People aren’t like rocks, and that has long been a problem for psychological scientists. If you are experimenting on a rock in the laboratory, it can be relied upon to have the same qualities or characteristics as it would out in the field where you found it.

But when investigating human behaviour, people in a laboratory situation can behave very differently to how they actually are in the wild. Context, then, is essential to understanding human decision making, but short of following someone around 24/7, accurately capturing this context has always been difficult. Until now.

The big data being regularly captured on all of us, through online services, phones, wearables and Internet of Things devices, is providing psychological scientists with the tools to indeed effectively follow around their subjects with relative ease. And this new ability to observe people in their natural habitats is telling us some interesting things.

In my research group, we have been using big data approaches to understand human long-term memory. Memory is particularly difficult to study in the laboratory because performance depends to a large extent on the lifetime of experiences people have before they enter.

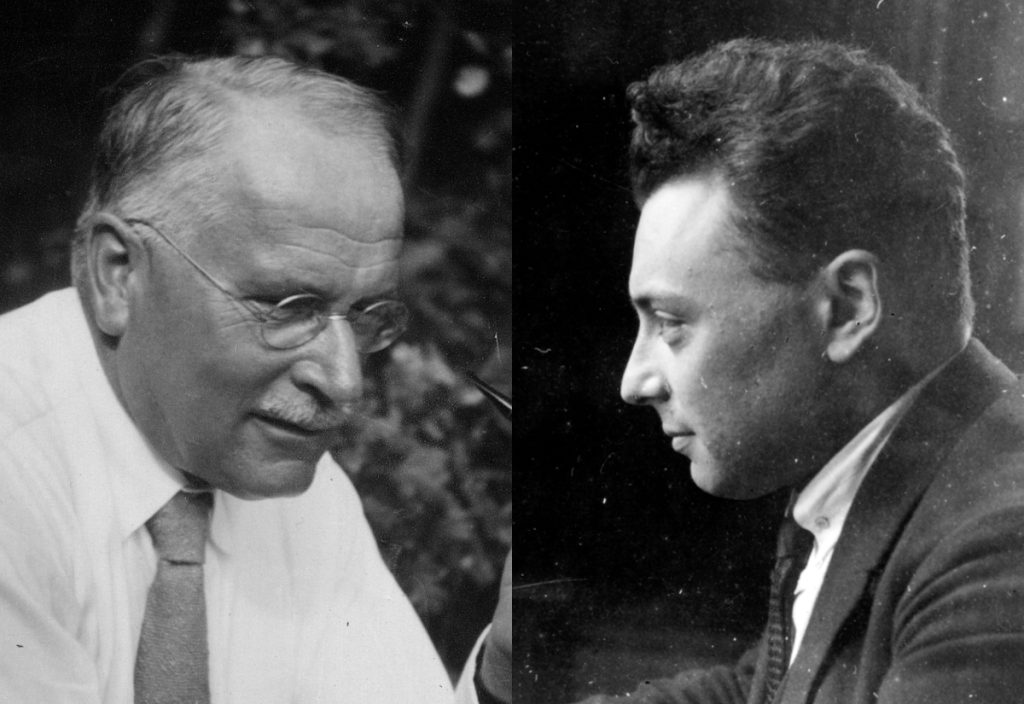

German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus (1859-1909) – the father of memory science – was well aware of the problem. In testing people’s memory, he needed something that would be unaffected by a person’s past experience and prior associations.

He came up with the idea of using nonsense syllables – like JOF and VEP. But it doesn’t really work. People are ingenious at turning nonsense syllables into acronyms or forming other associations.

These days, we use a range of stimuli – words, pictures, movie clips. These stimuli are more valid than nonsense syllables, but generalising from the laboratory to the real world is still very difficult. The laboratory is just too different from the circumstances of normal memory use.

So, in our research we started with a simple question. How well can people remember where they were at a given time?

We gave people a series of dates and times and had them select markers on a map to indicate where they had been. We used the record of locations collected by people’s phones to score whether they were correct. We found that overall, people are right about two thirds of the time. That’s useful to know if you are judging the accuracy of eyewitness testimony or you are involved in contact tracing.

However, we can go much further – we can take samples of people’s sound environments, record their movements, ask them how they are feeling, see who they have been texting and what they have been reading online.

The aim is to build up a comprehensive picture of their experiences so we can determine how people remember different kinds of information and which factors influence their ability to remember.

We now know that when people move – as measured by the accelerometer in people’s phones – it is a surprisingly good signal to us of when people believe an event has finished, that we can then test their memory on.

We also know that everyday emotions (as distinct from the intense emotions that people relate to important events and experiences) seem to influence people’s memories surprisingly little.

The use of big data is opening entirely new vistas in memory research, but I think this will be the tip of the iceberg. Big personal data will have a similar impact across all of psychological science, but only if people continue to be prepared to provide it.

Rocks are different from people in another important way. If I measure the chemical composition of a rock, pick it up a few times and watch how it falls, then share this data with friends and colleagues, the rock doesn’t care.

People do care, however, and with good reason. Increasingly, it feels like our personal information on the web is being used against us – from insidious advertising to cyber-attacks.

As cyber security consultant Troy Hunt pointed out on the PsychTalks podcast:

“Businesses are increasingly turning to data aggregators. These ‘middle men’ are capable of analysing personal data across multiple sources to build up a picture of who a person is and what their habits and preferences are. On the shadier end, there have been numerous services out there that have simply taken data breaches and sold the data.”

In this environment, where we give away so much of our data for free, it is challenging for people to take control of their own data and then make it available to others, whether for researchers or other interests.

However, services are emerging that are allowing people to “own” their data and potentially charge for it. Researchers need to adjust to the idea that they don’t own the data they collect on individuals, and cannot pass it on to others.

Governments are already making substantial changes in privacy law. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) are harbingers of what is to come.

Australia is currently going through privacy law reform and we can expect these processes to be ongoing as we transition from the wild west of data governance that exists in many contexts today into a more thoughtful and sustainable approach to data usage.

What this means is that, if we are serious about making substantial progress in psychology, we are going to have to renegotiate our contract with our participants. The old rules won’t work with such sensitive data.

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article. Story producers: Carly Godden and Andrew Trounson.

Photo by Victoriano Izquierdo on Unsplash.