When talking about ‘democracy’, ‘capitalism’ and ‘market economies’, many people confuse the terminology and the benefits that flow from these ideas while assuming they are necessarily tied in with each other.

A prime example of this can be seen in the article ‘In defence of democracy’ written by Carrick Ryan and published in the Rationale magazine in November. Ryan wrote a few things that I have problems with.

Before I address those issues, I will give a summary of his key points. In his essay, Ryan writes that democracy leads to countries being better places in which to live because they have economies that grow through creative destruction. In democracies, he says, innovation forces power structure adaptation, while in non-democratic countries the powerful suppress newcomers and challengers. He argues that history proves the rule: the more democratic a state, the more successful it is. He also claims that democracies provide individual freedoms while other systems do not. While our democracy is not perfect, he says, we need to fight to improve it rather than abandon it.

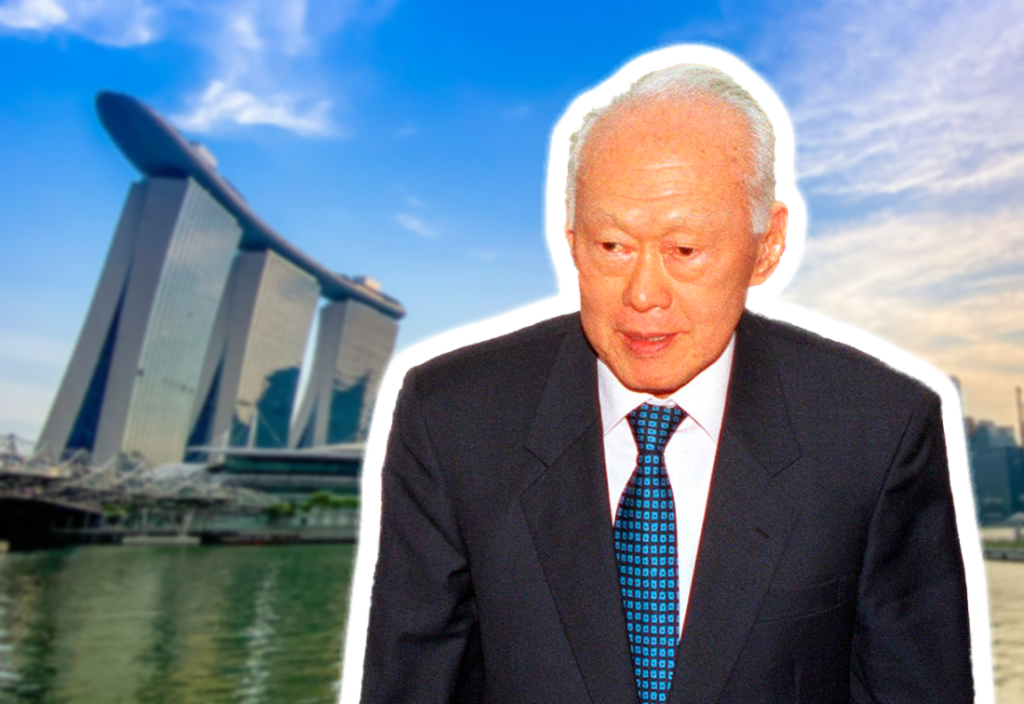

But democracy is a relatively small factor in determining the success or failure of many countries. It’s important to remember that most countries are relatively small. When a big player wants to bully them, it doesn’t matter whether a small country is a democracy or not.

We live in the age of the American empire. In my view, if you get in the way of American self-interest, you’re stuffed, no matter how democratic you are. On the other hand, if you can aid American self-interest, you’ll thrive, no matter how authoritarian you are. When I refer to American self-interest, I mean the American military industrial complex – the oligarchy that’s running the place.

For a lot of players in the world, their success, particularly for smaller countries, isn’t so much about whether they are democratic or authoritarian; it’s whether they’re on the good or bad side of the American empire.

I also think it’s misleading to connect democracy with capitalism, prosperity, innovation, market economics, personal freedom, health and happiness, et cetera, as if these things are all linked by some rule of nature and as if they all come hand in hand.

How power truly operates in the world is, in my opinion, vastly different from how Ryan painted it. The truth is that traditionally powerful countries have exploited smaller countries, their resources, their working class and the world financial system. Now, the opportunity for further exploitation has run out, and a reckoning is imminent. Capitalism requires growth. But those sorts of easy growth options have run out.

Neoliberalism the real threat to democracy

I know there’s a certain view around the world, from people like Steven Pinker, that everything’s okay, that Western liberal capitalist democracies have served us well and will continue to do so, provided we keep them in good shape. I really think rational Australians and others need to carefully look at that story and see if it’s true or not.

I agree with Ryan that democracy is in trouble. To rescue it, I think we need to better understand why it’s in decline.

Here, I’m going to refer to a book by Wendy Brown – In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West. According to Brown, we can blame neoliberalism. She says that neoliberalism is a political and moral project that puts individual liberty above the commons, the social good and all else. It demonises democracy because it attacks any idea of the state having the authority to interfere in individuals’ lives.

From the neoliberal point of view, democracy is a bit dangerous. It can allow the majority to limit the freedom of an individual, if enough people vote for it. Neoliberalism prefers personal freedom and puts up with an authoritarian undemocratic government as long as individuals are left alone to do whatever they want to do.

This point of view has permeated our culture. The erosion of the common good and society, along with the elevation of the individual, has sown the seeds of doubt toward democracy. That’s Brown’s analysis, and I tend to agree with it. If we want to fix the decline in democracy, we’re going to need to restore the social commons – the idea of society.

Authoritarian regimes can be liberal and capitalist

It’s worthwhile clarifying the meanings of key terminology used by Ryan. What is ‘democracy’? Essentially, it is power to the people, where everyone is treated equally. Everyone gets a vote and a say in how the society operates. And it’s not dictated to them by a small clique of unaccountable people.

It’s important to note that authoritarian states can conduct liberal societies where they don’t care what people do – for example, people can get divorced, gay people can marry and women can have abortions without the state interfering. It’s possible for an unelected authoritarian ruling group or person to have a fairly liberal interpretation of individual preferences. It’s just that you can’t vote the rulers out.

‘Capitalist’ and ‘market’ economies are different things. Capitalism is a recent invention. It has only occurred in the last 400 years or so, with the Industrial Revolution enabling individuals to accumulate so much wealth that they could live off the proceeds of their wealth.

A market economy is where the market, through the forces of supply and demand, works things out. In contrast to a market economy, a ‘command’ economy is where a central body tells people what to do and how often to do it.

Most people who consider themselves as capitalists are not practising capitalists. Even if you own a small business and you’re working in it every day because you have to, you’re just another wage slave like the rest of us. It’s just that you’ve got more pressure and accounting problems than the rest of us. You’re not a capitalist; you’re a believer in a market economy. You’re not a capitalist unless you’ve accumulated such wealth that you don’t have to work at all.

Authoritarian regimes can operate not only market economies but also capitalist economies. If you look at modern-day China, a lot of people are getting very rich running capitalist enterprises.

Moving up in the world

Ryan writes that democracies lead to countries that are better places to live in. In support of that argument, he suggests taking a look at the Human Development Index (HDI) and its scores given to nations based on a number of variables such as life expectancy, education and per capita income. He says that in the top performing 30 countries all but one are democracies. “Is this pure coincidence?” he asks.

In my view, a lot of countries in the top 30 would be doing very well because of circumstances beyond the fact that they are democracies. If you’re a former colonial power and you’ve accumulated massive wealth over hundreds of years from extracting wealth from colonies, and you’ve reinvested that in modern-day enterprises, then that can have much more to do with why you’re in the top 30 than the fact that you’re running a democracy.

It might also be a case of a particular country itself having vast resources per head of population – such as Australia or Saudi Arabia.

If you look at the HDI, it’s worthwhile considering which countries have been the big improvers in recent years. Of those that have moved up a lot of places in the past five years, the biggest improver – and by a significant margin – is China. It has moved up 12 places. Yet, it’s not a democracy. If your argument is to point to the HDI and the top 30 are all democracies but the biggest improver is not a democracy, what does it say about how the world is operating?

Also, if you’re looking at the top 10 improvers – Bangladesh, Bosnia and Herzegovina, China, Dominican Republic, Georgia, Hong Kong, Ireland, Kazakhstan, Maldives, Thailand – the only one rated as a full democracy is Ireland. So what does that say about whether you need to be a democracy to have a successful country?

If you look among the worst performers on the HDI list, you will find Venezuela. Despite holding democratic elections – said to be among the world’s most transparent by international election observers – the country has found itself on the wrong side of US interests. Clearly, other things are at play.

Innovation nation

Ryan also argues that democracies allow for innovation, which in turn makes their economies grow. He says innovation forces power structure adaptation among existing players. In non-democratic countries, however, the powerful are able to suppress the challengers. When it comes to producing innovation out of different systems, there’s no reason authoritarian regimes can’t produce innovation.

There’s a bit of a myth that innovation comes from the private capitalist sector. It’s a myth that needs to be exposed.

Economist Mariana Mazzucato developed a list of 12 key technologies that make smartphones work. There’s the hardware side of things – tiny microprocessors, memory chips, solid-state hard drives, liquid crystal displays, lithium-based batteries. Then you’ve got the software side – the Fast and Furious algorithm, internet, HTTP and HTML, cellular networks, GPS, touchscreen technology and Siri.

Most people would think, “Isn’t it amazing for Apple to assemble all those key technologies.” When Mazzucato reviewed the histories of all of these technologies, she found something striking: the foundational figure in the development of the iPhone was not Steve Jobs; it was Uncle Sam.

Every single one of these 12 technologies was supported in significant ways by governments – often the US government. Often, they came out of the military or government-funded universities. Good on Apple for putting it all together and packaging it attractively! But these inventions did not come from the private sector; they came from the public sector. Based on that example, an authoritarian regime (if it promotes big government) could potentially be more likely to produce innovation.

It’s also not the case that innovation is so readily accepted in Western democratic capitalist societies. Many modern companies today don’t have the money for innovation spending. They prefer to steal ideas and copy off each other.

There’s a huge advantage for big existing players in any industry, and it’s very difficult for small ones to crack through. What you will find is big players put up barriers to entry to stop small players coming in, even if the new competitors have a slightly better product. If that doesn’t work, a big player will often buy up a smaller new player and either discard its innovation, thereby preserving the big player’s existing product, or utilise the innovation but charge monopoly prices, wiping out the economic benefit for you and me and keeping the economic benefit for itself.

You only have to look at inequality graphs to see that, even if innovation actually transfers through to product, it’s not so much that countries experience economic growth, it is the private enterprises that benefit. And these private enterprises are probably shifting the profits offshore anyway!

While I share Ryan’s concern about the future of democracy, I disagree with his take on the success of democracies and the way power works in the world. For a lot of counties that are doing well, it’s likely there are historical factors that they’re continuing to benefit from. If you look at countries that are doing poorly, it’s likely there are other factors involved for why life is not so great. It’s not simply a matter of whether or not they are democracies.

Photo by Caleb Perez on Unsplash.