The economy keeps making headlines for all the wrong reasons — stories about rising prices, supply shortages and a looming recession have been frequently making the front page these days.

The current economic crisis is deepening the long-standing issue of social inequality, widening the gap between the rich and poor — a problem that was already accelerated by the Great Recession of 2008 and the economic shock brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The richest country in the world, the United States, is among the most drastic examples of this trend. Today, American CEOs earn 940 per cent more than their counterparts did in 1978. A typical worker, on the other hand, only goes home with 12 per cent more money than workers from 1978 did.

As a report by the Economic Policy Institute demonstrates, rising CEO pay does not reflect a change in the value of skills — it represents a shift in power. Over decades, American politics has undermined the bargaining power of workers by discouraging and obstructing self-organising efforts, such as unionisation.

The growing wealth of a minority at the expense of the majority means power is concentrated in the hands of a few people, mostly men. It’s not surprising that figures such as Donald Trump, Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk have a disproportional impact on our communities — sometimes with devastating consequences that threaten our democratic institutions.

It’s more necessary than ever before to re-examine the fundamentals of our economic order. The search for alternative economic models, however, is made difficult by conventional thinking patterns.

Many believe we are facing a stark choice between a capitalist market economy on the one hand and a socialist-planned economy on the other.

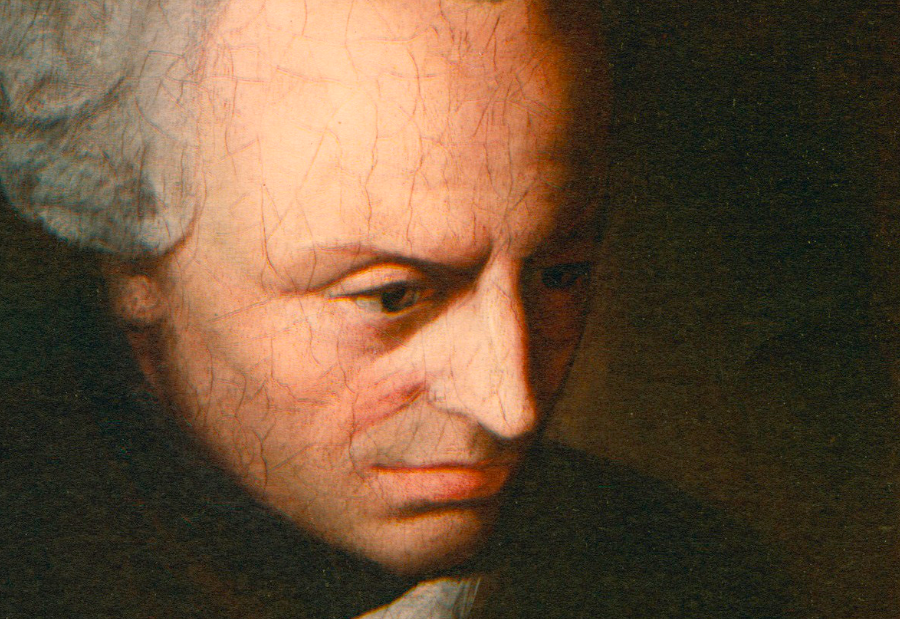

Although we live in a world that defines economic models in absolutist terms, it doesn’t have to be this way. We argue that the psychological and social perspectives on economy that were developed by 19th-century philosophers such as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, John Stuart Mill and Georg Simmel can help us re-imagine economics with a human face.

These thinkers were convinced that a good economic order had to incorporate elements of classic capitalism (such as a free market in goods and services) with elements of classic socialism (such as collective ownership of the means of production). This is what we call economic pluralism.

Hegel is a good example of an economic pluralist thinker. In his 1820 Philosophy of Right, he presented an extensive reflection on the modern economy. He discussed the market and its operating principles, social inequality and even the formation of desires through advertisements and consumer culture.

It’s more necessary than ever before to re-examine the fundamentals of our economic order.

Among the many topics he examined was the problem of affluence. Hegel was not just worried about the poverty created by the modern market economy, but also about the concentration of extreme wealth in few hands.

Writing hundreds of years before modern multi-billionaires arrived on the scene, Hegel already argued that “both of these sides, poverty and affluence, represent the scourge (Verderben) of Civil Society.”

Hegel’s analysis is even more prescient: He believed affluence created the counter-intuitive tendency among the affluent to feel victimised and disenfranchised by society. As a result, the affluent perceived all social demands, like taxes, as unjustified incursions into their personal freedom.

Hegel thought this sense of victimisation could lead to an unexpected bond between those at the very top of the economic pyramid and those at the bottom — a bond that overcame differences in lifestyle and mutual antipathy to form an alliance that attacks civil society from both sides. The phenomenon of Trump’s MAGA alliance is an interesting modern example of this.

Unlike some later socialists, Hegel did not think problems of affluence were best rectified by introducing a planned economy that enforces wealth equality. Instead, his approach was pluralistic.

He made a case for a free market exchange paired with co-operative modes of production, which are — in some respects — similar to modern-day worker co-operatives.

If most economic production in society was organised co-operatively, Hegel believed, wealthier subjects would be embedded in economic decision-making with others, replacing the detrimental “bond of victimisation” between the rich and poor with a collective identity based on shared economic agency.

When reimagining our current economic order, we can take a page out of Hegel’s handbook by focusing on worker co-operatives: economic ventures that are co-owned by workers that make productive decisions together, often — albeit not always — in a democratic manner.

Under what conditions are such co-operative modes of production successful? How can the state incentivise these forms of production within the existing market economy? And are these worker co-operatives really a way to achieve economic justice? These are the questions that, inspired by the past, might help us imagine a new, pluralist, more equal and human-centric economic future.

This article was co-authored by Johannes Steizinger, Associate Professor of Philosophy at McMaster University, and Thimo Heisenberg, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, at Bryn Mawr College.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Photo by David Suarez on Unsplash