After five years of working for the Joint Counter Terrorism Team, where I was consumed by the persistent and genuine threat of Islamic terrorism, there is some irony in the fact the very last investigation I played any role in was the world’s first real example of white nationalist terrorism.

The uncomfortable truth is – and I can only speak for myself – I did not see it coming.

This admission might frustrate some, so it is worth clarifying this blind spot.

The Australian Federal Police, ASIO and state police have been monitoring the rise of white supremacy for years now. The increasing virulence of the rhetoric, the normalisation of racism and the manner in which the internet has polarised, radicalised and collectivised alienated young men wasn’t going unnoticed. However, there remained a crucial difference between the ideology of racism and the ideology of Islamism that meant the nature of the violence they produced was different.

The Christchurch terror attack indicates this distinction is no longer there. So what was this difference?

One of the aspects of Islamic terrorism I found most important for people to understand is the relationship of a Jihadi with death. A catchphrase they often use is: “We want death more than you want to live.” It seems so inane and illogical. But the more I understood the minds of the young men seeking to join this movement, the more I believed it to be true.

The teenager who shot and killed Curtis Cheng outside Parramatta Police station in 2015 was only 15 years old. There is no way he understood the political implications of his actions. Neither do I believe that he genuinely felt there would be any actual policy changes as a result of his actions.

Having immersed myself in the minds of so many young men who planned terrorist acts in Australia, it is clear almost none of them actually expected their actions to result in the shift of Australian foreign policy. Their actions were designed to impress one being – Allah.

These young men didn’t care about winning the war. They believed that dying as a Shahid, or martyr, in an act of Jihad would cleanse them of all their sins and provide them an eternity in the highest level of paradise. Being from often impoverished and outcast lives, the option was often too appealing to turn down.

As an atheist, it was always difficult to empathise with this certainty in their beliefs. They were adamant that God, the creator of everything and most powerful being imaginable, had not only approved their actions but demanded them. They ‘knew’ their violent and painful deaths would validate their faith.

But once you understood they actually believed this as strongly as you believe the sun will rise in the morning, you understand why the Islamic terrorist is so deadly. This was the element I always believed was invariably absent from any white extremist ideology.

The hearts of white supremacy adherents were equally filled with hate; their propensity and glorification of violence no less prevalent. But when the prospect of a large-scale terror attack was raised, I always posed the following questions: in their eyes, was this something they would genuinely die for? Or, at the very least, was this something they were prepared to spend the rest of their lives in prison for?

I believe the Christchurch terrorist had no expectation he would survive his attack. So what made this different?

One possibility is that he was more similar in character to the lone mass shooters, ubiquitous throughout the United States, who develop an infatuation with their ability to carry out a mass casualty event with their firearms and who, eventually, submit to their murderous fantasies.

Indeed, the Christchurch terrorist was gun-obsessed. He resisted pleas from his family to return home primarily because he knew he wouldn’t be allowed to keep his guns.

But there was something more to this man. He didn’t merely attach a cause to his deadly impulses; he was genuinely and sincerely committed to the beliefs he claimed inspired him.

At its core was the ‘Great Replacement’ theory – a theory which suggests an intentional global conspiracy by people of colour to erase the white race through reproduction and immigration.

At its core was the ‘Great Replacement’ theory – a theory which suggests an intentional global conspiracy by people of colour to erase the white race through reproduction and immigration.

The Christchurch terrorist believed in this theory as fact, as you and I would believe the sun will rise in the morning.

In the Great Replacement theory, racism found a dogma, a divine truth. It had, in effect, become a religion. This was the missing step that enabled racism to inspire terrorism.

It is one thing to hate someone for their race or to think them inferior, but this belief would not ordinarily encourage someone to surrender their life. But if you truly believed that your entire race was actually being wiped out, would that not be a cause worth dying for?

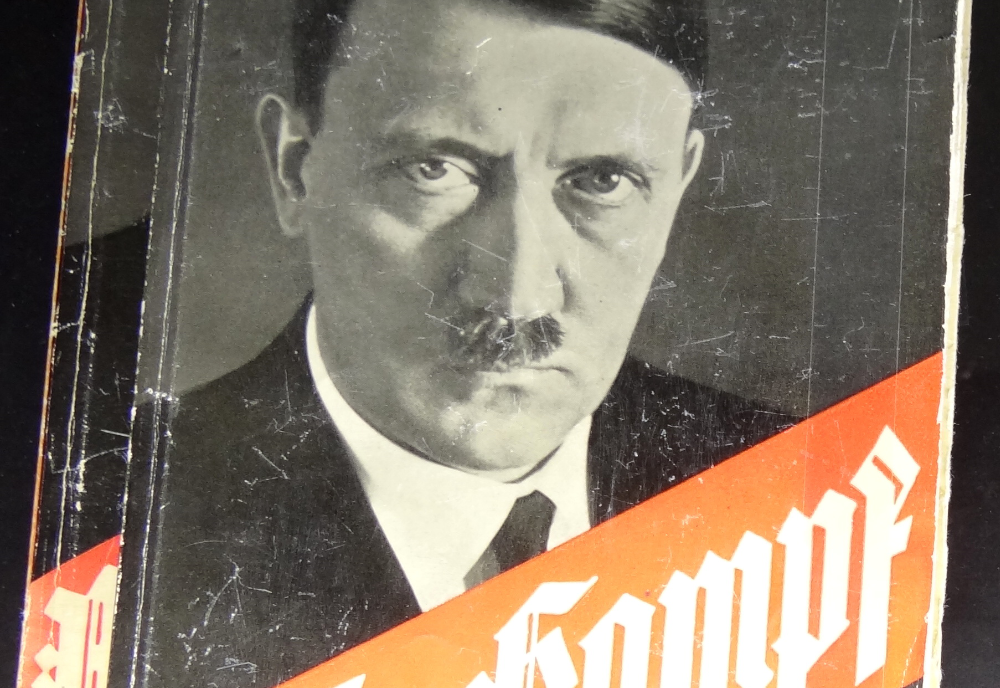

History is stained by beliefs that evolved into inflexible dogmas – and they nearly always turn out deadly. From almost every religion to the ideologies of Nazism and communism – when the individual believes they are aware of an unchangeable dogmatic truth, they become capable of overriding natural morality that exists to prevent acts of cruelty.

This is why the rise of conspiracy theories poses a direct risk to humanity. Just as I urged people to understand that the Islamic extremist genuinely believes God is demanding they carry out their acts, imagine if you actually believed in the tenets of QAnon; if you actually believed children were being abducted, trafficked, tortured and raped on an industrial scale. Would you not be prepared to die to save them?

We know the answer already. In December 2016, an armed gunman entered the restaurant that was the subject of a bizarre QAnon-related theory that children were being kept as sex slaves at the venue. The gunman fired his weapon but was ultimately arrested by police. He stated that he was there to save the children from the sex-trafficking ring.

Now, extreme anti-vaxx conspiracy theories are being built around allegations of mass mind control and enslavement. Again, if you believed this existed with certainty, would you not be prepared to at least risk your life to prevent it?

Any absolutist adherence to dogma is dangerous, and the internet has created echo chambers that reinforce extreme belief systems until they become unshakeable. At this point, an adherent is an instant security risk to all of us. They have almost all become believers in a dystopian religion that is, by its nature, in a constant state of holy war.

The threat of Islamic terrorism has not faded. So long as the dogmatic belief in the religion at its core exists, vulnerable minds risk being drawn to its more violent interpretations.

However the rise of conspiracy theory movements has created a growing list of ideologies that risk turning any vulnerable mind into that of a mass murderer.

The greatest deterrent is critical thinking and the encouragement of doubt.

Healthy scepticism prevents dogmatic belief. Any society that teaches its children that there are divine truths, beyond the rules of mathematics and science, leaves a generation exposed to exploitation.

Photo by Anthony Crider on Flickr (cc)