While the nation takes stock to remember our Anzacs this week, we need to take a moment to think about how we can better support the current members of our Australian Defence Force (ADF).

The toll that military service has on our service personnel has long been acknowledged. The ongoing Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide, established mid-2021, has brought this into sharper focus. The hearings have heard some truly harrowing accounts of how ‘the system’ has let service personnel down.

As the Royal Commission has already heard, there are gaps in the support provided to veterans. And, when current and former ADF members fall through these gaps, the worst possible wellbeing outcomes can result.

One such gap may result from a poor ability to undertake early intervention and wellbeing triage while a member is still serving – an inadequacy that can partly be attributed to the ADF’s approach to chaplaincy.

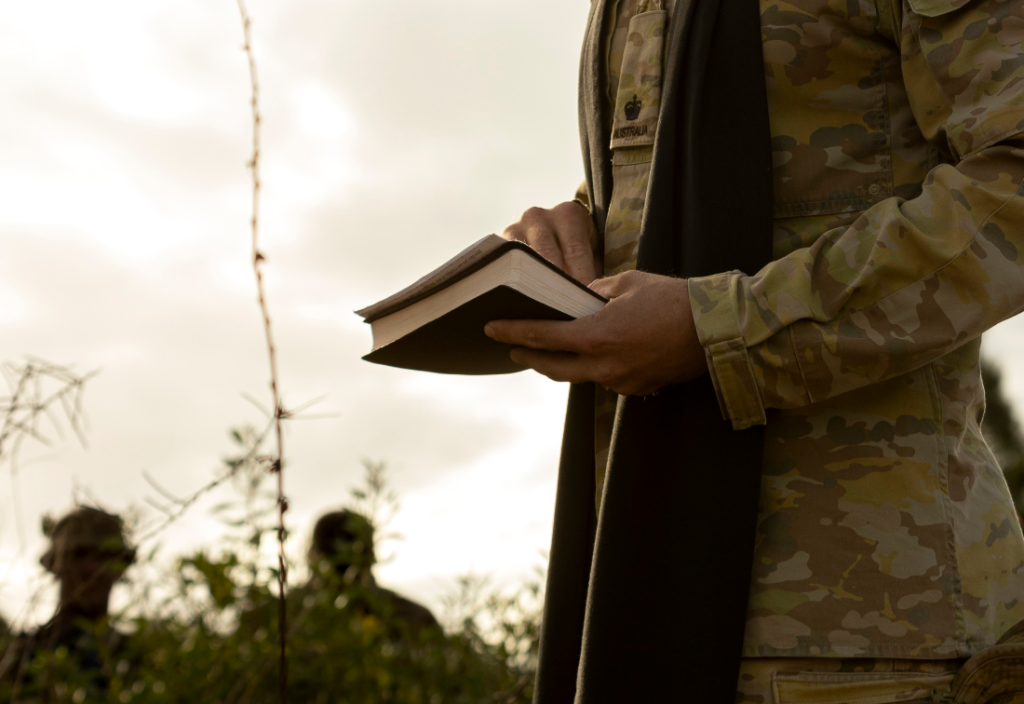

Currently, the ADF’s pastoral care and wellbeing approach, known more broadly within Defence as ‘chaplaincy’, is provided exclusively by religious uniformed chaplains, who are predominantly Christian.

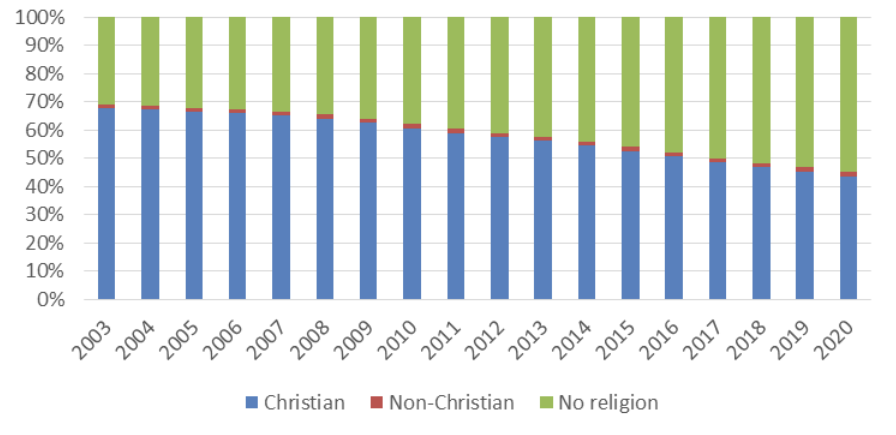

In results from the 2019 Defence Census, it was revealed that 56 per cent of full-time Defence members were not affiliated with any religion – up from just 31 per cent in 2003.

Religious affiliation from 2003-2020 in the permanent ADF.

There are signs that this trend will not slow down anytime soon. With an annual increase of between 1.5 to 2.5 per cent, it is estimated that the absence of religious affiliation among Defence members is now around 61 per cent. The proportion of ADF personnel with no religious affiliation looks certain to reach, and then plateau, at around three quarters of the Defence population by 2030.

This change in demographic characteristic is driven almost exclusively by young recruits aged between 18 and 24 years. It raises a serious question about the ADF’s ability to provide effective wellbeing support using the existing religion-dominated approach when a large and increasing majority of its members are not religious.

With the decrease of religion as an important factor in the lives of individuals, a transition to a secular needs-based model for providing the wellbeing support that Defence members deserve seems overdue and increasingly essential.

Without such a transition, Defence will reinforce and perpetuate an outdated perception of conservatism and risk a demise in social legitimacy with an ensuing inability to recruit for the future needs of the nation. It will also fail in its responsibility to look after the wellbeing needs of those who have chosen to defend the nation.

The impact of service life on individuals is not likely to change in the foreseeable future, and it is now time to improve and modernise chaplaincy such that it is simple, fair, inclusive and designed to achieve positive wellbe ing outcomes for the ADF’s 60 thousand members – most of whom are not religious.

The obvious approach is one that uses the full range of psychologists, social workers, counsellors and other qualified wellbeing practitioners, working alongside religious chaplains, to provide needs-based pastoral care and wellbeing support to the largest possible proportion of Defence members without the context, connotation or biases of religion.

As we commemorate the veterans of past conflicts, it should never be far from our minds that there are 60 thousand currently serving full-time members who will become the veterans of tomorrow. They deserve and need a contemporary wellbeing model designed for 2022, not 1914.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Department of Defence, Commonwealth of Australia