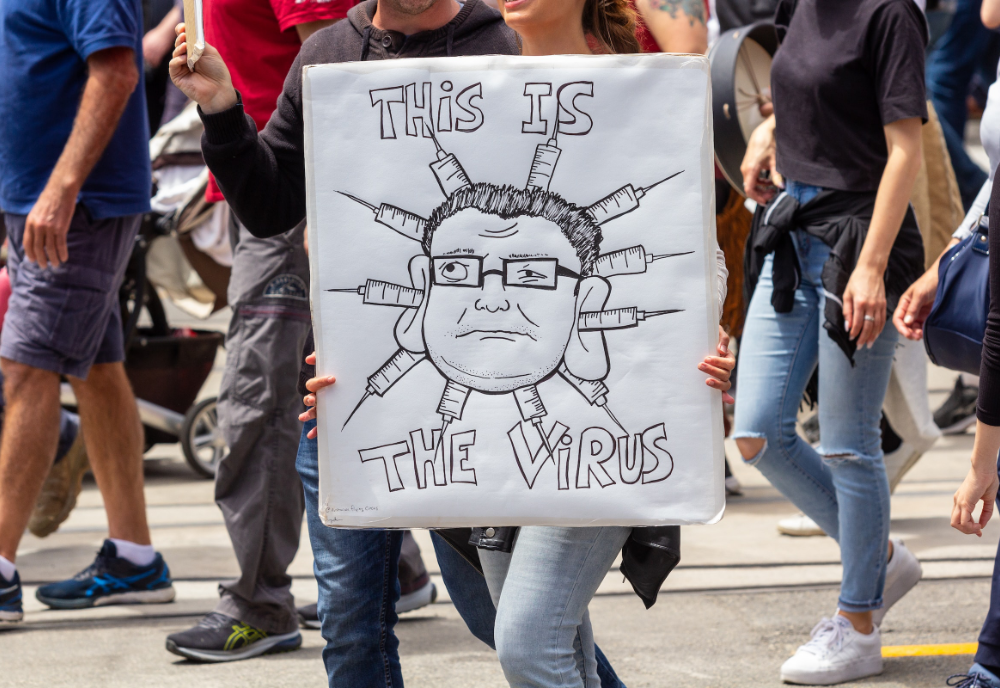

There has been much speculation about why the 2023 referendum on the Indigenous Voice proposal failed. Recurring themes include lack of bipartisan support, misinformation and lack of understanding by voters.

I suggest there may have been another stopper in the process worth considering: the voting system itself. How different would the final numbers have looked if voting in the referendum had not been compulsory? The outcome may or may not have been different, but the numbers might have told a different story.

Volunteering outside a booth was a first for me. While most people seemed tolerant of their voting obligation, I was surprised at the not-insignificant number of people clearly unhappy about being there. Perhaps they didn’t feel any connection with the issue. Or perhaps they just objected to being compelled to attend.

The outcome has sparked conjecture that the 2023 referendum might have been our last because it is just too hard to get the horse past the post. To succeed, a referendum proposal must meet the double majority test – the double bunger, you might say – lurking in section 128 of the Constitution. That is, the proposal must be approved by a majority of voters in a majority of states (territories excluded), and by a majority of all electors voting (territorians included). Only eight of the 45 referendums held to date have been approved.

Before we completely ditch the idea of referendums, we should look at other options. There is a school of thought that voting in referendums, or at least some of them, should be voluntary.

Most discussion about compulsory versus voluntary voting focusses on general elections. There is very little written about voluntary voting in referendums. Nonetheless, some of the arguments about compulsory voting in elections are relevant to referendum voting, too.

One objection frequently raised is that voluntary voting is counter to democracy. Words like ‘democracy’ and ‘compulsory voting’ get conflated. It’s been said, for example, that compulsory voting is a cornerstone of our democracy. Some might find this confounding because voluntary voting is common throughout the free world, such as in the United States, the United Kingdom and New Zealand.

In fact, Australia is one of just 21 democracies out of a total of 150 in the world with a voting system that compels all electors to vote. Digging down deeper, Australia is just one of nine democracies that penalises those who don’t vote.

The way we vote is not prescribed in the Constitution, so a referendum is not needed to change it. In fact, section 128 provides that voting shall take place “in such manner as Parliament provides”. Voting in federal elections and referendums was made compulsory in 1924 simply by parliament amending the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. In 1984, the provisions regarding the conduct of referendums were moved to their own home in the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 – the act that parliament would have to amend.

Of course, reverting to voluntary voting for referendums would involve a shift in the voter psyche. So the pulse of the nation would have to be taken first.

Parliament could make voting in all, or just some, referendums voluntary. Issues affecting the entire nation might require the compulsory vote of all its citizens – for example, the republic issue. Issues directly affecting only a small minority of people – perhaps the Voice proposal – might be appropriate for voluntary voting. It does not mean electors could not vote; it just means they could choose whether to vote.

While most people seemed tolerant of their voting obligation, I was surprised at the not-insignificant number of people clearly unhappy about being there.

In 1901, the six colonies were federated into one nation. How this came about was due in no small part to referendums held across the colonies between 1898 and 1900 – referendums in which the voting was voluntary.

Prior to federation, voting in the former colonies had always been voluntary (although not everyone had the right to vote). In 1893, the Constitutional Convention decided the future Constitution should be approved by the people. Each colony was tasked with holding referendums to get the people’s say-so.

The 1898 referendums held in New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia asked voters to approve the Commonwealth Constitution Bill. It failed because New South Wales, concerned they would be ‘disadvantaged’ under federation, required a quota of 80,000 yes votes and not just a majority of voters. That quota was not reached. The 1899 referendum, however, succeeded. Queensland joined the process and New South Wales only required a simple majority. The proposal was carried by a majority in each colony – a whopping 73 per cent total of those who voted. Later, Western Australia held a referendum after some gentle persuasion in 1900, although the Commonwealth Constitution Bill had been already enacted.

Following on, the first nine federal elections were held under voluntary voting, although compulsory enrolment was introduced in 1911. This meant that between 1911 and 1924, Australia had a combination of compulsory enrolment and voluntary voting (which New Zealand still has today).

Queensland was the first place in the Commonwealth to introduce compulsory voting. The then conservative government feared losing the 1915 state election because the unions were successfully amassing votes for the Labor Party. The government tried to level the playing field by introducing compulsory turn-out. Despite this, Labor still won.

There had been stirrings on the subject at the federal level, as well, and the connection between compulsory voting and voter turn-out in Queensland did not go unnoticed. Federally, voter turn-out had fallen to below 60 per cent after the war in 1922. Compulsory voting was successfully introduced federally in 1924. The bill introducing it passed with lightning speed through both Houses. Unsurprisingly, voter turn-out increased to 91 per cent at the 1925 election.

The other states then saw the rewards of compulsory voting and, between 1926 and 1942, legislated accordingly.

Case law has settled what satisfies the duty to ‘vote’. In Faderson v Bridger (1971), Barwick CJ said it involved attending a polling booth, accepting a ballot paper, marking it and depositing it in the ballot box.

Although there are now various options as to how this is achieved – take postal voting, for example – it is clear that simply attending the polling booth and having your name marked off does not. An actual ballot paper must be marked and placed in the ballot box. Informal and donkey voting, however, do satisfy the test.

Although the penalty for not voting is a fine, the consequences for failure to pay the fine can be steep.

What happens to those who fail to vote, such as conscientious objectors, for example? The objector receives a penalty notice telling them it is an offence not to vote without a valid and sufficient reason. They are invited to avoid court action by providing relevant details if they did vote, or, if they didn’t, to give a valid and sufficient reason why not. Alternatively, they can just pay a penalty of $20.

If the objector fails to take any of those actions, they would receive a second and then a third notice, warning them to pay $20 or face court. If they choose court, they will have to prove they had a sufficient and valid reason for not voting. Losing would mean a fine of one penalty unit which under section 4 of the Crimes Act is currently $275.

The law in relation to whether being a conscientious objector to voting constitutes a valid and sufficient reason for not voting is well settled. A magistrate would likely refer to the oft-quoted judgment in Judd v McKeon (1926) to indicate what would be a valid and sufficient reason:

Physical obstruction, whether of sickness or outside prevention, or of natural events, or accident of any kind, would certainly be recognized by law in such a case. One might also imagine cases where an intending voter on his way to the poll was diverted to save life, or prevent a crime, or to assist at some great disaster, such as a fire…

Clearly, being a conscientious objector would not meet this test, and a fine of $275 together with some court costs would be imposed. Failure to pay the fine, could result in a community service order being imposed, or even a short term of imprisonment.

Compulsory is compulsory is compulsory. This is one feature that definitely sits Australia apart from the vast majority of other democracies in the world. There are valid arguments for both kinds of voting in referendums.

Returning to last year’s referendum, we can only speculate about how voluntary voting might have affected the outcome. If there was a large number of people disinterested, misinformed or not informed, would they have decided not to vote if given the option?

I think it’s premature to think about relegating section 128 to the place where defunct pieces of legislation go and accept that for all time referendums are just too hard to win. I’d like to hear conversation and see research focus specifically on voluntary voting in referendums. And I’d like Norman Gunston to take the wheel on this one because he has always got his finger on the pulse as those of us with long memories know.

Published on 15 November 2024.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Stephan Ridgway (Flickr, CC)