The question of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament in Australia is fundamentally an ethical matter, though opponents often frame it in political or legal terms to avoid facing the moral issue.

Australia’s colonial history has resulted in the disenfranchisement of its original inhabitants – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders – by taking their lands without consent. The ethical solution, since returning the land is impractical, is to compensate and give a voice to the original possessors.

Critics who label the Voice as “divisive” miss the point. Australia is already a diverse society that accommodates various needs through different policy frameworks. Refusing the Voice on grounds of divisiveness is not just hypocritical but avoids the primary ethical obligation towards the original inhabitants.

While opponents argue that it would separate Australians into two groups, this argument falls apart when one considers existing societal divisions that we accept for the sake of justice, such as support mechanisms for the disabled through the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

The Indigenous proposal for reconciliation does not demand land or monetary reparations but seeks political inclusion through a constitutionally recognised Voice to Parliament. This aligns with consultations and recommendations from the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart, which emerged from the Referendum Council set up by the previous coalition government in 2015.

The notion that the Voice is paternalistic or exclusive has been discredited, as it arises from negotiation of just terms with Indigenous peoples, not a predetermined solution imposed by Canberra.

Those opposing the Voice often shift the discussion to potential negative consequences of its implementation, without giving due weight to the disastrous implications of a ‘No’ vote, including setting back reconciliation efforts for decades.

Ethicist Professor Margaret Somerville argues that the moral case for a ‘Yes’ vote is so compelling that potential risks should be considered secondary, to be mitigated during the implementation process.

The ethical argument for supporting the Voice is persuasive, and attempts to undermine it often involve red herrings that avoid the central ethical issue. Ignoring this ethical case is, in itself, an immoral act.

The arguments for voting ‘No’ in the upcoming referendum are based on historical amnesia and unfounded apprehensions, which require thoughtful examination for a clear perspective.

Dissecting the ‘No’ case

W.E. H. Stanner’s seminal observation of “the Great Australian Silence” 55 years ago is still alive in the ‘No’ case – a systemic blind spot for our colonial past. Notably, the official ‘No’ case document avoids this crucial issue altogether. Rather than outright denial, it’s a case of selective ignorance or historical whitewashing.

Professor Ramesh Thakur’s op-ed in The Australian embodied this disconnect. In the article, he lauds modern Australia’s multiculturalism and equality, apparently unaware that these ideals are recent additions to our national narrative.

The Australian Natives’ Association, a driving force behind 19th-century Australian society, was an exclusive club for white, Australian-born males. It was this mindset that led to an Australian Constitution explicitly excluding Aboriginal people and spawned the discriminatory White Australia Policy in 1901 – legislation that would have barred Professor Thakur himself, who is of Indian descent.

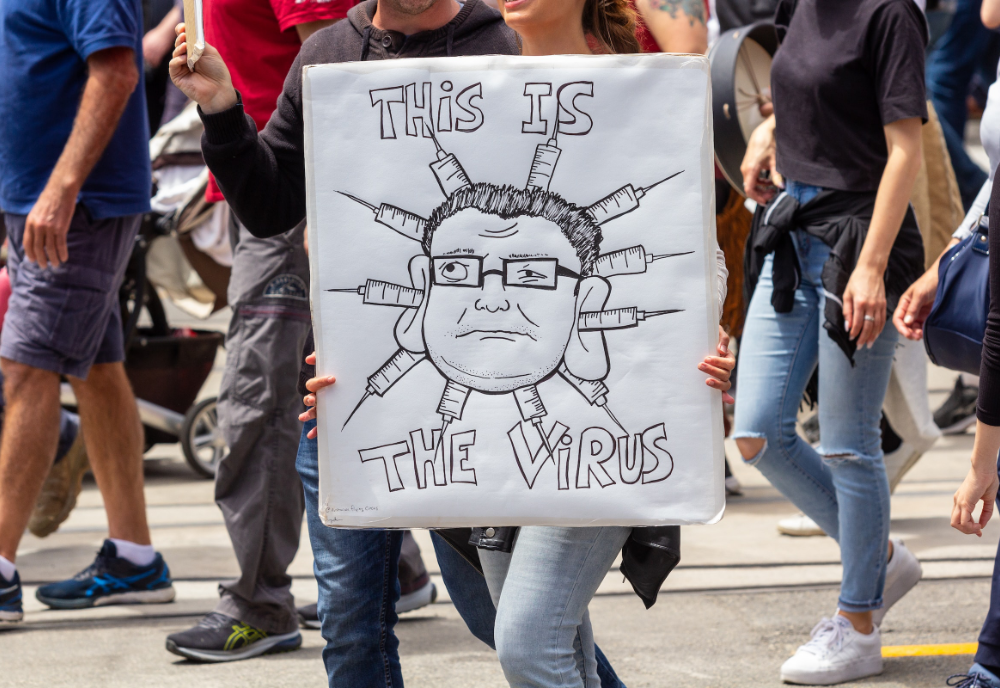

While Australia has made strides toward inclusion, remnants of that old racist and bigoted spirit persist, even gaining new momentum with the rise of ultra-Right-wing movements. These views contribute to the ‘No’ vote.

The ‘No’ case overlooks the unique rights Indigenous people should have as original inhabitants and survivors of historical injustices, treating them as just another part of our multicultural fabric. Ignoring these issues isn’t just historical neglect; it’s a moral failing that undermines the validity of the ‘No’ case. To move forward, we must confront our past, not erase it.

The amendment proposes that a new Chapter IX titled “Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples” would be added to the Constitution. It would contain one new section, Section 129, named “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice,” which would be the first and, initially, the only section in this new Chapter.

The preamble explicitly states that the rationale of the new section is the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia – thus making it clear that the Voice is not based on their race but on their status as original inhabitants.

There are three subsections proposed. Subsection 1 legally establishes a body called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Subsection 2 states that the new body can make representations to the parliament and the executive government on matters specifically related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. And subsection 3 grants the parliament the power to legislate all the details concerning the Voice, such as its composition, functions and procedures.

The assertion that the amendment is “racist” because it provides a voice based on race is a distortion. The Voice is not based on race but on the status of being the First Peoples. To claim that setting up the Voice is racist is like claiming that the freeing of the slaves in the United States of America was a racist act because it only applied to people of one race, Black Africans. Equating this with racism distorts the very purpose of the amendment and strays into intellectual dishonesty.

Some argue that establishing an Indigenous ‘Voice’ in the Constitution creates a form of sacred permanency. This is misleading. Constitutional amendments, by their nature, can be undone through subsequent referenda.

The aim is to secure this advisory body from the political whims that have undermined past Indigenous consultative bodies. The ‘Voice’ would serve a precise but limited function: making representations to the parliament and executive government, devoid of legislative power.

The aim is to secure this advisory body from the political whims that have undermined past Indigenous consultative bodies.

Claims that the Voice will have significant power or authority are unfounded. The body is advisory and can only make representations. Concerns that the Voice would involve itself in all aspects of Australian life are exaggerated. The mandate is very specific to issues related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Ironically, as well as arguing it will have too much power, opponents also argue it will not have enough power to materially help Indigenous peoples. This fails to understand that its function is not to directly improve Indigenous conditions itself, but to ensure that government does, through being better informed and advised.

Two main arguments question the extent of the Voice’s influence. The first argument suggests restricting the Voice’s advisory role just to the parliament, overlooking the fact that most policy-making occurs in the executive branch, which could also benefit from Indigenous perspectives.

The second argument contends that the Voice could broadly interfere in Australian life – a claim based on a misconstrued understanding of the phrase “matters relating to”. This misunderstanding suggests that the Voice would have a say in almost every aspect of Australian politics and life.

However, the term “relating to” specifically means issues that are concerned with or connected to Indigenous Australians. General policies that impact all Australians are not thereby Indigenous issues. For example, no one would argue that Stamp Duty, which affects all Australians equally, is thus a “matter relating to” naturalised Australians, or people with beards, even though they are affected by it.

This argument erroneously amplifies the scope and purpose of the Voice, creating an unfounded fear that it could interfere in all aspects of Australian life. Both arguments misrepresent the intended scope and influence of the Voice.

The words of the amendment are clear: the final authority over the Indigenous Voice will reside with parliament, reflecting the democratic will of the voters. Therefore, any concerns about the Voice gaining unwarranted control are baseless. The fears and objections surrounding the proposed constitutional amendment are marred by historical oversight and misinterpretation. These arguments not only underestimate the institutional checks in place but also overlook the tangible benefits the Voice aims to bring to Indigenous Australians. Voting ‘No’ based on these shaky premises would be a disservice to the spirit of informed democracy.

Untruths, ignorance and fear of the unknown

In the ongoing debate surrounding the proposed Voice to the Australian Parliament, some critics have put forth arguments that are misinformed, misleading, or rooted in unfounded concerns. Here we dissect the most notable ones.

The ‘No’ case contends that the proposed Voice represents an unprecedented alteration to our Constitution and poses a dire threat to our system of government. However, this claim overlooks significant past amendments, such as the 1967 referendum that allowed Indigenous Australians to be counted in the Census, or the 1946 social services referendum that fundamentally expanded the Commonwealth’s role in social welfare. Both changes had far-reaching impacts and demonstrate that the Constitution is not immutable.

Legal experts, including Barrister Liz Bennett SC and Laureate Professor Emeritus Cheryl Saunders AO, have refuted the claims that the Voice would undermine the functioning of our government institutions. These notions were convincingly dispelled in a seminar at the University of Melbourne. Professor Saunders emphasised that the Voice is designed to function primarily through political mechanisms rather than legal battles. Bennett laid out the complexities of bringing a High Court challenge against the Voice, effectively dismissing fears of a legal quagmire.

Another persistent yet unfounded criticism is that there is a lack of detail about the principles of how the Voice would function. This ignores the comprehensive 275-page Calma/Langton report sponsored by the previous coalition government, and the Voice Design Principles released by the First Nations Referendum Working Group set up by the current government.

Designed as an advisory body, the Voice would furnish counsel to the parliament and executive on matters affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Its structure aims to be genuinely representative, with elected members and a commitment to gender balance. Importantly, one of the Australian government’s released principles for the Voice is that Voice members would fall within the scope of the National Anti-Corruption Commission.

The claim that the Voice’s blueprint is vague is not just intellectually insincere but ethically questionable. It diverts attention from the crux of the matter: the ethical need to rectify historical disenfranchisement of Indigenous communities. Detail exists, and it is substantive.

It must be emphasised that critics of the Voice often resort to deliberate untruths or ignorance, muddying a debate of profound national significance. These arguments should be recognised for what they are – diversions from the actual issues at stake. It’s time to move the discourse beyond these distractions and focus on the ethical imperatives that necessitate the Voice.

The notion that establishing an Indigenous Voice to parliament is fraught with legal risks and uncertainties has been touted as a critical argument against the initiative. While it is true that such an institution hasn’t been ‘road-tested’, this doesn’t necessarily portend a legal quagmire. Critics like Professor Thakur and Kevin Donnelly posit that the Voice would hamper effective governance and balloon into a costly bureaucracy. Yet constitutional law expert Professor Anne Twomey suggests that the financial implications of the Voice would be minimal, as it would operate as a consultative body.

The claim that the Voice’s blueprint is vague is not just intellectually insincere but ethically questionable.

Concerns about disrupting governance are alarmist at best. It’s worth noting that any new governmental institution carries inherent uncertainties. However, to let that alone be the deterrent would mean shying away from bold initiatives that could be transformative for society. The Voice would serve as a mechanism to make government bureaucracies more accountable, especially in matters affecting Indigenous communities—a point underscored by the Productivity Commission’s review on Closing the Gap.

Critics also argue that the government’s reticence to disclose the legislative plans for the Voice is an admission of some concealed agenda. However, history shows that detailed plans are seldom released before referenda in Australia. None of the eight successful amendments to the Constitution so far had detailed legislation presented for approval at the same time as the vote.

The lack of specifics, critics claim, masks the extremism of some activists. But an alternative interpretation sees it as an opportunity for First Nations and the government to negotiate the finer details in a transparent manner, rather than imposing a rigid structure from the outset. Mark Gleeson posits that not establishing the Voice could deepen societal divisions, leaving us with an unresolved issue that could grow more contentious over time.

Moving to Professor Thakur’s argument based on the “ethics of conviction” and “consequences”, it’s important to differentiate the two. The ethics of conviction focuses on sticking to one’s moral or ethical principles, irrespective of the outcomes. Consequentialism, meanwhile, judges actions solely based on their outcomes. Professor Thakur claims the Voice lacks both ethical and practical merit, as it doesn’t directly improve metrics like life expectancy or literacy in remote communities. However, this view falls short because it sidesteps the Voice’s potential role in effecting systemic change.

Professor Thakur’s argument employs ethical jargon to cloak political opposition, and this essay offers sufficient evidence to dispute his foundational claims. What we are witnessing is less an earnest debate on the utility and feasibility of the Voice, and more an exercise in divisive politics.

The stakes are high and, as the rhetoric escalates, we risk losing sight of the ultimate aim – that is, to give Indigenous communities a meaningful say in the decisions that affect them. Let’s not allow polemics to deter us from an initiative that could be pivotal for Australian democracy.

The urgent need for Indigenous voices to be heard

The Voice is not a mere talking point; it is an institutional vehicle designed to amplify the perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities within the Australian political ecosystem. Comprised of Indigenous Australians from diverse regions, the committee will provide informed advice to the government and parliament. Members will be locally elected for fixed terms, thus ensuring democratic legitimacy and representative efficacy.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart is far more than an appeal; it is an elegant blueprint for justice and co-existence. It acknowledges the unbroken, one-thousand-generation sovereignty of Indigenous tribes and emphasises the need for constitutional reforms. Beyond mere articulation of grievances, the statement’s tone is of aspiration, collaboration and empowered solutions. It puts forth constitutional reforms that aim for both truth-telling and agreement-making through a Makarrata Commission.

Andrew Gleeson describes the Uluru Statement from the Heart as both temperate and poignant, seeking reconciliation rather than making demands. The statement recognises the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes as Australia’s first sovereign nations, having a spiritual and legal bond with the land for over 60 thousand years. It calls for constitutional reforms like a First Nations Voice and a Makarrata Commission, aimed at truth-telling and agreement-making.

The statement highlights the painful reality of Indigenous incarceration, stating: “We are the most incarcerated people on the planet.” It identifies the root issue as structural, describing it as “the torment of our powerlessness”. Yet, it also offers a way forward: constitutional reforms to empower Indigenous communities, promising a future where their children will thrive. These are not words of a people trying to avoid accountability.

In a democratic system that often sidelines minorities, the Uluru Statement from the Heart offers a blueprint for a more equitable Australia. If effectively implemented, the Voice could address the inequalities tearing at the fabric of democracies worldwide. The Makarrata concept encapsulates the aspiration for a just and honest relationship between First Nations and the broader Australian community.

Before casting your vote in this referendum, we urge you to read the one-page Uluru Statement and consider its profound implications for justice and self-determination in Australia.

Australian democracy, while robust, is not immune to the pitfalls of majoritarian rule, especially when it tends to marginalise minority voices. The Voice is proposed as an evolutionary step in democracy – one underpinned by checks and balances to preclude abuses of power. Given that the parliament has the mandate to fine-tune the Voice’s design, concerns about its operational viability should be allayed.

Incorporating the Voice into the Constitution offers substantive recognition to our Indigenous people, but this type of body is also a democratic innovation. With the parliament holding full authority to legislate its design and function, such a body would not be a threat but a complement to our democracy.

The potential impact of a well-executed Voice cannot be overstated. Legal scholars such as Anne Twomey have noted that well-designed Indigenous bodies in other countries have improved governance and social outcomes. It could be a ground-breaking addition to our democratic system, providing representation for those often unheard.

In a political landscape where mining companies, big business, and major unions already have influential platforms, the Voice could act as an equaliser, enhancing our democracy by broadening representation. If successfully implemented and iteratively improved, the Voice could serve as a model for providing platforms to other marginalised communities, thereby improving the inclusiveness and, consequently, the quality of our democratic discourse.

The path forward

An enterprise is only as robust as its weakest part, and the same is true for governance. The dismal progress in Closing the Gap strategies underscores the urgency of heeding Indigenous perspectives. The Voice aims to make such active listening systemic. Critics argue that this is already happening, but they miss the point. The Uluru Statement from the Heart proposes a more organised, Indigenous-driven model of feedback, thereby shifting the axis of control toward those who are most directly affected.

Indigenous Australians face staggering challenges. They experience an eight-year shorter life expectancy, elevated rates of disease and infant mortality, disproportionately high levels of violence against women, a suicide rate twice that of non-Indigenous Australians, limited educational opportunities, and a 14-times higher imprisonment rate. It’s patently obvious that the current approach is failing.

Contrary to claims that sufficient consultation already exists, the Uluru Statement from the Heart calls for a systemic shift – not mere talks but a guarantee that Indigenous voices will be heard and will shape their own solutions. This is not about Canberra dictating terms; it’s about empowering Indigenous communities to drive their own futures.

Adopting their proposal for a Voice allows Indigenous communities to not just recommend solutions but take responsibility for them, holding them accountable for the outcomes. It’s high time we listen, empower, and hold accountable all participants engaged in the implementation of these policies.

The official recommendations for constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians are neither superficial gestures nor mere amendments. They aim to correct historical injustices by empowering Indigenous communities in a meaningful way, lending their unique status the dignity it deserves. And all of this without diminishing the parliament’s legislative sovereignty.

The Voice is not just about redressing past wrongs but about forging a future of economic and social integration. It aligns with the Australian ethos of mateship and equality, aiming to elevate Indigenous contributions to national character. By adopting the Voice, Australia has an opportunity to set a global example of an egalitarian society that genuinely respects its historical and cultural pluralism.

The Voice serves multiple functions: it is an instrument of justice, a safeguard of democratic integrity, and a catalyst for social and economic renewal. By saying ‘Yes’ to the Voice, Australia will make a significant move towards unity, democracy, and shared prosperity. It’s not just a constitutional addition; it’s an evolution of Australian identity and governance.

Thus, before casting a vote in this referendum, one should not just skim but ponder the Uluru Statement. In its lines lie not just the past and the present but also the promise of a more inclusive, empowered, and harmonious future.

This article is co-authored by Ian Robinson, President Emeritus of the Rationalist Society of Australia.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Matt Hrkac on Flickr (CC)