Imagine that one day your neighbour knocks on your door and proceeds to tell you what to do. They might tell you how you can, or cannot, renovate your house. They might tell you how fast you are to drive your car. Or they might inform you that, from now on, you must pay them a certain amount of your income.

If our neighbour were to do this, I think we would tell them: “Go jump in the lake.” Yet, the government tells us to do these types of things. But most of us, at least, do not tell the government to go jump in the lake.

Why is this so? Why are we willing to do what the government says when we are outraged if anyone else tries to do it?

This is referred to as the problem of the legitimacy of political power. What, if anything, makes the power the government exercises over us legitimate?

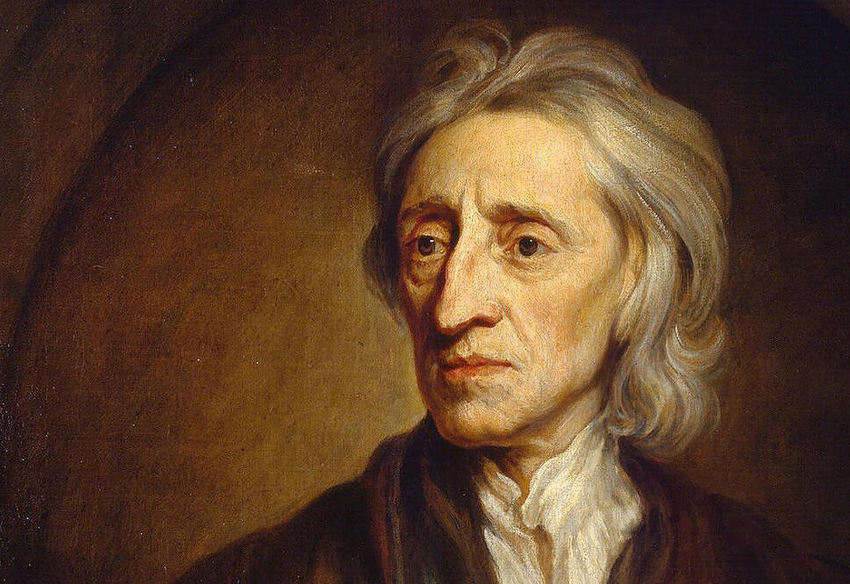

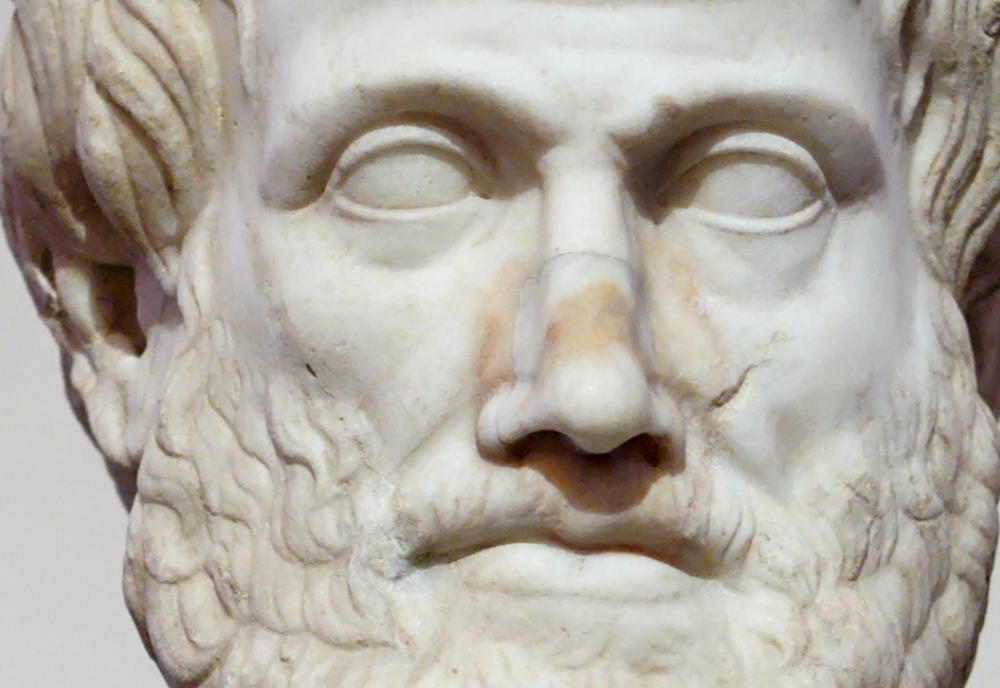

The philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) was concerned with this question. The answer he defended was: at least in a democracy an elected ruler has legitimate authority to exercise power over people because, in voting for the ruler, the people have given their consent to the ruler exercising power over them. That people have consented to being ruled over by the democratic government is often given as a reason that democratically elected power is morally preferable to authoritarian power systems.

There is, however, one obvious problem with Locke’s view. In any election, no party ever gets 100 per cent of the vote. In fact, often one party only wins by a narrow majority. For the sake of this article, let’s say a party gets into power achieving only 51 per cent of the vote, while the opposition receives 49 per cent.

But this raises a problem. The winning party will get to rule over everyone, including the 49 per cent that did not vote for that party. It seems that these people have not given their consent to being ruled over by the party that won.

So the question arises: what, if anything, gives the winning party the rightful authority to rule over the 49 per cent that did not vote for them?

Locke attempted to address this difficulty, as have many subsequent political theorists. But I think it is fair to say that, even to this day, the problem has no entirely satisfactory solution.

This difficulty need not be fatal for democracy. There are many factors that might make those who voted against a government more inclined to put up with being ruled over by those whom they voted against.

Perhaps most important of all is a belief that the other side won “fair and square”. If the losers accept that they lost a fair fight, they may be prepared to put up with it. But, if they feel the fight was not fair, they might respond rather differently.

Unfortunately, recent studies have found that, particularly in the United States, the factors that might help one side accept that the other won fair and square are in decline.

One recent survey by Pew Research found that a significant number of voters, on both sides of politics, are of the view that the issues they see as being of most importance have been omitted from significant public discussion. If one side wins without discussing what the other side regards as the most important issues, those on the losing side are not likely to see the winners as having won fairly. The losers seem unlikely to accept that the winners have a full claim to legitimacy.

The Pew survey also found that voters on both sides of politics believe that, recently, public discussion has become less fact-based. This is also likely to affect the extent to which the opposing side won fair and square. If the winning side only achieves victory by making claims that are empirically false, the losers will be less likely to see the winners as having a claim to legitimate power.

The survey also revealed that both sides see public discussion as having become disrespectful. If one side achieves victory by, for example, ridiculing, lampooning or libelling the other side, rather than by reason, argument and appeal to the facts, the losers will surely be less likely to see the winners as having won fair and square. They are also less likely, therefore, to see the winner as having an acceptable claim to legitimate power.

Perhaps most significantly, the different sides of politics have come to see the other as being simply unfit to hold power due to their personal and moral qualities. Again, it is hard to see how, under such circumstances, losers are likely to see the winners as having legitimate power.

All this adds up to a problem for democracy. If democracy is to work, those who end up on the losing side in an election must at least accept the legitimacy of the power of those that won. But a factor that contributes to this – a willingness to accept that the winners at least won “fair and square” – seems, at least in the US, to be declining.

As a result, the moral superiority of democracy over more authoritarian systems seems to be open to question.

Of course, this need not mean we have to acquiesce in the idea that democracy is no better than more authoritarian systems. But, if the moral superiority of democracy is to be maintained, then work needs to be done to ensure those on the losing side in an election have more persuasive reasons to accept the legitimacy of the victory of those on the other side.

Published on 21 July 2025.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Image: Portrait of John Locke by Godfrey Kneller (Wikicommons, CC).