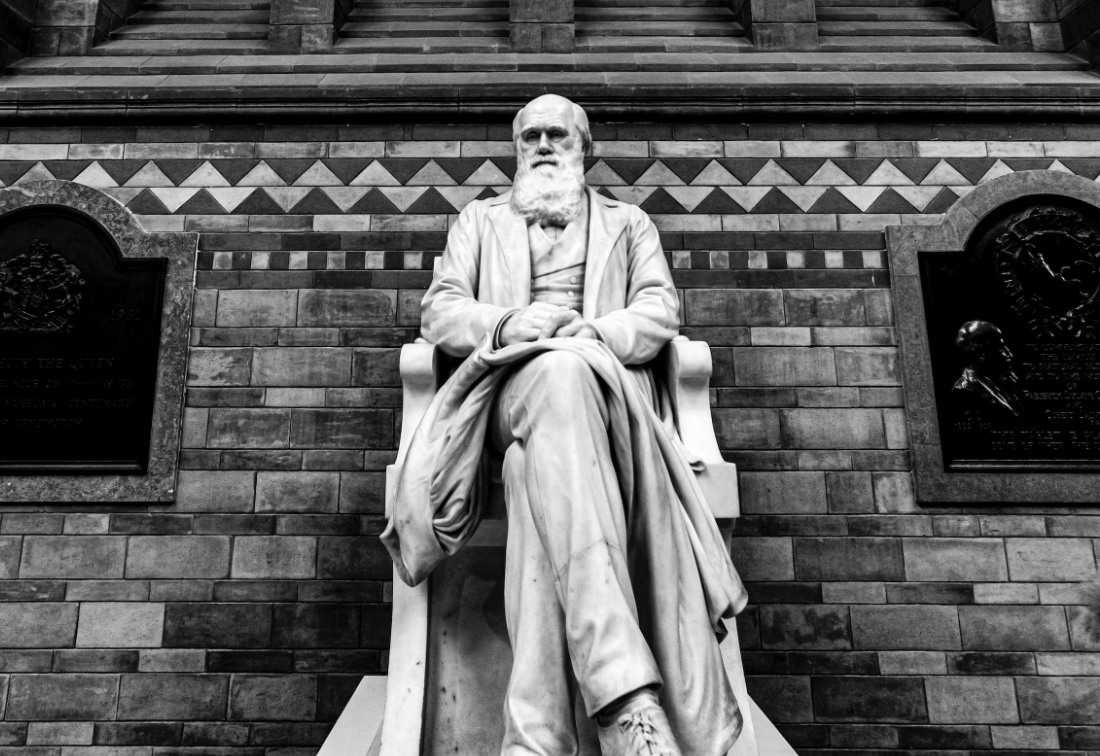

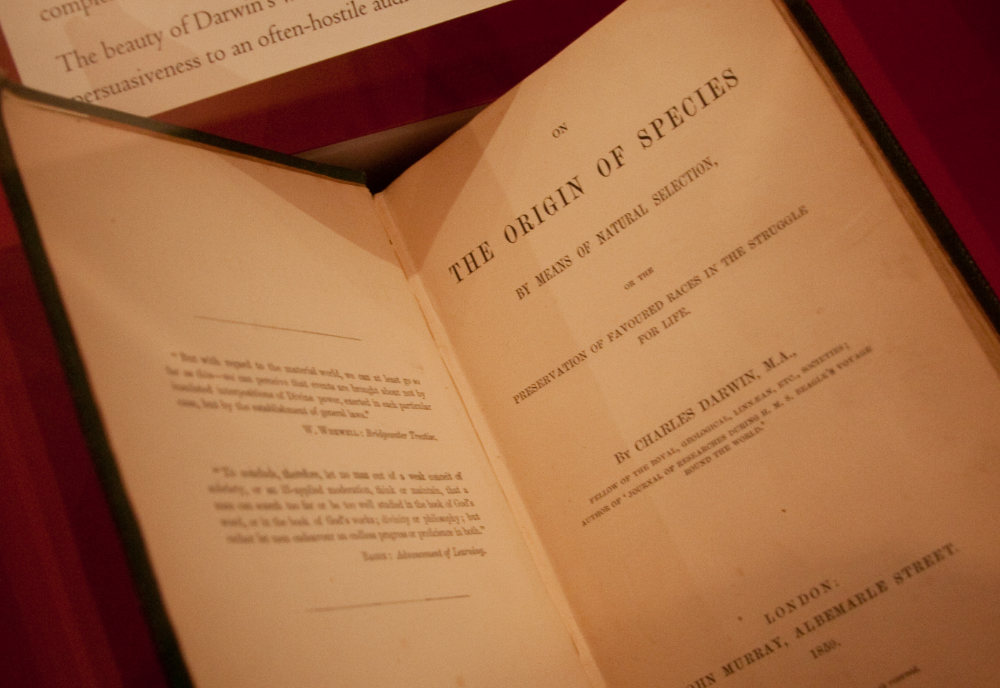

For most of the first 15 years of the 21st century, there was a fierce debate between rationalist supporters of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and advocates of creationism, a religiously-inspired view that evolution could not be explained by random variation.

The zoologist and atheist Richard Dawkins was perhaps the most high profile protagonist in the rationalist camp, but there were many more. Philosopher Daniel Dennett and commentators Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens teamed up with Dawkins to decry what they saw as the anti-science positions of those critiquing Darwin.

There were prominent scientists with somewhat different views, such as paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who pointed to what he called ‘punctuated equilibrium’: the sudden appearance of new species that did not match Darwin’s ideas of gradual evolution. But for the most part it was a battle between the scientific community and the creationists.

All that has evaporated. Darwin, and the efficacy of his theory of evolution, no longer capture much public attention – from either side of the argument. It is worth reflecting on why, because this case carries some lessons about the use of scientific theories.

Life on Earth may not be the product of a grand design, but there is absolutely no doubt that life is increasingly being designed in the laboratory by scientists using the knowledge gleaned from evolutionary observation.

Dawkins wrote a book called The Blind Watchmaker, in which he argued that evolution was driven by blind, random forces. Once scientists began to get an understanding of evolution and genetics, however, they were no longer blind, they could manipulate the processes. There are now many ‘seeing watchmakers’ in laboratories finding ways to push evolution in new directions.

Life on Earth may not be the product of a grand design, but there is absolutely no doubt that life is increasingly being designed in the laboratory by scientists using the knowledge gleaned from evolutionary observation.

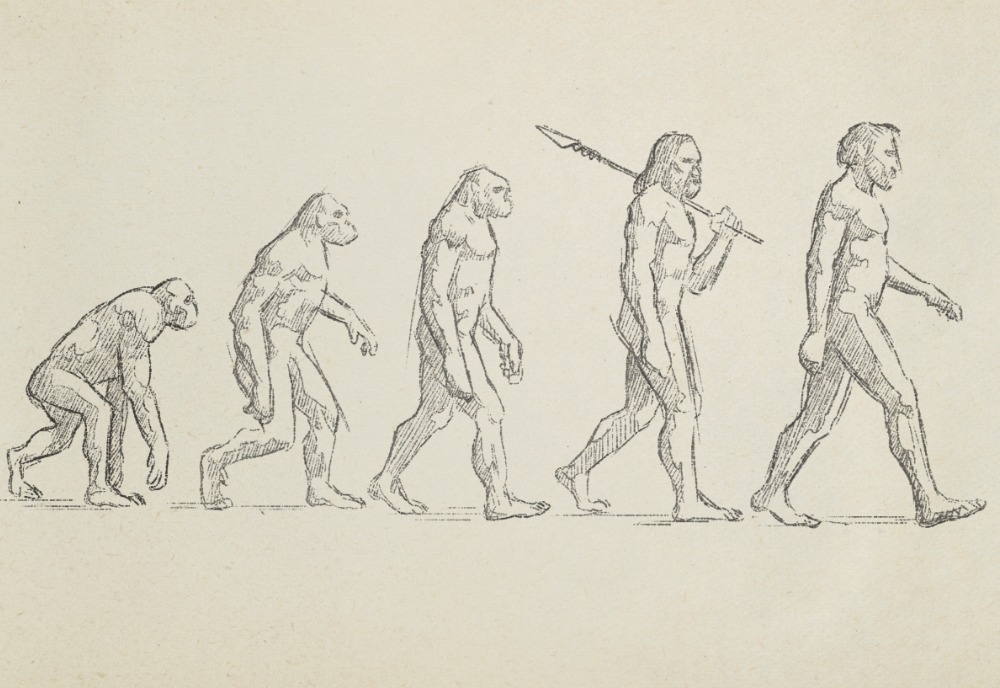

In one sense, that has been the case for thousands of years. Humans have bred animals in a way that has been anything but random. Breeding is artificial rather than natural selection, although there had to be considerable manipulation of natural processes for it to work. Consider, for example, how dogs have been reared since prehistoric times.

The manipulation of species, especially of humans, is, however, entering an extraordinary new level of intensity. So much so that there are some arguing for the end of Homo sapiens. Historian Yuval Harari, author of Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, contends that: “Homo sapiens as we know them will disappear in a century or so, not destroyed by killer robots or things like that, but changed and upgraded with biotechnology and artificial intelligence into something else, into something different.”

Harari is more at the extreme end of those arguing for the so-called ‘singularity’: a time when the technology humans have created takes over. But there is little doubt that humans, animals and plants will not be left to evolve randomly. Instead, they will be controlled very deliberately. It is what is often called the anthroposphere – an Earth partially created using artificial means. Natural processes will no longer dominate.

The impact of these technological developments is already occurring and will speed up. The Biden administration just passed the Executive Order on Advancing Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Innovation for a Sustainable, Safe, and Secure American Bioeconomy, which calls for a: “whole-of-government approach to advance biotechnology and biomanufacturing towards innovative solutions in health, climate change, energy, food security, agriculture, supply chain resilience, and national and economic security.” The aim is to change life on Earth, in other words.

“We need to develop genetic engineering technologies and techniques to be able to write circuitry for cells and predictably program biology in the same way in which we write software and program computers,” the Executive Order says.

It is not just biological changes in prospect. There is also a proposed merging of humans and machines. Forbes magazine, for example, published an article on how transhumanism will transform the future by 2030, including body augmentation and dramatically changed business practices. Financiers are talking about ‘Human 2.0’ – transhumanism as the next technological trend. “We’re on the brink of creating radically smarter, healthier and stronger versions of ourselves,” enthuses one asset manager.

All of this is about as far removed from Darwin’s idea of natural selection as it is possible to conceive. It carries some important lessons about the unavoidable limitations of science, which may also point to the responsibilities that scientists and others have in dealing with arguably the most important changes that have ever faced the human race.

A scientific theory cannot include the knowledge that scientists have of that theory. As soon as they act on that knowledge, what occurs is something that cannot be predicted.

Human knowledge always stands outside, looking on. So when trends such as transhumanism and biomanufacturing are presented as irresistible processes impossible to combat, that cannot be true. We are always looking on at what we are doing, and we can make choices about whether it is a good thing.

If this sounds obvious, it’s because it is. But just as few have noticed the fading of the debate over Darwin, so it is easy to miss that all humans inevitably observe scientific complexity and make decisions about how it will affect the future. It is something crucial to remember, as we face what will be perhaps the most momentous choices humans have ever faced.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Hulki Okan Tabak on Unsplash.