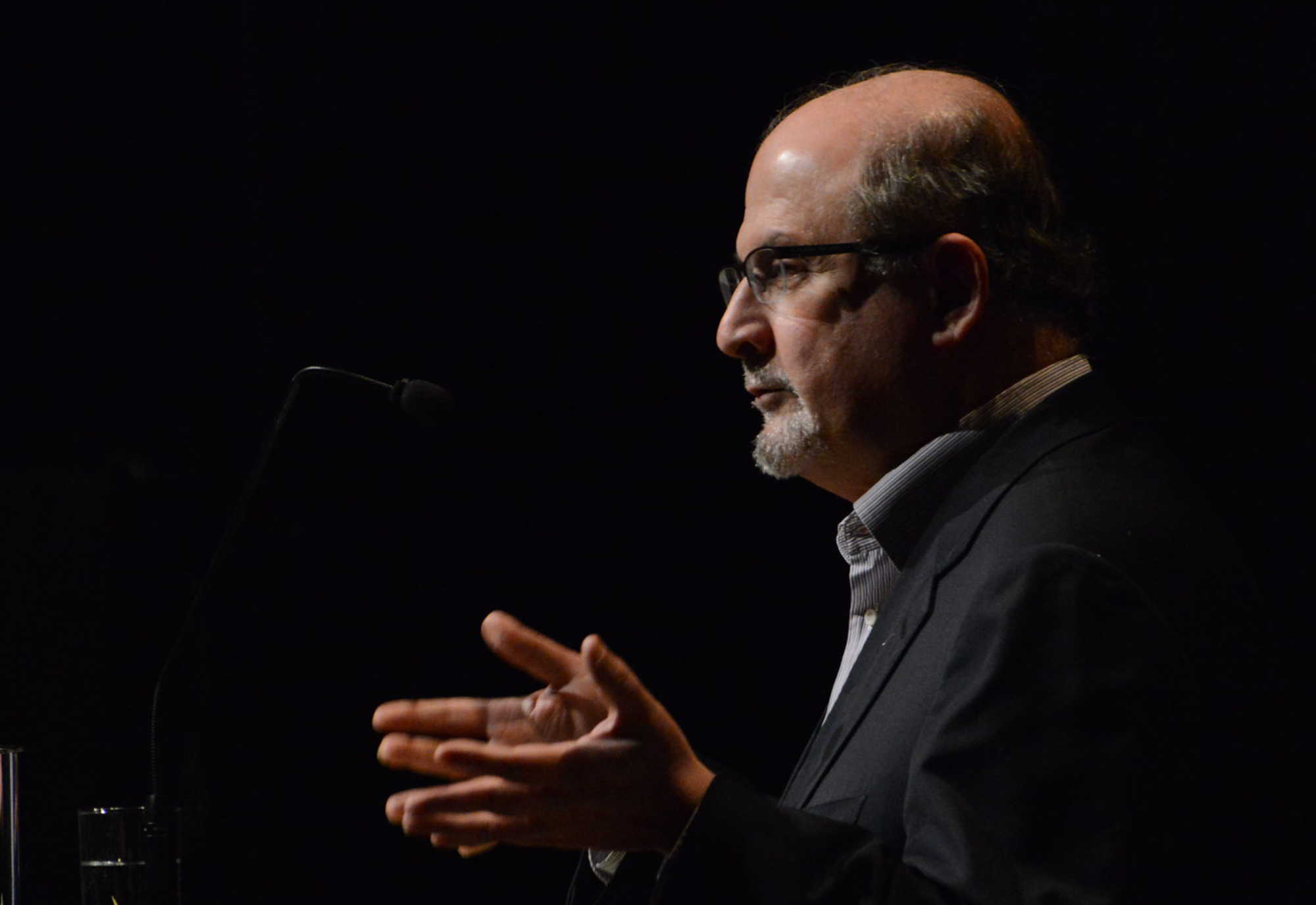

Salman Rushdie was assailed by 24-year-old Muslim fanatic Hadi Matar on 12 August as he was about to give a public lecture in New York. Matar stabbed him several times and also wounded the interviewer, Henry Reese, who was beside Rushdie on stage. The assault was denounced by many figures, including heads of state, around the world, as a direct attack on freedom of speech.

As is well known, the Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Rushdie in 1989, condemning his novel, The Satanic Verses, which had been published in 1988, as an offence against Islam. The fatwa called for Rushdie to be killed by any means and offered $3 million to the successful assassin.

Matar’s deed was hailed by the official and conservative press in Iran. Matar’s America-based mother, on the other hand, condemned the attack and declared she will never speak to her son again. There’s the difference between fanaticism and humanity.

Rushdie had lived in hiding under tight security for years after the fatwa, but with the passing of time things had slowly relaxed. Not, however, before Hitoshi Igarashi and Ettore Capriolo, the Japanese and Italian translators of The Satanic Verses, had been attacked, the former fatally in July 1991.

Even so, the venue at which Rushdie was to speak in August this year was regarded as safe, and the attack came without any immediate prior warning.

That said, in 2017 Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the current boss cocky in Tehran, had made clear that the fatwa had not lapsed. That was – and the attack is – a reminder that the problem of freedom of speech and expression raised by the fatwa remains very current.

Rushdie’s talk, ironically, was to have been about the United States as a safe haven for exiled writers – which, in general, it is and long has been.

What calls for emphasis is what exactly we understand by the term, ‘safe haven’. In response to the attack on his father, Zafar Rushdie, the son of the novelist, declared, “Free speech is the whole thing, the whole ball game. Free speech is life itself.”

Why would that be? Freedom of speech has, in fact, been something of a rarity historically. It isn’t a human universal. It has had to be fought for and hammered out. It is an explicit and avowed principle of only two phases of Western civilisation: the classical world of the Greek and Roman republics, and the modern liberal world. It requires protection under law and standards of civility that have in general been lacking almost everywhere. If we don’t understand it in those terms, we don’t understand it at all.

Freedom of speech has, in fact, been something of a rarity historically. It isn’t a human universal. It has had to be fought for and hammered out.

There have been calls by Muslim activists to dissociate the attempt on Rushdie’s life from Islam or Muslims. That’s understandable, except that freedom of speech is not something recognised under Islam or available to the peoples of Muslim states.

The fatwa against Rushdie did not come out of a blue sky. As we have seen around the world since 1979, when the Ayatollah seized power in Iran, criticism of Islam of almost any kind again and again triggers threats of violence and acts of violence.

What does it make sense to do in such circumstances? As it happens, when The Satanic Verses was first published it was banned in India, which is a majority Hindu country and a more-or-less democratic state. Indian leaders, starting with then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, reasoned that with tensions between Hindus and Muslims always a problem in the country, it would be undesirable to stir Muslim anger by allowing the book to circulate.

His reasoning was understandable, even prudent. But it points to the problem: there is a clear antipathy within mass Muslim culture – and not only among the occasional fanatic like Hadi Matar – to freedom of speech if it involves any criticism of, challenges to, or lampooning of, Islam. If we had that problem with Christians or Monarchists or Communists, we would see freedom of speech as under serious threat.

But these days we don’t. Why? Because within Western civilisation those issues have been faced down over several centuries and the principles of toleration and freedom of speech have been hammered out in both law and civil convention.

The principles at stake here were beautifully set out by Timothy Garton Ash in Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World, a few years ago. His book – as I pointed out in the foreword to my own book, Dictators and Dangerous Ideas, in 2018 – should be read and discussed as widely as possible. The matter is pressing.

And it’s pressing not simply because of Rushdie or militant Islam. It is pressing because freedom of speech appears to be under attack very widely right now. It does not exist in Xi Jinping’s China at all. It has been ruthlessly under attack in Putin’s Russia for many years. It has been suppressed in Erdogan’s Turkey and in Assad’s Syria, and is anything but robust in Mohammed bin Salman’s Saudi Arabia.

But it is also challenged by cancel culture and deplatforming activism in the Western heartlands.

How is it to be protected? By insistence on its practice and its legitimation. It’s heartening that in the wake of the assault on Rushdie, sales of his books shot up, including The Satanic Verses. The latter moved from outside the top 100 best sellers on Amazon to number 13 within days. Mirabile dictu!

But that is where the press is free – where freedom of speech is clearly protected. It needs protection globally. And the only way this can be systematically advanced is through the dissemination and active defence of the principles enunciated limpidly by Ash in 2017 – the same year that Ali Khamenei confirmed the fatwa against Rushdie.

What are his 10 principles? You can find them in his book, or in the foreword to Dictators and Dangerous Ideas. Both books are available from Amazon, though almost certainly not in certain countries, save in samizdat.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Fronteiras do Pensamento on Flickr.