Many hold that growing inequality is one of the most serious problems we face. But there are others who hold that it does not matter. There are even those who hold that inequality is a good thing and that there ought to be more of it.

But at least two questions arise when we address the matter of ‘inequality’. The first question is: ‘Inequality of what?’ Economic inequality? Racial inequality? Gender inequality? The second is: If it is held that some, or all, of these forms of inequality matter, precisely why do they matter?

This article examines one particular form of inequality: inequality of ‘epistemic power’. We begin by explaining what is meant by this expression, and then argue for its importance.

One person has epistemic power over another if they can influence what the other believes. There are at least three dimensions to epistemic power. These are: 1) expertise; 2) the power of being heard; and 3) prestige.

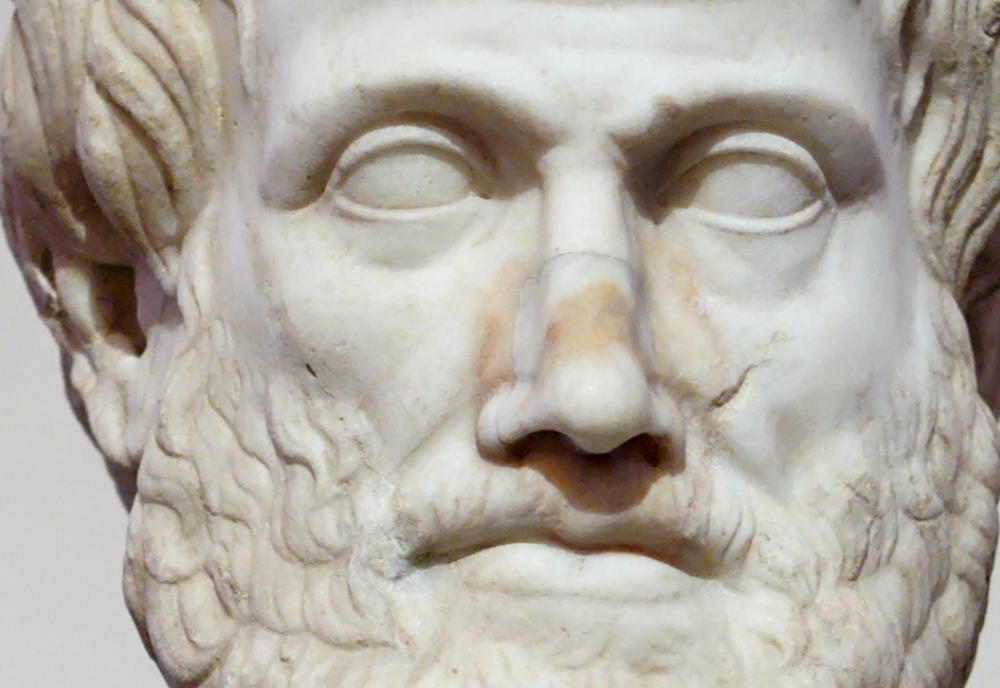

Let us begin with the expertise dimension. One of the most obvious ways in which one person can influence what another believes is by having greater knowledge or expertise. They will be better placed to marshal those facts and arguments that support their favoured position than will someone lacking in such expertise.

And here it is important to note the position the person with greater knowledge chooses to defend need not necessarily be the position that is true, nor even the position they themselves sincerely believe to be true. It might simply be the position that, for one reason or another, the person with the greater epistemic power wants the other to believe.

The second dimension of epistemic power is what we are calling the ‘power of being heard’. This refers to the power or ability of a person to be heard, or read, or in any way have their views known by a large number of people. Plainly, a prominent journalist, politician or celebrity will have their views heard by a much larger number of people than the average citizen. Such people will have a greater power of being heard than most.

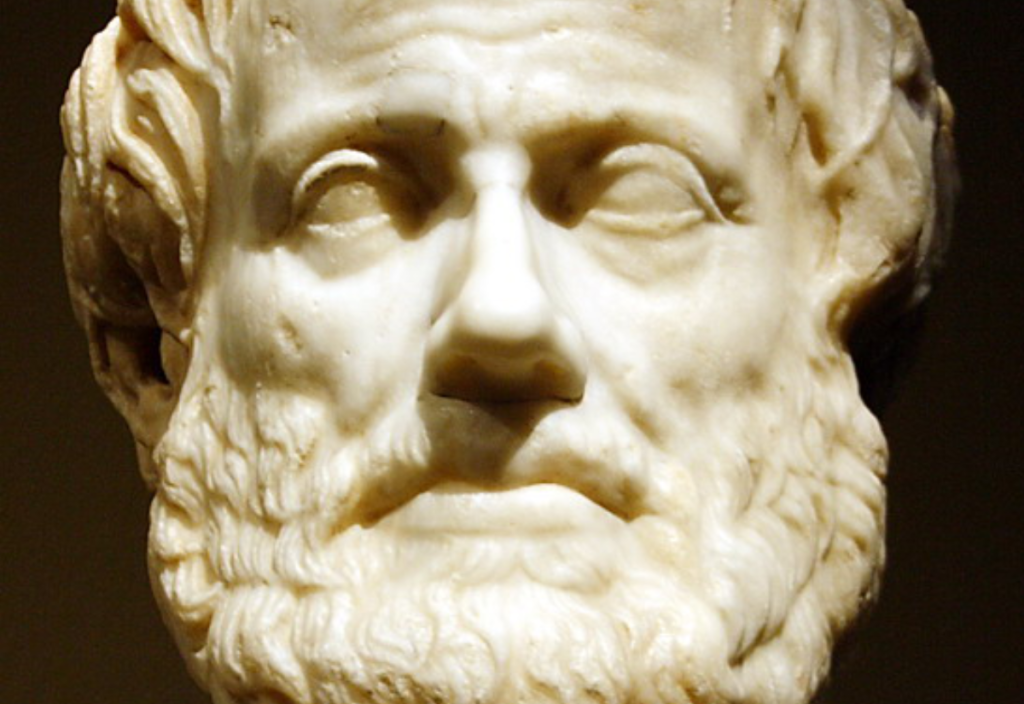

The third dimension is prestige. Sometimes, our inclination to accept a view that has been offered may be influenced by the perceived prestige of the speaker. We might be more inclined to accept what a person has to say if they have many letters after their name, or are affiliated with a prestigious institution.

It should be noted here that the prestige dimension is different from the expertise dimension. Someone has more of the expertise dimension of epistemic power if they really do have more knowledge than most. But a speaker has more of the prestige dimension if there is something about the speaker which – rightly or wrongly – convinces some listeners that the speaker knows what they are talking about.

So, having a lot of letters after the speaker’s name might persuade some that the speaker knows what they are talking about. But, for some listeners, simply having a confident demeanour might be a sign the speaker is to be believed. And, perhaps, for some listeners, the fact a speaker is famous, or rich, or from a certain background, or of a certain gender or ethnicity, might affect the extent to which the speaker could be seen to be authoritative. Many factors can enter into the prestige dimension of epistemic power.

In a variety of ways, inequality of epistemic power interferes with the ability of democracy to work in the ways we would like it to work.

Why is democracy thought to be desirable? Amongst the answers that have been given are the following: it provides a way in which rulers acquire legitimate authority to rule; it provides a means by which bad rulers can be removed without bloodshed; it is a means by which a society can come to adopt policies that are at least probably true; it provides a means by which a wide range of views can be brought to bear in deliberation, so that a form of ‘collective wisdom’ might be exercised in political decision making. If democracy is to deliver any of the goods promised above, there needs to be a sufficient level of equality in epistemic power.

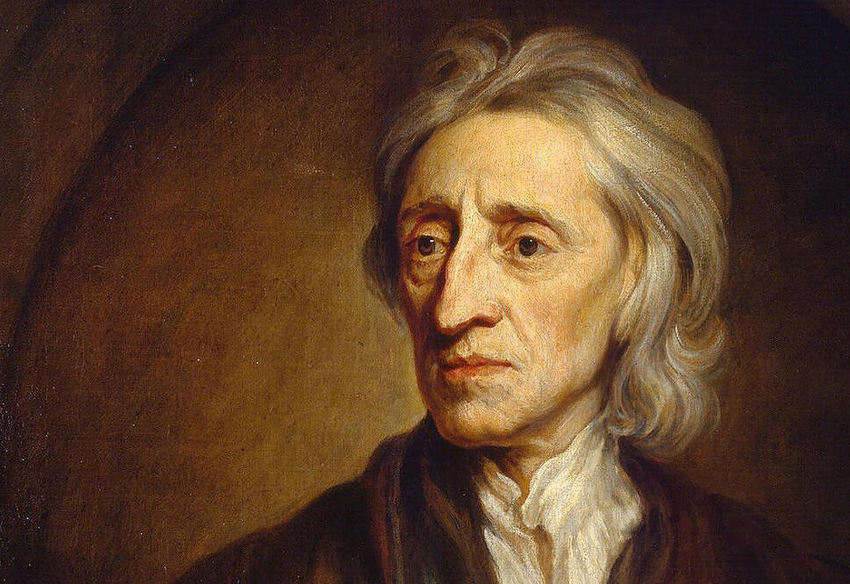

Let us begin by looking at the thesis that democracy is a means by which rulers come to have legitimate power. The key idea here is often attributed to the English philosopher John Locke. For Locke, elections are a means by which the population as a whole express their consent to be ruled over by a particular party. In choosing to vote for one particular party, people are, Locke suggests, in effect saying: “We consent to be ruled over by this party”.

In a variety of ways, inequality of epistemic power interferes with the ability of democracy to work in the ways we would like it to work.

Now, normally consent makes a huge moral difference to the acceptability or otherwise of an action. If a stranger were, without my consent, to stick a needle in my arm, it would be assault. But if a doctor were, with my consent, to do the same to inoculate me against some disease, it would be an entirely different matter. Consent can play a very important role in making something morally acceptable.

But there is a complication. Let us consider again the example of a doctor administering a hypodermic needle to a patient. The doctor assures the patient it will protect against the flu. But suppose it does no such thing. Suppose it is a mild poison that will make the patient ill. Moreover, we will assume the doctor is fully aware of what they have done.

Under these conditions, would we say the patient had consented to having the needle? I think we would only say they had consented in a conditional sense. They had consented on the assumption it would protect them from the flu. But, since this assumption was false, I think we feel reluctant to say they had consented in the full sense of the word.

Similar remarks can be made about a person voting for a party – let us refer to it as ‘Party A’ – in an election. Suppose Party A promises to stop the construction of a dam. Voter Smith votes for Party A on the understanding it will stop the dam. But then, when elected, Party A proceeds to build the dam. Had voter Smith consented to Party A getting into power? In one sense, they had, since they had voted for Party A. But, at the same time, I think we are inclined to say the degree to which Smith had consented to Party A acting as it did was less than it might have been.

Suppose a majority of citizens had voted for Party A on the understanding it would stop the construction of the dam. Then I think we would say Party A’s claim to legitimacy was not as strong as ideally it could be.

What this brings out is that if voting is to confer what we might call ‘full legitimacy’ on the winner of an election, then voters need to be guided in the way they choose to vote by beliefs that are true. We can now glimpse how the presence of too much inequality in a society can threaten the ability of democracy to confer fully legitimate power on the winners of elections.

One person has more epistemic power than another if they can get the other to believe what they – the more powerful person – want them to believe, rather than what is true. If a person or other agency with great epistemic power persuades enough voters of the truth of something that is false, then the winners of an election might get in because people were guided in how they voted by a false belief. And, in such a situation, the winners of the election would perhaps have a reduced claim to legitimacy.

Global warming is possibly the most obvious example, at least in today’s world, of epistemic power being used to convince people of the truth of beliefs that are false. A significant number of people seem to have been persuaded that the scientific community is more or less evenly divided on the question of whether global warming is occurring. But this is, of course, very far from the truth. Almost all scientists believe in its reality. So, the question arises: why have so many come to believe something false? And the answer seems to be: some with greater epistemic power have used it to persuade others of the truth of something false.

Regarding the topic of global warming, the expertise dimension of epistemic power is particularly important. It might be used by one person to get another to believe something false. Suppose, for example, a highly sophisticated but contrarian climate scientist and an open-minded but scientifically untrained lay person sat down together to discuss whether global warming was real. The scientifically untrained lay person would be unlikely to influence the scientist. However, if the highly trained but contrarian scientist were to try to get the lay-person to believe global warming was not real, they might well succeed. In such a situation, inequality in the expertise dimension of epistemic power would be used to get another to believe something false. This might threaten the ability of elections to confer legitimate power.

Global warming is possibly the most obvious example, at least in today’s world, of epistemic power being used to convince people of the truth of beliefs that are false.

Suppose a voter does not wish governments to harm the environment or endanger the welfare of future generations. If they were persuaded of the reality of global warming, they might be reluctant to vote for a party that did not intend to do what they could to stop it. But, if they were persuaded global warming was not taking place, they may be quite happy to vote for a party proposing more coal mines or a reduction in renewable energy.

Suppose a party proposing more coal mines and fewer renewables wins the election. Would they thereby have legitimate authority to proceed with more coal mines? Again, it seems they would have legitimate authority only in a limited or qualified sense. If people voted for the party on the understanding that the party did not harm the environment, or that it looked after the interests of future generations, then the party’s subsequent actions would not seem to be fully democratically legitimated. In this way, high levels of inequality in epistemic power can endanger the ability of elections to confer fully legitimate power.

Another virtue that has been suggested for democracy is that it makes possible the removal of bad leaders without bloodshed. But similar difficulties arise for this suggestion. If voters are to remove a bad leader from power, they need to know whether the leader is performing well or badly. And, clearly, in order to do this, they will need to have true beliefs about what the leader is doing.

Again, the presence of too much epistemic inequality in a society can interfere with this. Those with great epistemic power can get others to believe what they would like them to believe, rather than what is true. If people are guided in the way they vote by false beliefs, then they might keep in power rulers that are performing badly and remove rulers that are performing well. Too much inequality in epistemic power interferes with the ability of democracy to remove bad rulers.

Another virtue that has been claimed for democracy is that, under certain conditions, it will lead to decisions that are probably correct. More specifically, it has been argued that even if the chance of each individual voter making the correct decision is only slightly better than 50/50, if a sufficiently large number of people vote then the majority result is very likely to be correct.

However, this argument for democracy is based on the assumption that the chance of each individual citizen making the right decision is at least slightly better than 50/50. And, of course, this need not be the case. It is possible the typical individual citizen might be more likely to make the wrong decision than the right one. And so, once again, we see how the presence of too much inequality in epistemic power can endanger the desirable functioning of democracy. If those with greater epistemic power convinced others to believe things that were false, then the ability of democracy to lead to decisions that were probably correct would be undermined.

Another argument, or family of arguments, for democracy appeals to the fact that, prior to voting taking place, very large numbers of people participate in discussions of matters affecting the community. Nowadays, with the internet and other forms of communication, there might be millions involved in the discussion. This involvement of so many people means a wide variety of ideas and values and perspectives are brought into the discussion. And so, it has been argued, this means the quality of the rational discussion leading up to a democratically-arrived-at decision can be superior to discussion that is not so broadly inclusive.

However, this argument for democracy is also undermined by the presence of too much inequality in epistemic power. If one person, or a particular group, has much more epistemic power than the others, they can use it to ensure their particular perspective dominates discussion. And, if this happens, then the expression and comparison of a diverse range of views which, ideally, ought to precede voting will not take place. And, so, the virtue that has been claimed for democracy – that it is a means by which decisions are arrived at in the light of comparison of a wide range of views – is lost.

In conclusion: inequality in a variety of forms – of expertise, of power of being heard and of prestige – endangers the ability of democracy to work as we would like.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Tom Seger on Unsplash.