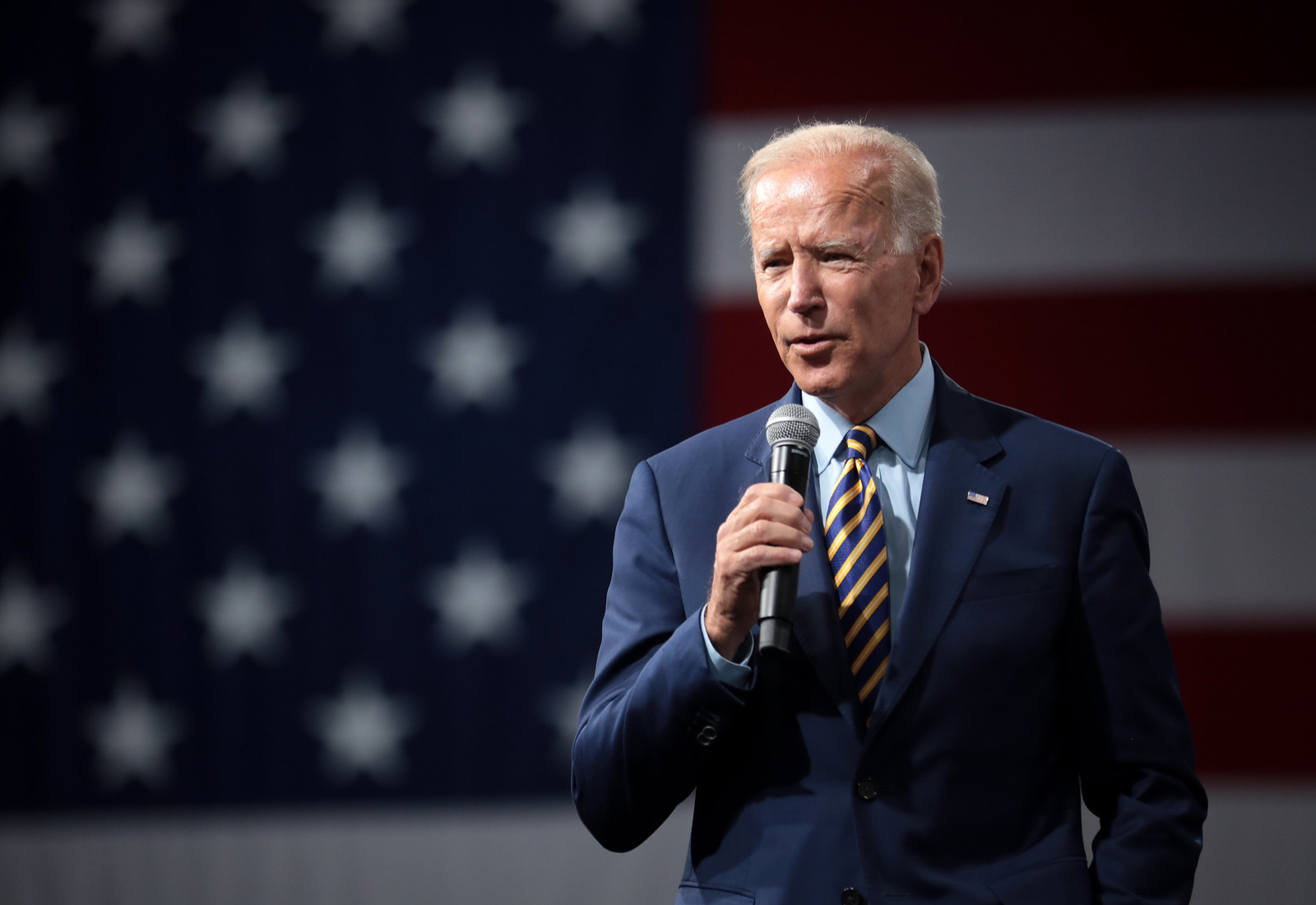

On 9-10 December, the Biden administration held its first Summit for Democracy, a novel initiative seeking to bring government, civil society, and the private sector together to set an agenda for renewing democracy in states worldwide.

It is promoting collective international action in three areas: defending against authoritarianism; addressing and fighting corruption; and promoting respect for human rights.

This speaks to President Biden’s campaign platforms of both restoring and strengthening democracy at home and, in his first foreign policy speech, the need to “earn back” US leadership of the democratic world in meeting 21st-century challenges and the threats posed by the Russian and Chinese governments.

Just 11 months after the 6 January assault on the Capitol, and hot on the heels of the withdrawal from Afghanistan as an abject foreign policy failure, the Biden administration is keen to send a message that the US is returning to its former strength, repudiating the chaotic and transactional approach to foreign policy under his predecessor, Donald Trump.

Held mainly online due to COVID-19, the two-day event had a guest list of participants from 111 states and territories, from Albania to Zambia, with 101 participating (including the US itself, the European Union and United Nations). It was preceded by a range of events on 8 December (‘Day Zero’) and by a diverse mix of democracy-focused events since mid-November.

The good

There is no doubt that there is a pressing need for democracies to focus on reform and multilateralism after a long period of drift.

As the President offered in his opening speech, global democratic regression is “the defining challenge of our time”.

That includes democratic challenges and crisis everywhere from the US itself, to the EU’s relations with Hungary and Poland, and in the world’s largest democracies, Brazil, Indonesia and India – the latter being recategorised this year as not being a true liberal democracy by two international agencies (see here and here).

COVID-19 has exacerbated all of these challenges, with much talk of ‘pandemic backsliding’.

While each democracy has its own problems, all share common challenges like the effects of disinformation, issues of inequality and exclusion, and the challenge of navigating an international environment which has changed drastically since the post-1989 moment in which liberal democracy was presented as the only legitimate political system.

Announcements in President Biden’s summit speech range from a US government Strategy on Countering Corruption, to some $US424 million in funding to support democratic reformers, promote technology that advances democracy, and fair elections. The funding will go towards initiatives including a multilateral International Fund for Public Interest Media, a Fund for Democratic Renewal, and a new Partnership for Democracy program.

The Summit has also ruffled feathers in Russia and China, which suggests a fear that it might actually achieve something concrete. In late November, both governments, who weren’t invited, slammed the Summit in a rare joint op ed as reflecting “a Cold-War mentality”.

China’s state daily The Global Times denounced it as an “anti-China ideological clique”, suggesting the US definition of authoritarianism is outdated and that China has its own system of democracy. On 4 December, the Chinese government even issued a report titled ‘China: Democracy that Works’ – a not-so-subtle dig at the US itself.

The bad

The Summit was a struggle to organise. Not only did COVID-19 ratchet up the difficulty, but I am told by a contact close to the process that preparations were hampered by the gutting of the State Department under the Trump presidency.

Some had dismissed the Summit shortly before it began as “a grab bag of vague ideas”, and reported civil society leaders complaining of being marginalised, with the main emphasis on three-minute speeches by government leaders.

Certainly, the Summit agenda, made available at the eleventh hour, presented a wide-ranging program focused on anti-corruption, disinformation, the digital space and enhancing participation, with leaders taking up most time.

The guest list also raised many eyebrows.

Biden administration officials have publicly insisted that the Summit isn’t about endorsing who is and who isn’t a democracy – hence the name: it isn’t a ‘summit of democracies’. Indeed, of the states invited, only 69 per cent are considered democracies by Freedom House, with the rest deemed partly free (28 per cent) or not free (three per cent).

Authoritarian states not invited included not only China and Russia, but also Cuba, Venezuela, and Afghanistan, and long-term US allies like Egypt and Saudi Arabia. But others, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, were on the list.

These inconsistencies and omissions have been picked over by democracy watchers and the states themselves – democratic backsliding states like Poland and Brazil were included, but others, like Hungary or Sri Lanka, weren’t.

Some states experiencing difficult democratic transitions, including Tunisia and The Gambia, were also not invited.

Others were invited but didn’t attend, like key democracy South Africa, as well as US ally Pakistan, which insisted it doesn’t want to be part of any ‘bloc’. Sources indicate the snub was in response to the exclusion of China.

The ugly

Some see the inclusion of troubled democracies like the Philippines and India as reflecting a China containment club rather than a democracy club, and as being ultimately based more on geopolitical rather than democratic values.

Importantly Taiwan received an invitation (represented not by the Prime Minister but by Digital Minister Audrey Tang), which greatly angered Beijing, but Hong Kong wasn’t invited.

Awkward moments included the organisers allegedly cutting Minister Tang’s video feed when she showed a map displaying Taiwan as separate from China, explained away as a “technical error”.

Many of the videos of leaders’ speeches would act as good sleep aids, being filled with bromides about democracy and working together, but offering little substance. One wag described the event as sounding more like “an international therapy session” – a far cry from the “triumphalist chest-beating” of past meetings of free world leaders.

Rank hypocrisy was also on display, as avowed opponents of democracy issued statements about their commitments to democracy and rights, including Brazil’s President Bolsonaro, an admirer of past dictatorships in Brazil and Chile.

Despite calls to include them, pro-democracy opposition figures don’t seem to have gotten a look in, which raises the issue of giving illiberal governments attending a veneer of legitimacy.

What comes next

The Summit for Democracy is ultimately a foreign policy experiment in rallying democracies and gauging the world’s remaining appetite for USA leadership.

It certainly seems to have achieved its main goal for the Biden administration, which was to put both its authoritarian rivals and allies on notice that the US is back in the frame with a more muscular foreign policy. Yet, for many, including Australia, it passed by with little fanfare.

Biden has vowed 2022 will be a “year of action” culminating in a second Summit expected to build on and reflect on the consultations, coordination, and actions taken after the first Summit.

One analyst has offered that the Biden administration now needs to shift to a broader “strategy of global democracy reinforcement”, including following up on other countries’ commitments.

For many states, that may sound a little too much like a return to the ‘world’s policeman’ role of the post-1989 era when now more than ever it is generally collaboration and support, not oversight, that is welcomed, especially given the USA’s own troubles.

Whether all of this is genuinely – or at least, universally – focused on supporting democrats worldwide is a trickier question. When many governments get a pass despite running roughshod over democracy at home, it suggests much will be overlooked in the aim of strengthening alliances. Perhaps little has been learned from the original Cold War.

Yet, if the Biden administration heeds calls for more civil society and pro-democracy opposition involvement, collaboration and humility, this process could yet bear fruit.

Democrats worldwide can only hope.

This article was originally published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

Photo by Gage Skidmore on Flickr (cc).