This article is published in two parts. You can read Part 1 here.

Despite George Orwell’s Politics and the English Language, there has been a constant battle between rational and comprehensible language, and obfuscation and propaganda. The questions he raised are doubly pertinent in an era which has witnessed a new fall of rationality in language.

Marten Scheffer, Ingrid van de Leemput, Else Weinans and Johan Bullen address the issue in a PNAS paper, arguing that “the surge of post-truth political argumentation suggests that we are living in a special historical period when it comes to the balance between emotion and reasoning.”

The methodology they used was to analyse language in millions of books covering the period from 1850 to 2019 in Google Books. They found that the use of words associated with rationality, such as ‘determine’ and ‘conclusion’, rose systematically after 1850, while words such as ‘feel’ and ‘believe’ declined in usage.

The pattern reversed in the 1980s, with the change accelerating around 2007. The pattern was common to both fiction and non-fiction books. To check it wasn’t just a product of books, they found the same results in a similar analysis of the New York Times for the same period. “All in all, our results suggest that over the past decades, there has been a sharp shift in public interest from the collective to the individual, and from rationality toward emotion.”

They confess that inferring the drivers of this pattern remains speculative, as language is affected by many overlapping social and cultural changes, rapid technological and scientific changes, such as the arrival of the internet, and events such as financial crises. Nevertheless, they argue that getting the balance right “is urgent, as rational, fact-based approaches may well be essential for maintaining functional democracies and addressing global warming, poverty and the loss of nature”.

Other research suggests people are finding it harder to discern what is true and what is not. Gordon Pennycook et al (2021) report in Nature that they showed 36 headlines to 1,000 experimental participants. Half of the headlines were true. Some favoured political left positions; some right. Others were asked which headlines were accurate of real events.

Most people had no trouble distinguishing between truth and lies. But, when asked which they would share, they ignored the difference and happily shared headlines which matched their political views. Pennycook, in a separate study, found that fake news is often shared not because of malice or ineptitude but because of impulse or inattention.

What about the impact of partisan media? Andrew Guess et al (2021) say: “Popular wisdom suggests that the internet plays a major role in influencing people’s attitudes and behaviours related to politics”. While greater exposure to partisan views can cause immediate but short-lived increases in website visits and knowledge of recent events, they found little evidence of direct impact on opinions. Consistent with other research, they found the real impact to be a “lasting and meaningful decrease in trust in the mainstream media”.

Matteo Cinelli et al (2021) looked at content on controversial subjects, such as gun control, vaccination and abortion, from various social media platforms. Their results “show that the aggregation in homophilic clusters of users dominates online dynamics. However, a direct comparison of news consumption on Facebook and Reddit shows higher segmentation on Facebook.” In short, the echo chamber is reinforcing the tendency of people to seek out or be attracted to people like them.

If you are concerned that Twitter algorithms make it a right-wing plot, a study by Ferenc Huszar et al (2022) found the “mainstream political right enjoys higher algorithmic amplification than the mainstream political left”.

What about the role of influencers? Amy McDermott (2021) looked at a number of papers on the role of influencers and came up with some interesting findings. The people who spread new and controversial ideas may not be high profile. Rather, ideas spread fastest among those embedded in tight-knit groups with connections to other tight-knit groups.

In regards to informal political communication, Stefano Balietti et al (2021) found that informal discussion with peers could increase trust in democracy and improve understanding of self and others. “However, these benefits do not often materialise because people tend to shy away from political discussions and because friendship networks rarely expose highly divergent political views.”

An Australian answer

In Australia, Professor Axel Bruns has begun a project that “addresses the drivers and dynamics of partisanship and polarisation in online communication”. Bruns is an Australian Laureate Fellow and professor in the Digital Media Research Centre at Queensland University of Technology. His laureate project continues the work he began with the 2018 book Gatewatching and News Curation: Journalism, Social Media, and the Public Sphere.

More recently, in the 2019 book Are Filter Bubbles Real? he found there was no evidence for the claims that ‘filter bubbles’ and ‘echo chambers’ were increasingly enclosing us all in ideologically pure information environments on digital and social media platforms.

Bruns envisages that his new project might cover a number of key dimensions of polarisation, including in the journalistic content produced by different news outlets, in the audiences accessing and engaging with such content, in public debates, on social media platforms and in the networks of interconnection and interaction on and across social media platforms.

“We’ll address the comparison between national political and media contexts in the first place by comparing antagonistic Anglo democracies (Australia, the UK, the US) with consensus-based European systems (Germany, Switzerland, Denmark) – but here too there is still some scope to include other contexts.”

This article was originally published on the author’s blog.

Author’s note: This article has been made possible by John Spitzer’s research in the publications PNAS and Science over the past year or so.

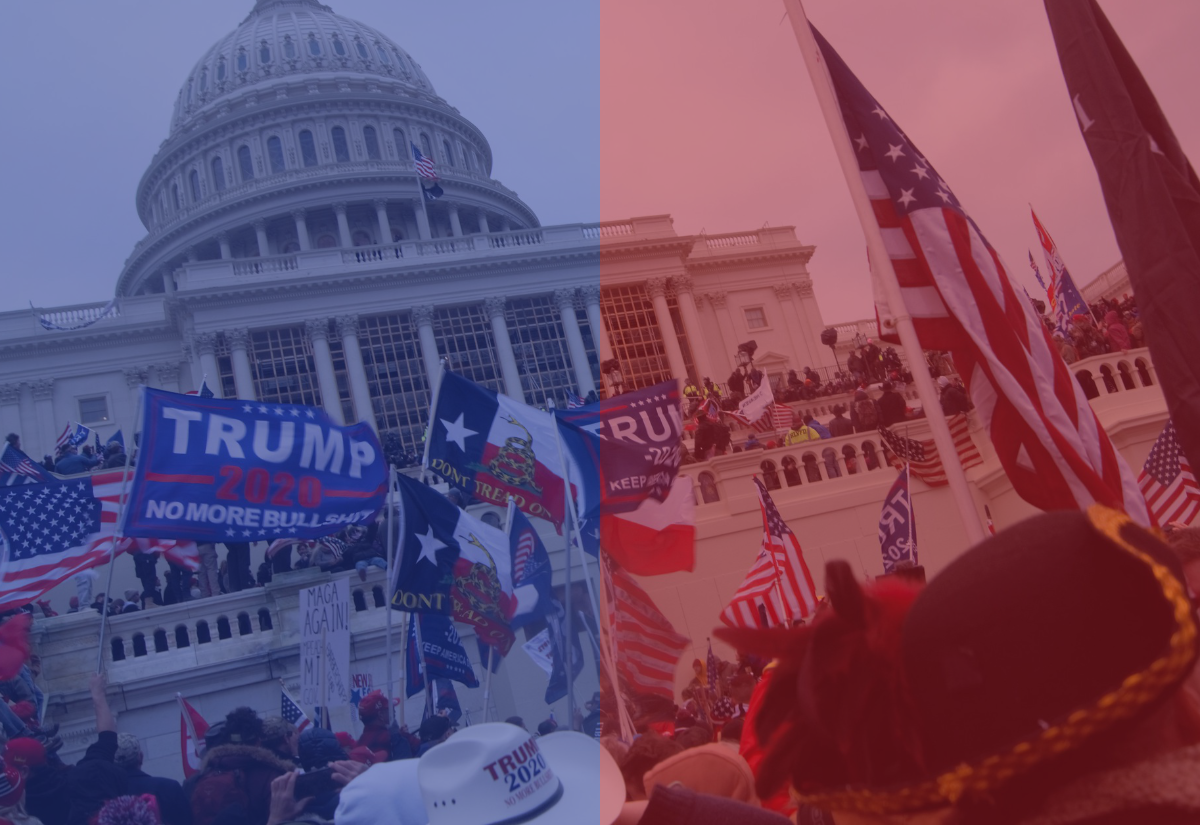

Photo by Tyler Merbler on Flickr (republished under Creative Commons)