The official No case for the Voice referendum – the pamphlet of which has just been published by the Australian Electoral Commission – reminds one of the old joke about a camel being a horse designed by a committee.

The document is nothing more than a farrago of vague epithets, patent untruths, unfounded fears, baseless claims, wild speculations and the same arguments repeated a number of times in slightly different language, as though the authors had run out of things to say.

Running through the whole document is a strong streak of neophobia – an irrational fear of anything new or different.

After a short summary, which briefly outlines the scariest four of its eventual 10 arguments, the document launches into what it claims are ‘Ten Reasons to Vote No’. None of them stands up to serious scrutiny.

Let us deal with each purported reason in turn.

1. ‘This voice is legally risky’

Their case begins with a truism: “Australia’s Constitution is our most important legal document”. It then adds, “Every word can be open to interpretation”, implying that this is a reason not to alter it. This is nonsense.

The Constitution is 125 years old. It would be ridiculous to suppose that every word of it was still fit for purpose after all the changes that have occurred in society and all the new insights we have gained over that time.

The fact that every word can be open to interpretation is not a reason to never change it; it is simply a reason to choose your words very carefully when you do need to make changes.

In the case of the Voice amendment, the wording went through an intensive editing process in which both parliamentarians and legal experts scrutinised it in great depth before it was finalised and passed through parliament.

The No case then lurches into tired old clichés calculated to make us wary: “It is a leap into the unknown.” “This Voice has not been road tested.” “This opens a legal can of worms.” The resort to such vague metaphors indicates a failure to connect with the salient facts of the situation.

Yes, the amendment is new – that’s what ‘amendment’ means – but to call it a leap is a bit of an exaggeration. It’s just a Voice which can “make representations”.

By definition, changes to the Constitution can’t be “road tested”. We don’t know how a new clause in the Constitution will function as part of the Constitution until it is actually in the Constitution. There’s no mock politico-legal arena in which proposed new constitutional clauses can be run through their paces. All we can do to ensure they function as we intend is to be very meticulous in the drafting process.

Of course “[e]nshrining a Voice in the Constitution” does mean “it is open to legal challenge and interpretation by the High Court”, but it is hard to see what legal challenges might be made.

The only aspects of the Voice that are actually enshrined in the Constitution are its existence: “There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice” and its ability to “make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government”.

Every other aspect of it, including, specifically, its “composition, functions, powers and procedures” are in the purview of Parliament.

In other words, most aspects of the implementation and operation of the Voice are not enshrined in the Constitution and, therefore, not subject to legal challenge and interpretation by the High Court.

The No case quotes legal expert and former High Court Judge Ian Callinan AC KC as saying: “I would foresee a decade or more of constitutional and administrative law litigation arising out of a voice …”. However, this is a general comment about the generic concept of a Voice made back in 2022 and not a considered legal opinion based on perusing the actual proposed amendment.

Professor Paula Gerber and Lecturer Katie O’Bryan of the Faculty of Law at Monash University, who have studied the actual amendment, write on the university’s website:

“How Parliament responds (or does not respond) to any representations made by the Voice would be non-justiciable – that is, it could not be subject to any court challenge. This is because the courts have always been reluctant to interfere with the internal workings of Parliament.”

So it sounds like there’s nothing to see here. The spectre of lots of High Court challenges and endless litigation has no substance. It’s just put out there to provoke anxiety and uncertainty.

Finally, in this section there is the extraordinary claim that granting Indigenous Australians the modest right to “make representations” would be “the biggest change to our democracy in Australia’s history”.

Really? Bigger than votes for women? Bigger than compulsory voting? Bigger than proportional representation? Bigger than Aborigines getting the right to vote? Bigger than Federation itself? Tell them they’re dreaming.

2. ‘There are no details’

“You wouldn’t buy a house without inspecting it or a car without test driving it. Yet you are being asked to vote to change our Constitution without details. Australians shouldn’t be asked to sign a blank cheque.”

More irrelevant, misleading and misplaced metaphors.

The fact that this phony complaint is being advanced here by politicians and political players who know how the system works shows how disingenuous the No case document really is. These people know that the Constitution is not where details are set out. The Constitution sets out the principles, then parliament works out the details.

It won’t be easy setting up the Voice; it may be a trial-and-error process. So parliament will need wriggle room, the ability to make later changes and fine tune along the way. Too much detail set in concrete before the Constitutional change would handicap and hamstring the implementation process later on.

Having said that, it’s worth noting that the proposed new Section 129 in the Constitution does contain more detail than most sections. Out of the 128 existing sections, only 14 are actually longer, containing more detail than the proposed new Voice one.

Moreover, anyone who does feel the need for more detail can read the Design Principles for the Voice, published by the Government and the 270-page Calma/Langton report, commissioned by and received by the same people who co-wrote the No case document and who are now whining about ‘no detail’!

But, as we explained, such detail is incidental to the amendment, and not what we are voting on.

3. ‘It divides us’

We try to pretend otherwise but our ‘exemplary’ Australian Constitution already potentially divides us – and, what is more, on the basis of race. Section 51, subsection xxvi, gives parliament the power to make laws with respect to, “The people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws.”

For some time, most Australians have realised that we do need to make special laws in relation to our Indigenous people in recognition of their de facto prior sovereignty of the continent (which was acknowledged by the Mabo ruling), as part of a process of reconciliation.

For this reason, in 2015 then coalition Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull set up a Referendum Council to advise the government on steps towards a referendum to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Australian Constitution.

The council spent six months travelling to 12 different locations around Australia. They consulted with over 1200 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives. In 2017, a First Nations National Constitutional Convention met at Uluru and the 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates voted to support the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which asked for an Indigenous Voice, a truth-telling process and a treaty.

Since the very same coalition politicians who have now co-written the official No case document originally invited the Indigenous people to come up with a proposal to facilitate Indigenous constitutional recognition, it is a bit rich for them to turn around and label such a proposition ‘divisive’.

The truth is that Australians are already divided into different legal categories for all sorts of rational purposes – children and adults, male and female, abled and disabled, licensed to drive a vehicle and not licensed to drive, qualified to practise medicine and not qualified, to name a few. All these result in different treatment under the law. And we also create and even celebrate many other internal divisions that are a matter of choice – football team, political party, religious affiliation, and so on.

While we may be undivided in our loyalty to our nation and in our commitment to the rule of law, we are in fact divided in so many other ways, some necessary, some questionable. So being ‘divisive’ per se is clearly not the issue. The real question is: if the Voice does divide Australians in any way, does it do so fairly and for ethically and politically justified reasons and purposes? In other words, is the Voice equitable?

The Constitutional Expert Group set up to examine the amendment and comprising nine experts (including former High Court judge Kenneth Hayne), and chaired by the Commonwealth Attorney-General, has determined that an Indigenous Voice will not give Indigenous peoples special rights.

All Australians now have, and will retain, the right to make representations to parliament, which is guaranteed by the constitutionally implied freedom of political communication. Anyone can approach their local member of parliament. If you are a member of an organisation, either they or their peak body will probably have a lobby group in Canberra. Think of the Mining Council, the Australian Christian Lobby, the Australian Council of Commerce and Industry, the Australian Council of Trade Unions, and so on.

The only difference in the case of the Voice is that its actual existence would be mandated in the Constitution, and the Constitution would empower it to “make representations”. This would simply mean there would be an expectation that parliament and government would listen to what they have to say.

But, importantly, this wouldn’t mean that they have to do what they say. Being ‘enshrined’ in the Constitution would not automatically transform an opinion into an instruction.

The reason Indigenous people wanted the existence of their Voice mandated in the Constitution was to insulate it from the vagaries and whims of future politics. In the past, there has been a long procession of Indigenous ‘voices’ set up by one government, then dismantled and replaced by the next. If the Voice were in the Constitution, it could only be removed by another referendum.

But it is important to reiterate that it would only be its existence and its function of making representations to parliament and government that would be enshrined in the Constitution. As we noted above, every other aspect of the Voice, including, specifically, its “composition, functions, powers and procedures” would be in the purview of parliament, which would be the only body that the proposed constitutional amendment specifically would give any power to.

It is also important to emphasise that the Voice is not about race. The Indigenous people are getting a Voice because of their prior de facto sovereignty of the continent, not because of their race. It’s an accident of history that the people who were living here when Great Britain annexed the continent were all members of the same race. But it’s their prior possession, not their race, that gives them the right to a Voice.

The Voice is part of a long process of recognition and reconciliation by the descendants of the settlers who acquired this continent without the consent of the existing inhabitants. Accepting and embracing it can only serve to unite us all in a common process which is both benevolent and nation-building. It is those who oppose this reconciliation process and the Voice who are being divisive.

4. ‘It won’t help indigenous Australians’

This section begins:

“We all want to help Indigenous Australians in disadvantaged communities, to close the gap and achieve reconciliation”.

But this is simply not true.

I recently received an email dismissing our Indigenous people as “marauding, nomadic, lawless tribes, continually fighting with each other”. It described measures to Close the Gap as ‘Racist Aid’ that is “taking money from poor non-Aboriginal Australians and giving it to rich Aboriginals”, and complaining that “the loudest proponents of the Voice referendum are the Aboriginal Industry, as they mill around seeing the pocket-lining millions they can suck out of our taxes.”

This person is not an original thinker, so I am sure he or she got these ideas from the internet and that there are many other people out there with similar views. They form a significant proportion of those planning to vote No.

There are many well-intentioned people in the No camp but they can’t avoid the uncomfortable truth that by progressing the No campaign they are ipso facto progressing the agenda of the extreme racists in this country, whose numbers seem to be growing. That should give them pause.

Meanwhile, while the Voice will not, and is not intended to, solve every problem confronting Indigenous people in Australia today, its impact will not be insignificant.

Since the Voice will provide advice to the parliament and executive government on proposed laws and actions affecting Indigenous peoples, they will both be better-informed about the impact of proposed laws on the latter.

Having a better-informed parliament and executive is more likely to lead to better laws and more appropriate government action than not, and that must have a positive impact on Indigenous lives. How can this not help Indigenous Australians?

But the No case is right to draw attention to some of the dangers and traps involved: “A centralised Voice risks overlooking the needs of regional and remote communities”; and “more bureaucracy is not the answer”.

Once the amendment is passed, parliament will need to make sure that the Voice is up to the task of listening, as the No pamphlet says, to the “many voices … crying out for help in tackling devastating social problems in … remote communities” and ensuring that it doesn’t just become a huge new bureaucratic nightmare.

But these caveats are not per se reasons to vote against the Voice. Rather they are reasons for extreme vigilance and ingenuity during the difficult process of actually putting the Voice into practice.

5. ‘No issue is beyond its scope’

The No case points out:

“This Voice model isn’t just to the Parliament, it goes much further – to all areas of ‘Executive Government’. That includes all government departments, agencies and other bodies (like the Reserve Bank).”

Some have argued that the Voice should not be able to make representations to executive government, and only to parliament. But, in fact, very little of the work of governance is done by parliament, which simply makes the laws which set the goals and parameters. It is when these laws are executed, put into practice by the executive government and government departments, they start to have an impact on us. So it would seem to be wise to give the Voice the opportunity to make representations at this level, too.

Furthermore, the No case worries that “[d]ecisions in relation to the economy, national security, infrastructure, health, education and more, would all be within [the Voice’s] scope.”

This revolves around the meaning of the phrase “relating to” which may be narrowly interpreted to mean “matters relating only to Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples”. Even if “relating to” is interpreted more broadly, this is not necessarily a bad thing. Why shouldn’t the Voice make representations about how tax laws, for example, might affect the Indigenous population? Representations are not decrees or mandates; they are only opinions to be accepted or not.

We mustn’t discount the possibility that we might actually learn from the Indigenous perspective on many so-called ‘non-Indigenous’ issues. For example, if we had had an Indigenous Voice in the original 1901 Constitution, and had been able to listen to the Indigenous views on land management and bushfire control, we might have saved many hundreds of lives and many thousands of hectares of bushland from such fires.

If we had been able to listen to an Indigenous Voice on water management, we might have avoided the Murray-Darling Basin disaster. If we had listened to the Indigenous Voice on the environment, we might have prevented the extinction of some of the 99 plant and animal species that we’ve eliminated from the continent and the planet since we arrived here.

Behind a lot of this concern about the scope of the Voice lies an inflated conception of the power of the Voice and the fear that Indigenous people will use it to start throwing their weight around. It must be emphasised once again: the Voice can’t do anything; it can only say things. While the conclusion of the old adage “words can never hurt me” is not entirely true, in a political context words are flying everywhere, and a few more of them are really neither here nor there. There is nothing to be afraid of here.

6. ‘It risks delays and dysfunction’

This reason is essentially a rerun of the first reason, although with the addition of a time factor:

“If the Voice is not satisfied with the way it has been consulted, or a decision that is made, it could appeal to the courts. How long would this take?”

Moreover:

“The Australian Parliament deals with hundreds of pieces of legislation a year. … How would the Voice handle this?”

The No case worries that “this would cause considerable delays in decision making”. Again, this is not really an argument about the principle of a Voice, just a worry about how it might work out in practice if it was badly handled.

But such inefficiency is not inevitable, so this is really an argument for making sure the Voice is well-designed and fit for purpose. Voters who are exercised by the possibility of failure here might find some comfort in the Design Principles mentioned in the second reason above.

While there are a handful of alarmists, most experts believe the Voice can function very efficiently if it is sensitively designed.

7. ‘It opens the door for activists’

Another metaphorical cliché, but what does it mean? In this context, it seems to mean that, if voted in, the Voice will allow activists to have access to something that they didn’t previously have access to.

First, a word about ‘activists’. Strictly speaking, the people who wrote the No pamphlet and who are, therefore, active in support of that No campaign are ‘activists’. But since this is a No campaign document, they cannot be ‘activists’ that the No case wants to close the door to.

It turns out there are two lots of undesirable activists that might sneak in through the gap that the Voice will open up for them.

First, there are the activists proselytising the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which asked for three things – a Voice, a truth-telling process and a treaty or treaties. The No case implies that, to misquote Shelley, if the Voice comes, then can truth-telling and treaties be far behind?

According to the No case, this would be a dangerous outcome:

“A member of the Government’s Referendum Working Group has described ‘truth’ as ‘leverage’ to lead to ‘the abolishment [sic] of the old colonial institutions’.”

And not just that. Back in 2020, a prominent Voice supporter said:

“[The Voice] is a way to further what we need for our people in any negotiations for treaties…”

The implication is that because we don’t want truth or treaty we need to head them off at the pass – sorry, the Voice.

One can understand why a group that habitually uses untruth as leverage might recoil from the prospect of the use of truth for the same purpose, but what’s wrong with a treaty? It turns out, according to the No case, that the Indigenous people can’t have a treaty by definition.

According to the No case: “By definition, a treaty is an agreement between governments” and the Indigenous people are merely “one group of citizens”. But they haven’t done their homework. That is, indeed, more or less the first definition of ‘treaty’ given by the Macquarie Dictionary. But if the No case had bothered to read down further they would have come to the third definition: “any agreement or compact”.

So there is no linguistic impediment to the First Nations negotiating a treaty with the Australian government.

But that’s not the worst of it. According to the No case:

“Already, many activists are campaigning to abolish Australia Day, change our flag and other institutions and symbols important to Australians.”

They neglect to mention that there are also many activists campaigning to retain all those things.

The problem is, says the No case, that: “[i]f there is a constitutionally enshrined Voice, these calls would grow louder”, which would lead to irreparable harm to Australian society.

Two things need to be said here. First, while it is possible some ‘activists’ with agendas that the No case group doesn’t like may use the Voice to promote their cause, if the No vote succeeds they won’t just go away. They will use the No vote as evidence to further support their radical arguments against “the old colonial institutions”. So a No vote in the referendum would be playing into these activist’s hands.

Second, some radical ‘activists’ are actually campaigning for a No vote, too, partly because they can then use it to show how racist Australia is and, thus, attract more followers to their cause.

So the irony is that while there’s a slight risk a Yes vote might “open the door” for a few moderate ‘activists’, a No vote would “open [an even bigger] door” to many more much more radical ‘activists’. The conservatives in the No camp seem to be totally blind to this eventuality.

Moreover, lurking behind this No case argument is a disturbing anti-free speech sentiment. Many people in this camp want to limit the views of those they don’t agree with.

8. ‘It will be costly and bureaucratic’

There is no doubt the introduction of the Voice would incur a cost, as any new initiative would. And there is no doubt there would need to be some bureaucracy established.

However, to advance this as a reason to vote No is absurd. If a government didn’t do anything new if there was a cost and it involved hiring public servants, nothing would ever be done.

The trick is to design the Voice and implement it at minimum cost and with minimum bureaucracy.

If we don’t succeed in this, we will only have ourselves to blame, because we elect parliament and, according to the proposed amendment, parliament is the only body that has “power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures”. The future is in our hands.

9. ‘This Voice will be permanent’

“Once it is in the Constitution it won’t be undone.”

This is another furphy. If something is voted into the Constitution, it can be voted out of it.

Historically, of course, it has been notoriously difficult to amend the Australian Constitution. But, of the eight changes to the Constitution that have been made so far, five of them (63 per cent) have involved deletions of, or alterations to, existing clauses. So there’s actually a much better chance of the Voice being voted out of the Constitution once it is in there than there is of it getting voted in in the first place!

10. ‘There are better ways forward’

Maybe. But the No case only mentions one of them:

“Recognising Indigenous Australians in the Constitution … can be achieved without tying it to a risky, unknown and permanent Voice … but the Government has not given you this choice.”

This (unelaborated on but allegedly better) choice is presumably simply to recognise the Indigenous people symbolically somewhere in the Constitution and then to legislate for a Voice without it being mentioned in the Constitution at all. But the No case is not clear where in the Constitution this recognition would occur and what the wording would be. Dare I say we need more detail!

Neither does the No case offer any argument as to why this way forward would be better. All it does is suggest there might be a large number of voters who would support it. Even if this were true, it only shows that this way forward is popular, not that it is better. A reason it is not a better way forward is stated above under the third reason.

This reason also contains another of the No case’s spurious and untrue claims:

“When previous changes to the Constitution have been proposed, there has been a Constitutional Convention to properly consider options and details. … No such process happened here.”

In actual fact, during the twentieth century, of the 44 referendums on proposed changes to the Constitution that were put before the voters, only four of them were preceded by constitutional conventions. And all four of them subsequently failed at the poll.

There has been only one constitutional convention in the twenty-first century, at Yulara in the Northern Territory in 2017, and that constitutional convention produced the Uluru Statement from the Heart, the recommendation of which has yet to be put to a referendum.

So not only is the No case wrong about referendums in the past, it is also wrong about this one.

The No case concludes with a slogan (printed in bold type): “If you don’t know, vote no”. This also features prominently on page one. This statement betrays a lamentable lack of confidence in the strength of the case they have just presented. If they assume someone might get to the seventh and final page of their ‘Ten Reasons to Vote No’ and still not know how to vote, they must be only too painfully aware of the flimsiness of their arguments.

Furthermore, this slogan is not rational. If you don’t know what it’s all about, then the rational thing to do is to abstain or to vote informal. If you vote No, you are, in fact, expressing a firm opinion about something that you claim not to know about. In effect, you are saying you do know, and you know it’s a bad thing.

If you really don’t know whether the Voice is a good thing or a bad thing, you should vote appropriately, not by ignorantly and arbitrarily choosing sides but by voting informal.

The truth is that the Voice is a modest proposal which begins to give justice to the original inhabitants of our continent by enabling them to have a proportional impact within the existing structures of our government. There is something noble about that endeavor.

We need to ignore all the scaremongering lies that are being promulgated about it, and cheerfully vote Yes in the secure knowledge that we are on the right side of justice and on the right side of history.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

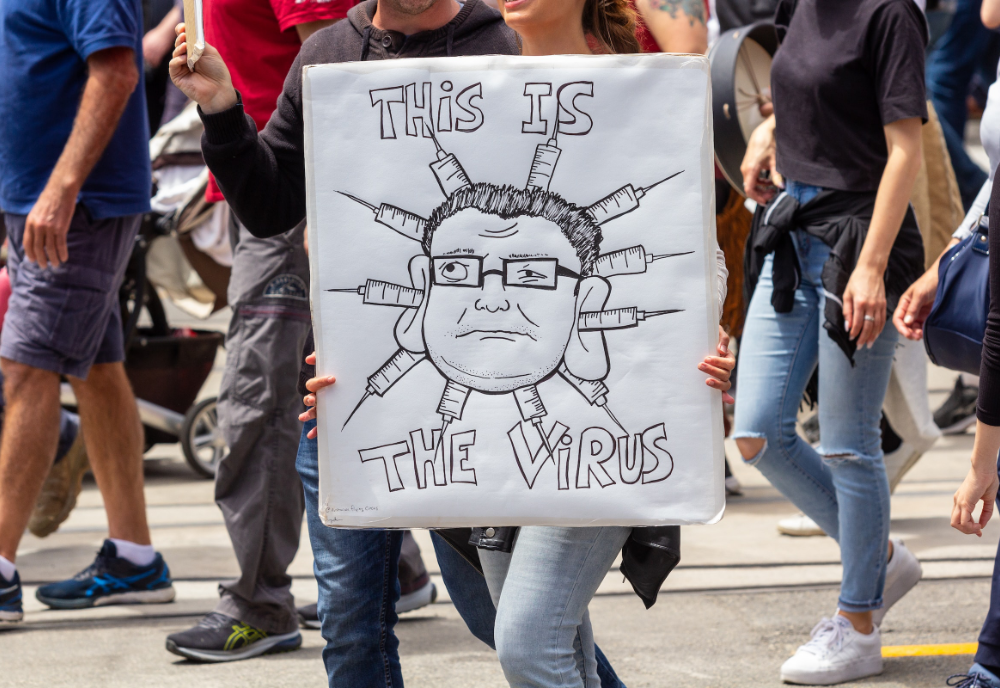

Photo by New Matilda on Flickr (CC)