Suppose you were in an English language class and your teacher or professor insisted that the use of language in all old books, going back to Anglo-Saxon poetry, had to be changed because outdated usage was objectionable and offensive. And suppose that, instead of applying yourself to learning the archaic words and syntax of your ancestors, they insisted you should fault them for not having written as we do in the 21st century.

Wouldn’t that seem outlandish and strange as an approach to the study of the language? Yet, we seem to be facing a tidal wave of pedagogy which takes this approach to history and to language in the name of ‘decolonisation’ and the entrenchment of racial, sexual and gender diversity.

It’s all quite bewildering if you’ve grown up regarding the difference of the past from the present as the whole point of studying – and learning from – the past.

Frank Furedi, in The War Against the Past: Why the West Must Fight for Its History (2024), has offered us a trenchant survey of how what he calls ‘presentism’ has come to infect our classrooms and professional institutions over the past generation or two. This is a crucial facet of what is often referred to as ‘the culture wars’.

Those who see the ‘decolonisation’ and ‘diversity, equity, and inclusion’ (DEI) movements as desirable correctives to the status quo will find his arguments confronting. Those who feel confronted by just those movements are likely to feel confirmed in their irritation. But the matter is consequential and warrants a close, not presumptive, reading.

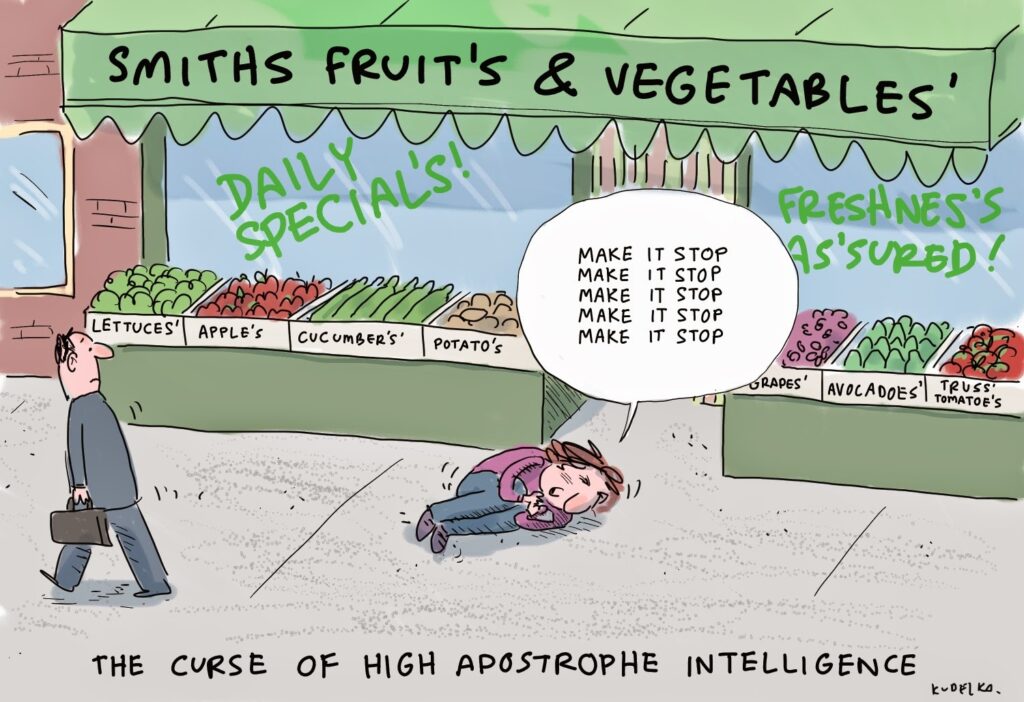

His chapter headings convey, as chapter headings should, the approach he has taken. There are seven: What is the Past?; The War’s Long Gestation; The Ideology of Year Zero; The Present Eternalized; Identity and the Past; The Struggle to Control Language; and Disinheriting the Young from Their Past. Taken together, they provide a disturbing introduction to what, at times, feels like a Western version of China’s fearsomely destructive Cultural Revolution of 1966-76.

If all this hasn’t caught your attention yet, his is an unsettling and thought-provoking clarion call.

When, for example, Furedi points to educational authorities or publishers, pseudo-scholars or polemicists insisting that Cleopatra was ‘black’, that Aristotle ‘stole’ his erudition from the ‘African’ Library of Alexandria (which didn’t exist in his time and was actually inspired in significant measure by his private library), when they issue ‘trigger warnings’ about the ‘outdated’ language or social views of authors from Ovid to Roald Dahl, from Immanuel Kant to Virginia Wolf, we know we are in ‘Maoist’ territory.

With reference to the evolution of laws, manners and customs in the work of Norbert Elias, Furedi centres us all on “the civilising process” and the need to comprehend the past and see how, like Isaac Newton, we “stand on the shoulders of giants” who have enabled us to develop, through trial and error, to our present, imperfect, ways of being and interacting, both with one another and with the natural world.

To paraphrase Karl Marx’ famous final thesis on Feuerbach, the point is not to change the past but to understand it.

Edith Hall, in Epic of the Earth: Reading Homer’s Iliad in the Fight for a Dying World (2025), has given us a dazzling exercise in doing this, with deep contemporary relevance, in her brilliant reframing of Homer’s Iliad from an ecological point of view.

That epic, of close to three thousand years ago, has had enormous cultural impact, she says, not only in classical Greece but around the world. And is still very much alive now.

Does she rant against the social practices or language used by the poet: slavery, concubinage, militarism, blood-lust? No. She observes them dispassionately. She reflects on them.

Above all, she draws our attention to the implicit attitudes towards the natural world as an infinite resource in the Bronze Age world. She finds in this the seed of our war against the natural world, our exhaustion of it, beginning with the massive deforestation and its destructive consequences, occasioned by Bronze Age farming, smelting, ship-building and funerary practices.

It’s a bravura performance, grounded in first-rate knowledge of the text and the sources. That’s the way to do it!

It’s all quite bewildering if you’ve grown up regarding the difference of the past from the present as the whole point of studying – and learning from – the past.

Her book is up there with the late Mark Elvin’s magisterial environmental history of China, The Retreat of the Elephants (2004), which shows all the same things happening in Bronze and Iron Age China. It also sets the stage for such wonderful parodies of Homer as Natalie Haynes’ A Thousand Ships (2019), which brings to life the Homeric world as seen through the eyes of its women characters – dare I say its female characters.

But to circle back to where we began, as it were, Laura Spinney’s study of the origins and spread of the Indo-European languages – in Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global (2025) – is a splendid scholarship for a globalised world.

It is a bracing contribution to an inquiry that dates back to the eighteenth century, when William Jones (1746-1794), working as a colonial judge (heaven forbid) in British Bengal, realised that Sanskrit had a remarkable amount in common with Latin, Greek and English itself. This was a big step in the direction of a global humanism and a wider global history – much of which is now flourishing.

Proto is a wonderful read, both rigorous and enlightening. It sits alongside such wonderful works on the subject as David Anthony’s The Horse, the Wheel and Language (2007), or Luigi Luca Cavalli Sforza’s Genes, Peoples and Languages (2001).

Spinney’s conclusion pivots on the recovery of knowledge about late Stone Age burial sites in Ukraine, from the ruin wrought by the Russian invasion of 2022. It’s not a polemic. It’s a testimony on behalf of history against war. It’s a beautiful read, and there are no trigger warnings.

She tells us, with scrupulous attention to what has been painstakingly pieced together by many scholars and linguists, of how Indo-European became the single largest language family on the planet.

Question: should she have engaged in an ideological and cultural critique of this having happened – in ‘apologies’ for the ways in which it displaced older languages? She is not ‘imperialist’. She is a historian. And what she shows us is absolutely fascinating. Fresh to the subject? Read Spinney.

Published 10 October 2025.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Image: Jr Korpa (Unsplash)