In February 2018, as head of the Royal Australian Navy’s Chaplaincy Branch I attended an international Chiefs of Chaplains conference in Helsinki, Finland. It was a fascinating experience.

I remember one conversation with a participant – a fellow runner and the then US Army’s Chief of Chaplains. He mused that it would be difficult to conceive that anything like today’s chaplaincy model would exist if the US Department of Defence were starting over again with a clean sheet of paper. He was, and continues to be, right.

When more than 60 per cent of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) – or, more tellingly, when 80 per cent of new recruits – have no religious affiliation, why would you have religious clergy as the most accessible and available support to ADF people?

To put it bluntly, most of these service personnel who say they are not religious simply have no interest in religion or do not see it having any relevance in their lives.

In the ADF today, there are 160 full-time and 150 part-time clergy providing, essentially, wellbeing support to an increasingly non-religious workforce.

To become a chaplain in the ADF, you need a degree in theology – for the vast majority of them, Christian theology. This includes expertise in Greek and Hebrew, the Old and New Testament books of the Bible, biblical theology, church history, hermeneutics, homiletics and apologetics.

Chaplains will also need to be ordained and have at least two years experience in a church as a pastor, priest or minister. As we know from Neil Francis’ Religiosity in Australia series, churches are not a cross-section of the general community.

Church attendance in Australia is disappearing through the floor, even among those who define themselves as Christian. A shrinking proportion of Australians attend church regularly. And younger Australians are even less likely to attend.

So let this sink in: the ADF’s most visible and primary wellbeing practitioners are religious clergy with degrees which have so little relevance to the modern workforce. And these people’s church experience, gained among fellow religionists, does not even come close to resembling the lives of most women and men who join the ADF today.

It is not difficult to agree with the former Chief of Chaplains to the US Army. It is, indeed, unlikely that anyone would get away with assembling the current religious chaplaincy model today.

Navy’s ‘lightbulb moment’ a couple of years ago has set it on the path to modernising its chaplaincy model, with the introduction of secular Maritime Spiritual Welfare Officer (MSWO) roles. Navy’s forward-looking senior leadership has embraced this reform.

However, the Army and Air Force appear to be resisting the need to modernise their chaplaincy model. And this is to the detriment of its mainly young workforce.

So let this sink in: the ADF’s most visible and primary wellbeing practitioners are religious clergy with degrees which have so little relevance to the modern workforce.

When questioned about why the Army was not following Navy’s lead on non-religious support, the retort of one senior Army officer, in defending the current religious model, was: “Think about it like this: who do you want to bury you on the battlefield?”

There is an underlying assumption here, and it needs to be challenged. It is a view that religion is a vital support to morale on the battlefield. It is commonly expressed as, “There are no atheists in foxholes.” Meaning that somehow, when the darkness and dread of battle descends, and the level of fear increases, people get religious – hence the need for the padre.

There are a couple of problems with this view. First, it is not true. There are atheists and religiously disinterested humans in foxholes and on battlefields all around the world. There is not one shred of evidence to support the view that combat commonly causes people to turn to God. If it were true, one would expect to see a spike in religious adherence in those who have deployed on active service. There is no spike because it isn’t true.

The second problem with the view raises some bigger issues for the ADF. If it were true that soldiers need religion on the battlefield, then why does the ADF only provide one solution to the fearful atheist’s dilemma?

Of the 160 full-time ADF chaplains, they are overwhelmingly Christian. There are a handful – fewer than five full-time – religious clergy from other religious faiths. But the chance of seeing anything other than a Christian padre on the battlefield is almost zero.

Australia is a pluralistic society and some of the fast-growing religions are not Christian. So what role does the ADF have in choosing winners on the battlefield? Or, to put it another way, what business does the ADF have in privileging the Christian faith over the rest?

Where is the diversity in this overly Christian capability? Why isn’t there a group of multi-faith military religious leaders, trained and ready to deploy, allowing the religiously confused to seek out a religious professional of their choosing rather than the imposed Christian solution?

The third problem relates to the prevailing view that you need God to be good. Chaplains often push the line that religion is necessary for an ethical life and that without faith it is impossible to be good.

Aside from being an arrogant assertion, a number of close inspections of religious communities in recent years have pulled the rug from under this line of reasoning. Take, for example, the findings of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse or the study that showed the rate of family and domestic violence being higher among Sydney Anglicans than the general community.

There is no good reason to believe that religious faith inclines a person to a higher moral standard than a humanist, atheist or agnostic.

The ADF is crying out for a wellbeing model fit for the current workforce. No matter which way you cut it, the ADF workforce is less religious than ever. Outside of the ADF, today’s personnel would be highly unlikely to show up on the doorstep of any priest or pastor seeking help when life gets difficult. This is a generation which is far more comfortable to confide in friends, their GP, family members or seek out a counsellor or psychologist.

Chaplaincy is a discretionary service. No one is required to go to a chaplain. To be effective, Defence must work hard to ensure there are as few barriers as possible to using the service.

It is completely unsurprising and completely uncontroversial to say that religion is a barrier to care for many people. As members approach a chaplain and see that cross on their lapel or on their chest, most people will be reminded of the churches’ hang-ups and negative views around sex, same-sex marriage, divorce, abortion and their institutional child-abuse problem. And that is the case, regardless of what the individual chaplain actually believes to be true.

Individuals may also experience a general discomfort that this clergyperson is judging them and thinks their lifestyle is sinful. Some people may think they are not a complete person unless they convert to a religion.

This discomfort with religion in general, and the clergyperson in particular, is unhelpful and a serious barrier to service personnel accessing wellbeing support.

So why is it so difficult for some senior Defence leaders to see the problem? Defence is a very conservative organisation. Its leaders are shaped over the course of a lifetime career. Most senior leaders have strong sympathies with, or are involved with, religious faith. They have fond memories of chaplaincy and religion.

As members approach a chaplain and see that cross on their lapel or on their chest, most people will be reminded of the churches’ hang-ups and negative views around sex, same-sex marriage, divorce, abortion and their institutional child-abuse problem.

While senior leaders have few issues when it comes to evolving and updating military capability – there are no longer Mirages, Leopard tanks, Charles F Adams destroyers or Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates – religious chaplaincy continues largely untouched and unaffected by trends and the changing needs of the current workforce.

Additionally, the task of reforming the capability is made more difficult by the Religious Advisory Committee to the Services (RACS). This committee of bishops or religious group equivalent is appointed by the minister and funded by Defence. The committee endorses religious clergy to be ADF chaplains and also believes that it has some sort of oversight duty towards ADF chaplaincy services.

One example highlights the problem. The Anglican member of RACS, Grant Dibden, told Anglican News in early 2020: “I want to encourage the chaplains to make disciples who make other disciples.” Also, on the Defence Anglican website in 2021, he said: “Our heart is to minister in the Australian Defence Force, to be Ambassadors for Christ, and to represent the Anglican Church in this complex secular context. We do this in Jesus’ name.”

Making disciples? Representing Jesus in a complex secular context? Well, that’s one take on providing wellbeing service! But it’s not one that I think most ADF members would be comfortable with. And this is a committee that has direct access to the Chief of the Defence Force and the Minister.

The ADF needs to engage its workforce to determine how to meet its needs. What I find astonishing is that those most likely to access the services of a chaplain have never been consulted or asked about their preferences for this service.

Reform of the chaplaincy capability must be based on best-practice insights from human services and mental health research. It should be human-centred, trauma-informed and accessible to everyone.

The ADF needs to charge a senior and neutral wellbeing capability person to lead the reform effort. The task cannot be entrusted to a person who is enmeshed in the religious mission of chaplains or the churches.

To ensure its success and effectiveness in the military, the practitioners who are employed in a new wellbeing capability must wear the same uniform, work alongside and deploy with the service personnel that they care for – just as the chaplains currently do. Serving ADF personnel need to view these people as “one of us”, rather than some outside group – like every other support service is currently viewed.

A new wellbeing capability must be genuinely secular. Human service qualifications and experience should be the gateway into the capability, rather than one’s religious faith group affiliation and endorsement. When you visit a GP, dentist, psychologist or counsellor, it shouldn’t matter that the caregiver is Anglican, Buddhist, Muslim or atheist. The same must be true for a wellbeing practitioner. I only need to be reassured that they have the appropriate education, training and experience to provide appropriate wellbeing support.

This last point is a big one. The Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide is asking the hard questions about qualifications, skills and experience of all practitioners in Defence, except chaplains.

Finally, the term ‘chaplain’ carries baggage. If the primary reason for its existence is to provide wellbeing support, then call it the ‘Wellbeing Support Branch’.

I am not against Defence employing a smaller number of specialist wellbeing practitioners who are religious chaplains. There are good strategic reasons why Defence might do well to retain the religious specialisation. As we reach out in the Indo-Pacific, a religious chaplain can assist Defence in making connections with neighbours in our religious neighbourhood.

If the ADF is to succeed in looking after the wellbeing of its workforce and break free from the anachronistic legacy that is the chaplaincy model – it is, clearly, a relic from another era! – then reform has to come from outside chaplaincy itself. And, quite possibly, reform has to come from outside the ADF ecosystem.

It isn’t impossible for the whole of the ADF to reform its chaplaincy model, as the Navy has shown it can be done. But it cannot be left in the hands of the religiously inclined.

This is not an attack on religious faith. For those who see religious faith as important, I support their fundamental right to be supported in the way they wish. But, for the majority of personnel who do not identify as religious, the ADF has to get serious about a uniformed non-religious wellbeing support capability.

The mental health and wellbeing of our sailors, soldiers and airmen and women is of fundamental importance to our nation. They deserve a real-world support capability that is shaped to meet their needs.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

This article is based on a presentation to an RSA Webinar earlier this year. You can watch the full webinar here.

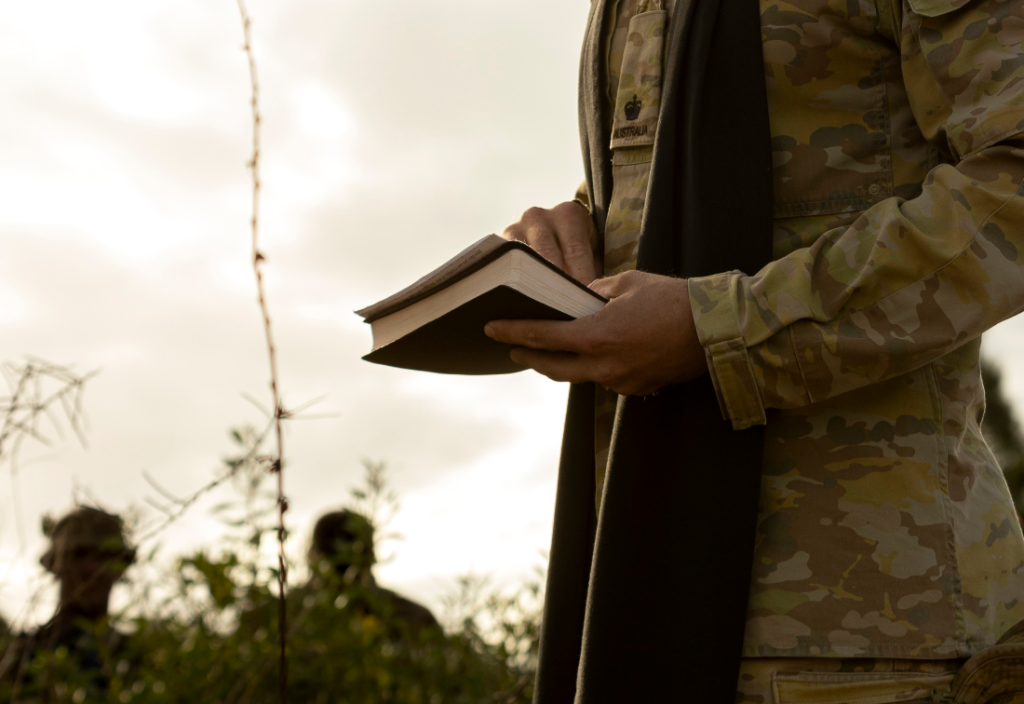

Photo by Department of Defence (Commonwealth of Australia).