This article is the third in a series on religion in the Australian Defence Force. Read the first article here. Read the second article here.

In 2012, the then Chief of the Australian Defence Force David Hurley – and now Governor-General – joined with fellow Christians at a ‘Spiritual Boot Camp’, hosted by the group Military Christian Fellowship (MCF). In addressing the group as the guest speaker, he admitted that he had to be careful about being seen to be involved in religious activities.

“I actually get complaints about having this meeting here today – ‘Why are you supporting religious activity in the ADF on ADF property as the CDF?’ Well, my response to that is: ‘Bring on the argument. But I’m the commander of the ADF for all of the ADF, not just bits and pieces people would like me to command’. So there are aspects that I need to be, frankly, a bit delicate about the way that I do business, but not ignoring the needs of my people in the organisation,” he said.

Hurley spoke about the challenges facing the Defence Force at that time, including deaths of soldiers in Afghanistan and cultural issues reported in the media. To his audience – fellow Christians – he emphasised the importance of the spiritual dimension to their work.

“If I was an American, I would say that our job is to ‘win and fight the nation’s wars’. That’s what we’re paid to do. And, in a spiritual sense, that’s what we’re asked to do, that’s what we’re told to do, that’s the duty we’re held to. We are here to fight the Lord’s wars in this world,” he told them.

Hurley was no ordinary guest speaker at the MCF event. He was the group’s Patron, having been appointed to that role in 2008 when he was Vice Chief of the Defence Force. During his seven years as Patron – before retiring as Chief of the Defence Force – he was an active participant in the MCF’s activities, including as guest speaker at Christmas events and at a number of seminars. According to the group’s regular magazine, Crossfire, Hurley not only provided advice for the MCF but also advocated for it to other members of Defence’s senior leadership. MCF members prayed that Hurley would champion the group “to the highest levels of Defence”.

The MCF is no ordinary group. It focuses on evangelising in the Defence Force. According to its current website, the MCF “exists to promote Christian faith in the Australian Defence Force (ADF)”, and the group’s passion “is to reach the Australian Defence Force for Christ.” It pursues this mission “primarily through supporting Christians who work in and around the ADF, helping the vital ministry of ADF Chaplains and reaching out to those that want to know more about Christ and the meaning of Christianity.”

The MCF website provides a range of tools for helping members introduce Christianity in the workplace. A 16-week course advises members on how to talk about Christ with others in Defence. It even teaches them how to treat people of other faiths, with an overview of the course noting: “The Bible teaches zero tolerance of other faiths. The ADF required total acceptance of other faiths. How do we reconcile the two? This study compares the ADF policy on religious freedom and compares it to God’s expectation of us.”

The MCF’s training materials, in encouraging members to talk about their faith in the workplace, describe the Defence Force as a “God-needy environment”. Deployment scenarios, in particular, appear to be ripe for the harvesting. “If we believe that God is in control of our lives then we must believe that God puts non-Christians in our lives for us to witness to, either directed [sic] or indirectly… He has put us here on purpose and expects us to make a difference.”

As Patron, Hurley regularly joined other senior Defence leaders at MCF events. Among guest speakers were figures from the Australian Christian Lobby (ACL). MCF pitched one such event, the ‘Battlesmart Seminar’ in 2010, as something that would encourage and equip Christians in Defence “to prepare for and succeed in spiritual battles”. Attendees were told they could expect to gain “Biblical perspectives and practical ways of ‘taking up the armour of God’ in the workplace.” Hurley opened the event; head of the ACL, retired Brigadier and former Chair and Patron of the MCF, Jim Wallace, also gave a speech.

High-level support for such activities is perhaps not surprising given the dominance of Christianity in Defence as an institution – including in its rituals, commemorations, formative training programs, such as ‘character development’, and the provision of pastoral care and wellbeing support. But it is also unsurprising when one considers the unusually high degree of religious affiliation – far above that shown by the national Census – among the Defence Force’s most senior leaders.

As outlined by former Army Colonel and Defence statistician Phillip Hoglin, a major gap exists between senior personnel and new recruits when it comes to religious affiliation, with Defence workforce data showing that about 85 per cent of leaders of one-star rank and above are religious – all of them Christian – but an overwhelming majority of personnel in the junior ranks are not religious. Only about 20 per cent of new recruits affiliate with a religion.

Some voices say the high level of religious affiliation of the top ranks is preventing much-needed secular reform, especially to the religious-based pastoral care and wellbeing capability, leading to worsening mental health outcomes for personnel. Hoglin blames the heavy identification with Christianity in the top ranks for making the reform of the chaplaincy capability “so difficult”.

Collin Acton, the former Director-General of Chaplaincy for the Navy, told ABC radio program Conversations earlier this year that those in the senior ranks had failed to question Defence’s reliance on “ordained ministers of religion” for supporting personnel. “They probably have good memories of when they were young men and they went out bush and the chaplain was there, or they went to sea and the chaplain was there, and they were a good chap. But it’s a different world now,” he said.

Traditionally, a significant part of the chaplaincy role has been to act as a confidant to commanders and other leaders, with chaplains assisting them, as Major General Chris Field wrote in 2018, in making ethical and moral decisions. According to the MCF, chaplains in Defence are a “key component the Lord uses to minister to people”. The group praised Hurley as a “strong support” for chaplains during his command roles.

Brigadier Ian Langford, a former commander of the special forces in Afghanistan who was “voluntarily” discharged this year, wrote in 2019 that he would “insist on having my unit Padre present in orders as well as make a genuine effort to gain his perspective before giving final direction and guidance prior to execution.” This practice, he said, had nothing to do with his competence as a decision maker but served his own need to “bring a lens of spiritual truth to what I was asking my Task Group to do.”

Defence leaders and chaplains talk about the spiritual side of service personnel, and Defence’s role in helping to foster this, as an important part of the fighting capability. In a keynote speech to a prayer breakfast in 2012, Hurley revealed that on his first day as the Chief of Defence Force he asked all the service chiefs to attend a church service. The idea was to “make a point on day 1” that there was another aspect that Defence and its leaders needed to address. In finishing the speech, he propounded the importance of “good solid Christian leadership” in helping to drive the country forward.

… Hurley revealed that on his first day as the Chief of Defence Force, he asked all the service chiefs to attend a church service.

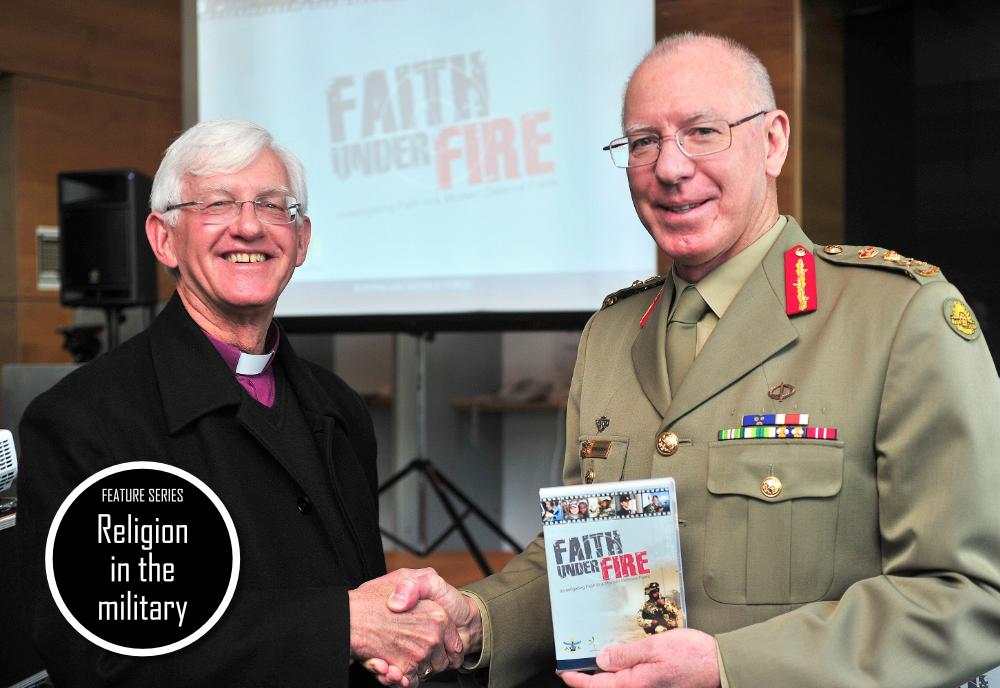

Hurley’s desire to foster this spiritual element was a motivating drive behind his introduction of a training program that aimed at promoting Christianity within Defence. In 2011, he launched the DVD-based ‘Faith Under Fire’ program at an MCF event. He also appeared in a recorded introductory message at the beginning of the DVD series and in a promotional video. The resource was based on a program about Jesus that had been developed by the Centre for Public Christianity.

According to a source, development of ‘Faith Under Fire’ cost taxpayers about $70,000 and was a dogmatic attempt to address the cognitive dissonance that exists between what’s written in the Bible, killing other people, and the notion of ‘just wars’. According to the then Anglican Bishop to the Defence Force in 2012, Len Eacott, ‘Faith Under Fire’ was pitched to commanding officers as “being highly relevant to human capability development”. It is understood that some Defence chaplains have faced pushback from new recruits for using the resource as part of ‘character development’ training.

At the MCF’s Spiritual Boot Camp in 2012, Hurley made it clear that he viewed ‘Faith Under Fire’ as having a role to play as part of the wide-ranging cultural reforms taking place within the Defence Force, following the media storm over scandals about behavioural issues in the institution. He told the gathering that Defence Force needed ‘Faith Under Fire’ and that he wanted to “broaden” it by enmeshing, but not enforcing, it in Defence.

Given the cultural stranglehold that Christianity has over the Defence Force, it is unsurprising that disturbing attitudes towards non-religious personnel and missionary tendencies seemingly go unchecked. The view that non-religious service personnel are somehow inferior, ill-equipped or in need of God, can be found among the taxpayer-funded Religious Advisory Committee to the Services (RACS) accused of blocking secular reforms in Defence and also among Defence chaplains. But former Defence chiefs have also espoused such views.

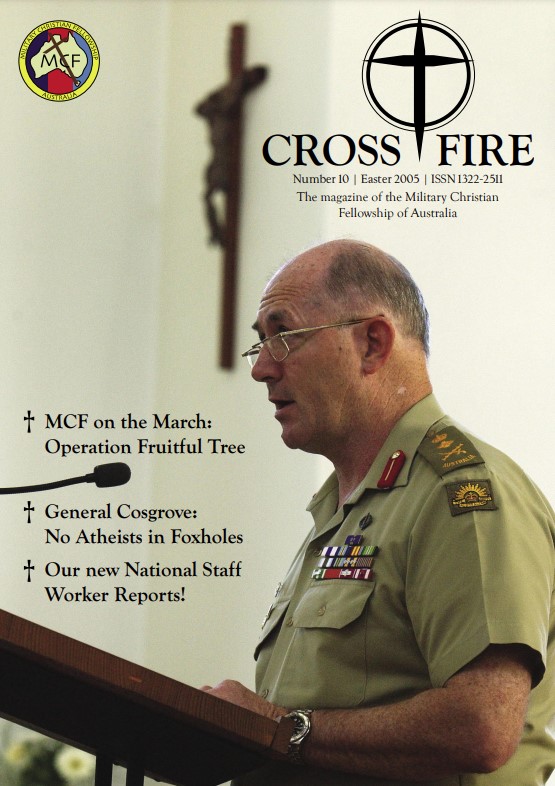

In 2004, the then Chief of the Defence Force General Peter Cosgrove, in a speech to the National Day of Prayer Breakfast, reportedly told the audience that the “old saying” that there were “no atheists in foxholes” was as true as ever. “At times when the question of their own mortality is writ large in their minds, their thoughts will turn to that axiom of faith for us all, the conviction that there is a higher direction, purpose and safeguard to our existence. I have had nearly 40 years of service and I know that this still holds as true today as ever it did in earlier times,” he said.

General Peter Cosgrove on the cover of the MCF’s ‘Crossfire’ magazine in 2005.

Another former military man – and, indeed, another former Governor General – Michael Jeffery appeared in a promotional video, published in 2012, touting the importance of the ‘Faith Under Fire’ program for Defence personnel. In the video, he said that soldiers without a practising faith would have “no basis on which to communicate” with locals when arriving in villages and meeting with tribal leaders.

As members of Defence promoted ‘Faith Under Under’ in a public arena, the old trope – of there being “no atheists in foxholes” – was never too far away. Major David Doust told ABC radio that the sentiment was “clear” that there was truth to the saying. Bishop Eacott wrote that a special forces officer had told him soldiers go from “general indifference regarding God, to wanting a chaplain at hand to talk with.” Then Army Reserve Chaplain – and now the chair of RACS – Grant Dibden told Christian media in 2012: “… it’s pretty true, the old statement that there’s not many atheists in the army. We’ve been an army at war. You see poverty, and are faced with the possibility of your own death – these guys have to think more deeply.”

While such attitudes play well in some religious circles, they are surely insulting to the non-religious men and women who have served – and died – for Australia in foxholes across the world. As historian and writer Chrys Stevenson has argued, the ANZAC ethos was borne out of mateship, irreverence and contempt for authority – including religious authority. “Primarily, it was their faith in each other, not in God, that sustained the ANZACs and, as their legend emerged as the defining moment in the young nation’s history, mateship was elevated to almost-religious status in the national psyche,” she wrote.

Being perceived as a ‘Christian military’ is surely at odds with the expectations of Australian taxpayers and even most personnel in the now majority non-religious workforce. According to Hoglin, it is also dangerous, giving rise to an “operational bias” that may provide an adversary with “another point of difference and a theological reason to maintain a conflict or target ADF personnel” when operating among non-Christian populations.

In Afghanistan, there was a narrative that Australian soldiers were part of a “crusading” force. Alarmingly, a number of Australian soldiers added Crusaders’ crosses to their uniforms while fighting the Taliban. The Australia Defence Association blamed “poor cultural standards” in Defence, with the association’s Neil James labelling the display of the symbols as “wrong morally” and as “exceptionally dumb … in a counter-insurgency war”. While Defence said it did “not condone or permit the use” of the Christian iconography, how could people in leadership not have known?

To help counter the narrative, one chaplain, John Saunders, handed out Qur’ans as gifts for Mullahs. As reported in the Australian Army Chaplaincy Journal, the tactic had the effect of sending the “all-important subliminal message that the Australian military presence was not that of ‘Crusaders’”. As Chaplain Martin Johnson noted in the same journal edition, chaplains had to work to combat the notion that religion was a source of conflict in the world and to “contradict the insurgents’ narrative that we are on crusade.”

Yet, to this day, the staff of a formal branch of the Army – the chaplaincy branch – continue to wear on their uniform an official badge with the motto “In this sign conquer”, inlaid over a Maltese Cross. Despite calls from minority faith groups for this to be removed due to the motto’s association with the Crusades, the Defence Force has so far failed to act.

Having endured its fair share of well-publicised cultural problems, the Defence Force has successfully undertaken reform efforts in recent years. These have included efforts to modernise its culture and promote the inclusion of women and of groups such as minority faiths and people of the LGBTIQ community.

Clearly, however, it is still to recognise the need of reforming what is perceived as an overly Christian institution into a secular one. It also needs to respect and celebrate the contribution of non-religious personnel, and provide appropriate secular pastoral care and wellbeing support to meet their needs.

If the Defence Force wants to become culturally diverse, facilitate inclusion and have the broadest possible relevance to society, the transition towards secularism is “essential, if not overdue”, argues Hoglin. Given the religious affiliation of those in the top ranks, it seems unlikely the ignition required to spark that effort will come from within Defence any time soon. It will have to come from external pressure – from Australians who believe having a secular military is something worth fighting for.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Department of Defence (Commonwealth of Australia).

*This article has been revised on 30 November 2023.