There is an oft-told joke about someone lost in a rural area who finally encounters a local and requests directions to their destination. The local thinks for a few moments and then replies: “If I were you, I wouldn’t start from here.”

Some of us who care deeply about the state of the world are fearful that the situation in Palestine might have passed the point of no return and that there are no viable, mutually acceptable paths back to a compromise. So much muddy water has passed under the bridge that it is hard to see how any agreement might be reached.

At the root of the problem lie two radically different perceptions of what has occurred over the last 100 years in the so-called Holy Land. Basically, the Zionists see the establishment of the state of Israel as a homecoming; the Palestinians see it as a home invasion. And neither side seems to be capable of seeing the other side’s perspective.

On the one hand, Israel claims a right to exist there. Israelis point to the fact that about 2000 years ago there were two Jewish states in what is now Palestine – Israel and Judea. Moreover, there have been Jews living continuously in Palestine since that time. And, throughout the diaspora, “the Jewish people maintained a strong connection to the land of Israel through religious practices, prayers, and an enduring hope of eventual return”.

So, from the last decade of the nineteenth century, intoxicated by the myths of the ‘Promised Land’ and the ‘Holy City of Jerusalem’, the Zionists arrived in Palestine in their droves. During the British Mandate, the Jewish population of Palestine grew from 83,000 in 1922 to 630,000 in 1947, with settlers attracted by the dream of recreating a Jewish state and driven by the nightmare of the Holocaust.

For many Westerners, even anti-Semites, the idea of a Jewish homeland far away on someone-else’s territory was appealing. Western nations supported the Zionist project for a variety of self-serving reasons: their guilt over their previous antisemitism and especially over not preventing the Holocaust; their relief at being able to transfer the ‘Jewish problem’ away to the Middle East; their need to retain the support of their own substantial Jewish minorities; and their attraction to the prospect of having a strong Western enclave in the predominantly Muslim Middle East.

At first there was a great deal of optimism, even idealism, especially among the pioneers on the kibbutzim. When the state of Israel was proclaimed in 1947, there was an enormous sense of elation that the Jews had finally come home.

There was only one problem. Palestine was not terra nullius. In 1947, the Jewish population of Palestine was still only 32 per cent. In the eyes of the Arab majority of Palestinians, this was not a return but an invasion.

War erupted between the Zionists and the Arabs – which the Zionists won. Many Arab Palestinians became refugees, in Jordon, Lebanon and Syria. The Arab population of Palestine dropped from 1,324,000 to 156,000 in one year, leaving the Zionists pretty much in control, with 80 per cent of the population. There was a ceasefire and Palestine was partitioned into three: Israel itself; the so-called West Bank area; and the Gaza strip. But there was no lasting agreement.

In 1949, the state of Israel received international legitimacy when it was recognised by the United Nations, with the requisite two-thirds majority of the General Assembly voting for Resolution 273, admitting Israel into the family of nations.

But what is crucial is that none of the locals accepted it. Not one of the Middle Eastern and surrounding countries who were then members of the United Nations – Afghanistan, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey and Yemen – voted in favour of recognising Israel. Effectively, the state of Israel was imposed upon the local inhabitants by outside forces. To the Palestinians in particular, and to the Arab world in general, it was a western colonial invasion and occupation, pure and simple.

Believing that the Zionists had illegitimately taken their land, the Palestinian Arabs went on the offensive, and in response the Israelis became more and more belligerent. Some people believe the extremely fierce Israeli reaction to being attacked was partly driven by the shame many Jews felt about the ease with which the Nazis rounded them up during the Holocaust and took them away to the gas chambers without any significant protest or resistance. They were determined this time to put up a real fight.

With the help of their friends in NATO, they soon became the dominant power in the region, even developing and manufacturing their own nuclear arsenal.

Terrorism is the weapon of the powerless. When the Zionists were the underdogs and were fighting to establish an Israeli state in the British Protectorate of Palestine, some of them were happy to use terrorist tactics, both against the British and against the local Arab population. There is even some evidence that they used biological warfare against the latter. But once they had established their dominance, it was the down-trodden and dispossessed Palestinians who were driven in desperation to use terrorism as a strategy and to earn the condemnation of the civilised world.

Capturing the moral high ground has allowed the Israelis to use more and more draconian measures against the much-maligned ‘Palestinian terrorists’, with disproportionate retaliation of biblical proportions. Thus, for every single Israeli killed by Palestinians in the 7 October atrocity, there have now been over 20 Palestinians killed by Israelis, more than half of them women and children. This begins to look more like revenge than self-defence. This disproportionality is not a new phenomenon; it has been the norm since the foundation of Israel in 1948.

Effectively, the state of Israel was imposed upon the local inhabitants by outside forces. To the Palestinians in particular, and to the Arab world in general, it was a western colonial invasion and occupation, pure and simple.

Israel chastises the Palestinians for not acknowledging Israel’s ‘right to exist’. This ‘right’ is based not on universally accepted moral principals but on unique-to-them notions that the Palestinians cannot share – the dream of recreating a state of affairs that existed nearly 2000 years ago (surely the statute of limitations has kicked in) and a set of Jewish religious beliefs that, for the Arabs, are irrelevant.

While there is now no denying that the state of Israel exists and is here to stay, it seems that objectively it was established by colonial conquest, rather than in conjunction with and with the cooperation of the local populace. This has a certain appropriateness to it, since conquest was the means by which the ancient nation was originally established – which the Zionists are now trying to emulate.

Now comes the rub. For peace to occur in Palestine, two monumental ideological reversals will need to occur.

Firstly, the Arabs will need to concede that the state of Israel is now a fait accompli. Whatever the merits or otherwise of its creation, it is now a 76-year-old thriving vibrant nation with a loyal populace committed to defending its territory, and with the support of many powerful friends around the world. There is no conceivable way it could be eliminated, and violent gestures like firing intermittent rockets at Israeli civilian centres and the murderous incursion of 7 October 2023 are useless and counterproductive.

The best way Arabs in the region can ensure the ongoing welfare of the Palestinian populace is to reach a deal with the Israelis that concedes part of Palestine to the homecomers/intruders, in return for support in building their own Palestinian nation as a healthy viable, supportive environment for their people to thrive in.

This is a big ask, and demands a certain maturity, the abandonment of fanaticism and the acceptance of uncomfortable realities – so-called realpolitik.

Secondly, for their part, the Israelis will have to accept that they are not just back where they always belonged, but also where a raft of other people have belonged and have been living for many centuries, and accept that if they are to occupy a substantial proportion of Palestine they will have to make it good in some way to those people.

If you take something that doesn’t belong to you, you are morally obliged to compensate the original possessors in an adequate fashion. The Israelis will have to put aside the notion they are there on a promise from God and accept that they have pushed in where they are not welcome, and there are obligations that go with this.

The Israelis need to make a gargantuan effort to convince the local Arabs that the presence of Israel in their neighbourhood is on balance a good thing and that, with understanding and compromise, it will lead to the welfare, independence and flourishing of all. It may look something like the options set out in Article 28 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – to which Israel is a signatory:

Indigenous peoples have the right to redress, by means that can include restitution or, when this is not possible, just, fair and equitable compensation, for the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used, and which have been confiscated, taken, occupied, used or damaged without their free, prior and informed consent.

Again, this is a big ask. It involves Israel vacating some of the moral high ground and admitting the establishment of Israel was not the lily-white reclaiming of something that was always morally theirs, but was also an act of invasion and colonial settler acquisition based on deeply held but not universally accepted beliefs. It involves admitting that the establishment of the state of Israel took something away from others – others who are due recompense.

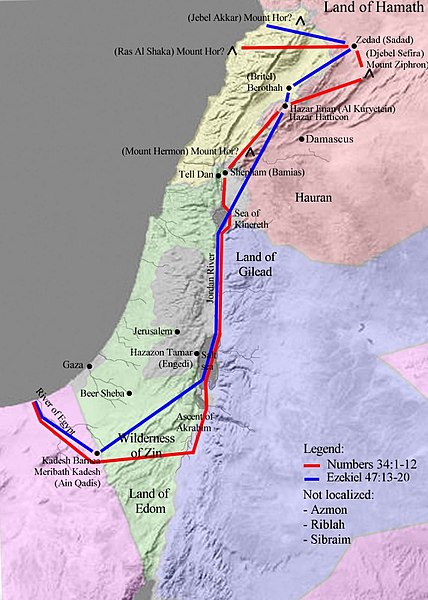

Moreover, there can be no possibility of Palestinians accepting Israel in their bailiwick while so many, especially religious Israelis, including apparently Netanyahu and his cabinet, seem to envision Israel with borders expanded to include as much as possible of ancient Israel, as specified in the Bible (Numbers Chapter 34: 1-12):

The Lord said to Moses, 2 “Command the Israelites and say to them: ‘When you enter Canaan, the land that will be allotted to you as an inheritance is to have these boundaries:

3 “‘Your southern side will include some of the Desert of Zin along the border of Edom. Your southern boundary will start in the east from the southern end of the Dead Sea, 4 cross south of Scorpion Pass, continue on to Zin and go south of Kadesh Barnea. Then it will go to Hazar Addar and over to Azmon, 5 where it will turn, join the Wadi of Egypt and end at the Mediterranean Sea.

6 “‘Your western boundary will be the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. This will be your boundary on the west.

7 “‘For your northern boundary, run a line from the Mediterranean Sea to Mount Hor 8 and from Mount Hor to Lebo Hamath. Then the boundary will go to Zedad, 9 continue to Ziphron and end at Hazar Enan. This will be your boundary on the north.

10 “‘For your eastern boundary, run a line from Hazar Enan to Shepham. 11 The boundary will go down from Shepham to Riblah on the east side of Ain and continue along the slopes east of the Sea of Galilee. 12 Then the boundary will go down along the Jordan and end at the Dead Sea.

“‘This will be your land, with its boundaries on every side.’”

For those whose geographical general knowledge does not extend back to the Middle East in the first millennium BCE, the land that the Bible says God set aside for the Israelites includes not only most of present-day Palestine but also parts of Egypt, Jordan and Syria, and a large chunk of Lebanon (see map). The latter are obviously off limits (for now) but the former is clearly in the sights of many Israelis.

To have any chance of getting the Palestinians on side, the Israelis would have to commit to remaining within something like the 1948 United Nations boundaries. This would include abandoning the 144 illegal Jewish settlements housing over 450,000 Jewish settlers on Palestinian land in the West Bank, or at least integrating them into a Palestinian state jurisdiction – neither of which would be easy, and which the current Israeli leadership seem reluctant to contemplate.

With everyone’s attention focused on Gaza, in the West Bank the illegal Israeli settlers are conducting an escalating campaign of disruption against the local Palestinian population which stops short of killing them but involves a range of non-fatal forms of violence, including beating them up and destroying their property. It also includes attempts to prevent them from engaging in the agriculture (mainly olive plantations) and grazing (goats and sheep) that sustains them. These actions are all clearly designed to force the Palestinians to leave and to seek permanent asylum in neighbouring countries.

While the Palestinians have failed to recognise the unilateral annexation of their land to form Israel, as mandated by the United Nations, it turns out that the Israelis have not recognised the land allocated to the Palestinians in that same agreement.

Given all this intractability on both sides, is peace even a possibility? Or have things passed the point of no return?

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that after a century and a half of hard-line unflinching opposition from both sides, many sacrifices, and a failure to recognise any merit in the other side’s position, opinions and feelings have become so deeply entrenched that change will be impossible. All we can look forward to is more of the same – suffering, death and destruction.

If you want peace in Palestine, don’t start from here. If ever the Holy Land was in need of a game-changing Prophet and Messiah, now is the time!

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Emad El Byed on Unsplash.

Interesting article. What many don’t realise is that 20% of Israelis are Arabs. Of the remaining 80%, only about half are of European origin. Soon after Israel handed Gaza to Palestinian rule in 2005, Gaza was taken over by extremists whose avowed aim was/is the elimination of Israel. Whilst the “Two State Solution” sounds appealing to many it is very difficult to envisage any Palestinian leader/regime embracing the concept and surviving. For the foreseeable future, there appears to be no hope/prospect of a peaceful settlement of the Gaza issue.