This article is the first in a series on religion in the Australian Defence Force.

Every three months, Australian taxpayers pay to send a group of religious clerics, including bishops, senior pastors, a rabbi, an imam and other religious figures, to Canberra to meet at a modern hotel next to the capital’s airport. At 8.30 in the morning, they meet over consecutive days to discuss matters relating to religion in the Australian Defence Force (ADF).

Few Australians – even members of the Defence Force – would have heard of the Religious Advisory Committee to the Services (RACS). Many, no doubt, would be surprised to learn of the privileged place this committee holds in Defence and the influence it wields.

Recent allegations calling into question the behaviour of RACS, centering on claims that it has stifled needed reforms and forced out of the Navy a former top chaplain who was pushing for such reforms, raise serious questions about the appropriateness of the committee’s place in the modern ADF.

Rationale can reveal that new information, obtained from the Department of Defence under Freedom of Information (FoI) laws, adds further weight to the claim that the committee is an anachronism that no longer serves a useful purpose in the modern Defence Force.

According to its Memorandum of Arrangement with the Commonwealth, RACS is responsible for providing “religious support, including advice, to Defence so as to ensure that the religious, spiritual and pastoral needs of ADF members are appropriately maintained”. The committee’s key objectives include: providing a direct link between chaplains, Defence and respective civilian religious institutions; upholding the freedom of all faith groups within Defence; nominating people for the roles of chaplain and principal chaplain; and providing advice and assistance to chaplains and Defence personnel in relation to worship, religious education and pastoral ministry.

Since it was established as a statutory body in 1981, RACS has enjoyed a direct line to the Minister for Defence and to the Chief of the Defence Force. The 10 members of the committee are nominated by their respective religious institutions for five-year terms. They are each accorded two-star status – equivalent to that of general.

While the committee’s ongoing presence appears more like an artefact from a bygone era, it is, perhaps, emblematic of an institution which remains, according to former Army Colonel Phillip Hoglin, “overtly Christian” and “functionally, if not structurally, non-secular”.

Australia as a whole is rapidly becoming less religious, and the same trend is happening in the military – but even more so. Official Defence figures show that, as of 2019, almost 56 per cent of full-time Defence members are not affiliated with a religion – up from 31 per cent in 2003. With that rate rising at 1.5 to 2.5 per cent a year, the 2022 figure is likely to be around 60 per cent. Notably, among new recruits about 80 per cent report that they have no religion.

Yet religion – and, mostly, Christianity – retains a privileged place in the Defence Force, dominating rituals, commemorations and even the instruction and delivery of ‘character development’ during formative training for new service personnel.

Defence uses a religious framework in the provision of pastoral care and wellbeing support, with 160 full-time and 150 part-time clergy embedded in ships and in military units to provide frontline support for personnel. But calls are mounting for the ADF to move away from its reliance on religious-based chaplaincy.

At Senate Estimates last week, Senator David Shoebridge asked the top brass whether they could “see the problem” of Defence relying on Christian-based chaplaincy to support its people.

In 2020, the Navy did see the problem. It identified the need to introduce non-religious wellbeing support into its chaplaincy branch after damning testimony to a Defence Force Remuneration Tribunal revealed that religious-based chaplaincy put up numerous barriers to Navy personnel getting appropriate support.

Despite the recognised need in Navy for, and subsequent introduction of, secular wellbeing officer roles, known as Maritime Spiritual Wellbeing Officers, the other services, Army and Air Force, have so far failed to take similar action.

Leading the reform effort at the helm of Navy’s chaplaincy branch was Collin Acton OAM, who, during his more than 30 years in the Defence Force, changed his worldview from that of a religious person – Christian – to that of a humanist. After retiring as Director-General of Chaplaincy in 2021, Acton remained in Navy while continuing to advocate publicly for the Defence Force as a whole to reform its pastoral care and wellbeing support model.

In numerous public comments, Acton has called for the Defence Force to move away from its reliance on religious-based chaplaincy to a model that recognises and responds to the increasingly non-religious make-up of serving personnel. For that, he drew the ire of the clerics.

FoI documents show that RACS used its privileged access to the top echelons of Defence in the middle of 2022 when it wrote to the Chief of the Defence Force to raise its ‘concerns’ about a radio interview on the ABC program Conversations featuring Acton and published on Anzac Day this year. In that interview, Acton shared his personal story of a career serving in the Navy and repeated his calls for reform of the chaplaincy model in Defence.

RACS’ subsequent letter to the Chief of the Defence sparked an investigation into Acton, who was later called to a meeting with senior personnel at Navy Headquarters. At that meeting, the message was clear that he would have to leave the Navy if he wanted to continue advocating for reform. Acton chose to continue his advocacy.

Speaking to The Secular Agenda podcast in early October, days after his resignation took effect, Acton said he was in “no doubt” there was a desire at the top levels of Defence for the issue to just go away. “And my resignation was one way of achieving that. But, yeah, RACS was right behind this, and it was placating RACS’ desire to get rid of me that led to it,” he said.

For Acton, the response from RACS to his public advocacy was disappointing but not surprising. Fresh in his memory was the experience of having to fight RACS’ efforts to ‘stifle’ his reform agenda when he served as Director-General of Chaplaincy in Navy and had to deal with RACS on a regular basis.

Given its deep involvement in recruiting chaplains and overseeing chaplaincy branches in the Navy, Army and Air Force, RACS has a self-interest in Defence maintaining a religious-based model of pastoral care and wellbeing support. But, as Hoglin notes, RACS cannot claim to even represent the fastest-growing of Defence’s ‘religious’ groups – atheists and agnostics. With the collapse of religious affiliation among service personnel, RACS is increasingly irrelevant to the needs of serving men and women.

RACS is, effectively, a taxpayer-funded lobby within Defence, doing the bidding of religious interests. For non-religious personnel, however, there is no equivalent body to represent their views and needs to the top echelons of the Defence Force. Without such advocacy and support networks for non-religious personnel, there is a risk, Hoglin warns, that this “large and emerging demographic will be under-represented in relevant forums” and excluded from important debates.

The FoI documents of meeting minutes show RACS is acutely sensitive to public commentary about the changing religious demographics in Defence and about the need for secular reform of the pastoral care and wellbeing capability. In recent meetings, for example, RACS has discussed efforts to produce journal articles to respond to such commentary – in particular, to Hoglin’s article, ‘Losing Our Religion’, published in the Defence journal The Forge.

The privileging of religion leaves Defence vulnerable to not only shifting demographics but also shifting societal norms and values. As Australian norms and values have progressively moved to recognise and adjust to a more diverse and multicultural nation, the views of some religious communities – specifically, the most conservatives ones – have hardened and moved further to the margins. This is especially so on issues such as sexual ethics and sexuality, abortion rights, same-sex marriage, and voluntary assisted dying.

Over the past decade, the Defence Force has invested much effort in addressing cultural issues to help foster welcoming and inclusive work environments. Facing “significant challenges” to meet recruitment and retention targets, it has become imperative to appeal to broader sections of society, particularly women, minority groups and LGBTIQ people. Part of this effort includes Defence embedding respect for others and being inclusive among its core values and behaviours.

The FoI documents reveal an admission by RACS that the views of some chaplains may be at odds with publicly-stated Defence values. Minutes from a meeting in March this year detail how, in a discussion about the committee’s Accountability and Diversity statement, it was recognised that working in the “inclusive, diverse and multifaith space” of Defence “may not suit some admirable faith group leaders”. The meeting’s minutes state:

Consequently, we are committed to exploring conversations with potential Chaplains as part of the recruiting process as well as with serving Chaplains. The intent of these conversations is to promote positive attitudes and outcomes and to prevent inappropriate behaviour and/or reshape any disrespectful attitudes towards those who are ‘other’ than one’s self, such as people from other cultures, diversity groups, beliefs, religions and traditions.

In 2020, part of the evidence that informed Navy’s decision to introduce non-religious wellbeing officer roles to its chaplaincy branch was that some female personnel did not want to talk with clergymen – who were mostly old and male – about issues affecting them.

The FoI documents reveal ongoing disagreement between RACS and a women’s working group that was established to promote more female representation in chaplaincy. In December last year, the meeting minutes said that RACS had reviewed its progress on including women in chaplaincy and acknowledged the need to be “more proactive in challenging the culture and environment that does not further the healthy inclusion and place of female Chaplains in Defence.”

In March this year, the women’s working group expressed ‘disappointment’ with RACS for having supported only three of eight of the group’s recommendations. While the minutes note that RACS supports women in chaplaincy and proactively engages in the recruitment of women within chaplaincy, the committee agreed with the women’s working group that it would need to take “practical steps as to how RACS members may further incorporate inclusivity of women” and “address cultural issues militating against inclusivity.”

Decades ago, RACS put up barriers to female Defence personnel even being able to access a female chaplain. In 1991, a Jewish representative on RACS had to “break a deadlock” on the question of allowing Air Force to appoint its first female chaplain. In a 2017 article, Rabbi Dr Raymond Apple recalled that the five Christian members on RACS “were at odds about the proposal” because “some had a rooted objection to women clergy”.

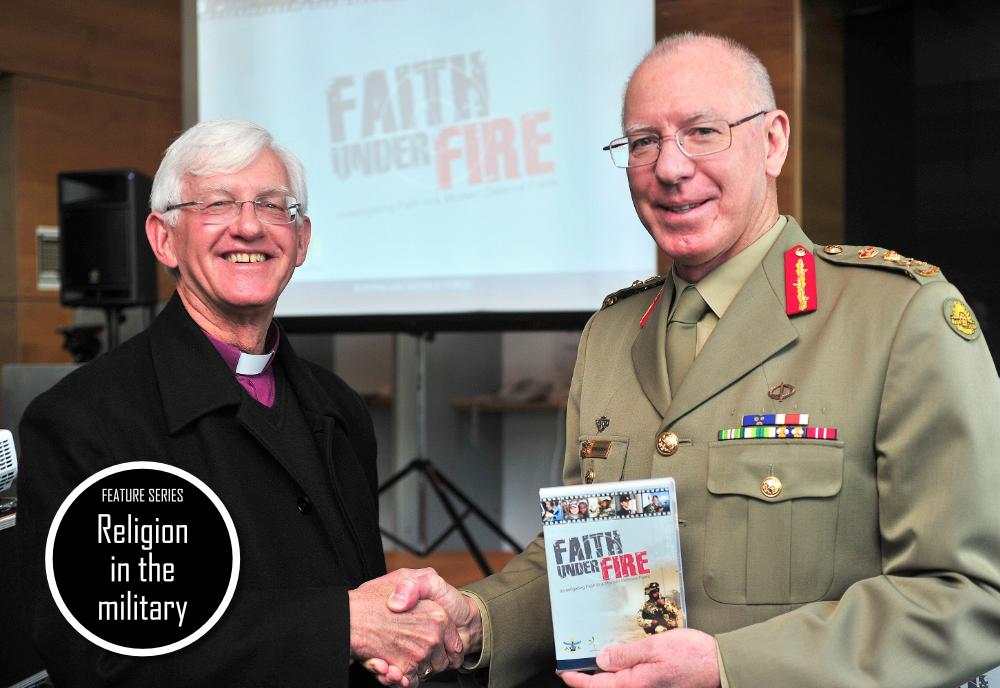

Recent public comments from the chair of RACS, Anglican Bishop Grant Dibden (pictured), also appear at odds with Defence’s values of respecting others and promoting inclusion – especially when it comes to the non-religious majority of the Defence workforce. Writing in the Christian publication Eternity News earlier this year, Bishop Dibden said it was “not right to leave the physical fighting to the non-Christian”. He claimed that “ … where there are more soldiers who follow the Lord Jesus, it is more likely that evil will be restrained in the heat of battle.”

In 2012, then as an Army Reserve Chaplain, Dibden echoed the old trope that there are ‘no atheists in foxholes’ when he told Eternity News: “I think it’s pretty true, the old statement that there’s not many atheists in the army. We’ve been an army at war. You see poverty, and are faced with the possibility of your own death – these guys have to think more deeply.”

Acton, speaking at a webinar earlier this year, revealed that such attitudes towards non-religious Defence personnel continue to be used to bolster the case for having chaplains embedded alongside Defence personnel. Speaking about the ‘no atheists in foxholes’ trope, Acton said there were a couple of problems with this view:

Firstly, it’s not true. There are atheists … and religiously disinterested people in foxholes all around the world. And there’s not one shred of evidence to support the view that combat commonly causes people to turn to God. If it were true, one would expect to see a spike in religious adherence from those who have been deployed on active service. And over the last 20 years in Australia we certainly have had a large number of Australians who have been deployed on active service, and there has been no spike, because it isn’t true. The view also fails to take into account the large number of humans who go through other kinds of adversity without the need to resort to religious faith. I think it’s disrespectful to their stories of coping without religion.

RACS also appears to be operating outside its purpose and responsibilities, as stated in the Memorandum of Arrangement with the Commonwealth, by encouraging proselytising in the Defence Force. In the Anglican News magazine shortly after his appointment to RACS in 2020, Bishop Dibden said: “I want to encourage the chaplains to make disciples who make other disciples.”

In a speech to Anglicans to mark Defence Sunday last year, he said chaplains are “missionaries in the Defence Force”, caring for the ‘soul’ of the institution. He added:

Our heart is to minister in the Australian Defence Force, be ambassadors for Christ, and to represent the Anglican Church in the complex secular context that is Defence… Any time we do anything in Jesus’ name, we are participating in the mission of Christ and pointing people to God. We’re missionaries in the Defence Force …

Surely it is not the Defence Force’s job to be ‘pointing people to God’.

There are signs that RACS is increasingly concerned about its ability to continue influencing the Defence Force into the future. FoI documents of meeting minutes reveal a preoccupation with the question of the committee’s focus for the future. In December last year, the committee discussed what RACS needed to do to be “more proactive and provide inspiration and moral direction” to Defence. It identified the need for RACS members to engage more with senior Defence officers and other Defence committees to “increase their profile and influence”.

Yet the future of RACS, with its increasingly irrelevant religious clerics lording it over an institution marked by decreasing numbers of religious adherents, appears assured without external intervention from the federal government. Within Defence, it is claimed, there is an unwillingness to start a ‘religious war’ with RACS.

For now, at least, RACS will continue to exert undue and unwelcome influence over the Defence Force’s primary model of pastoral care and wellbeing support – religious-based chaplaincy. The next article in this series will take a deeper look at whether religious-based chaplaincy is fit for purpose for a modern Defence Force.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Department of Defence (Commonwealth of Australia).