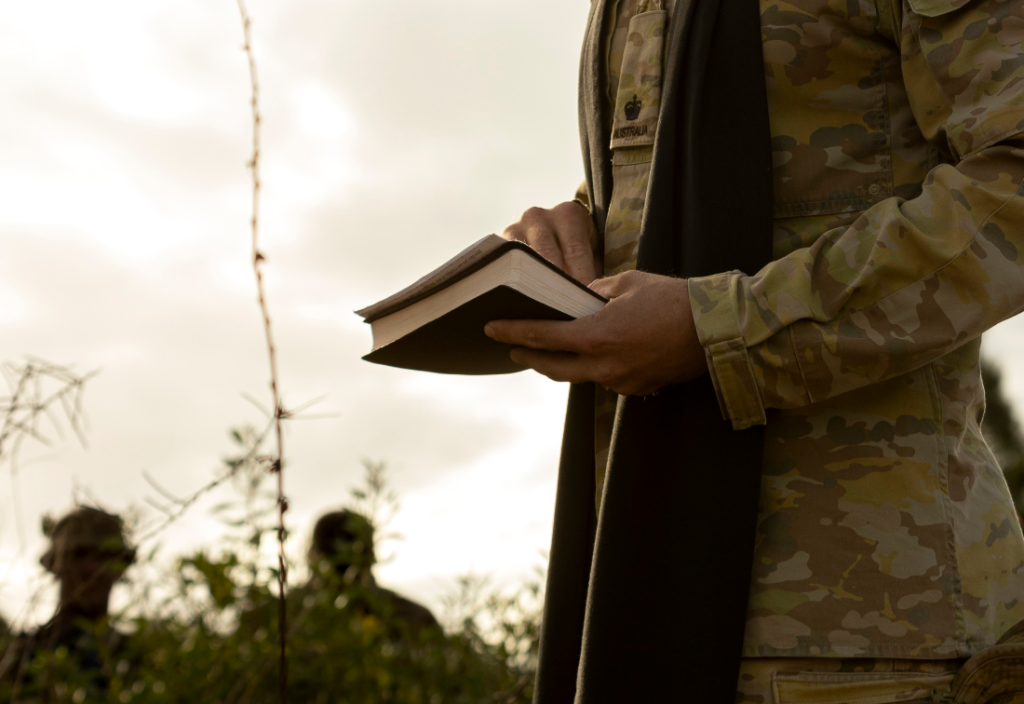

Photo by Troy Mortier on Unsplash.

What a great article. We’ll done James. I hope it gets reprinted in one of the main mastheads.