In recent decades, governments the world over have increasingly taken action to address the dark history of witch-hunting. In western Europe, memorials to victims have been erected at sites in Bamberg (Germany), Vardø (Norway) and Zugarramurdi (Spain). Many states have also taken to issuing national apologies, with some even granting posthumous pardons.

The witchcraft exoneration movement isn’t simply about addressing past injustices. Violence directed at suspected witches persists across the world today and, alarmingly, seems to be intensifying.

The 2023 Annual Report of the United Nations Human Rights Council asserts that each year, hundreds of thousands of vulnerable people are harmed in locations such as sub-Saharan Africa, India and Papua New Guinea because of belief in witchcraft.

One 2020 UN report states at least 20,000 ‘witches’ were killed across 60 countries between 2009 and 2019. The actual number is likely much higher as incidents are severely under-reported. These sobering statistics indicate a need for urgent government action.

State-issued exoneration for victims of witchcraft persecution isn’t a modern concept. The most notable example was in the aftermath of the Salem witch trials (1692–93), in which at least 25 people (mostly women) were executed, tortured to death, or left to die in jail.

In the decades that followed, the citizens of Salem submitted petitions demanding a reversal of convictions for those found ‘guilty’ of witchcraft, and compensation for survivors. In 1711, Massachusetts Governor Joseph Dudley agreed to these demands.

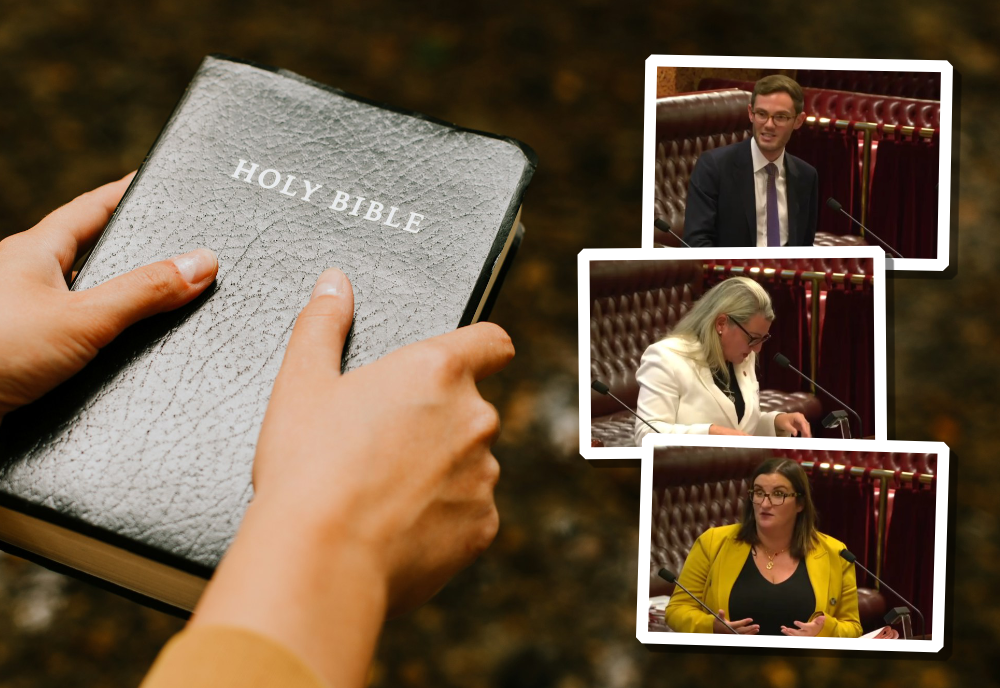

More recently, many states have moved to recognise and make amends for their historical involvement in witch-hunting. On International Women’s Day 2022, Scotland’s former first minister Nicola Sturgeon issued a national apology to people accused of witchcraft between the 16th and 18th centuries.

In 2023, Connecticut lawmakers passed a motion to exonerate the individuals executed by the state for witchcraft during the 17th century. This motion is the result of grassroots campaigning by descendants and groups such as the Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project.

However, as historian Jan Machielsen warns, the exoneration process can also be problematic. For instance, apologies or pardons may ignore the central role of communities in historical witch-hunts.

Most witchcraft accusations emerged from neighbourly disputes and involved active participation by both the community and authorities. Even when European states ceased persecution in the 18th century, community-level violence continued.

Nonetheless, advocates for witchcraft exoneration projects argue that state pardons are more important than ever, not least because they can help address ongoing witchcraft-related violence.

Modern witchcraft persecutions are driven largely by religious fundamentalism and are further exacerbated by factors such as civil conflict, poverty, and resource scarcity. Biblical passages such as Exodus 22:18 are clear on the matter: “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”.

In particular, the growth of Pentecostalism in developing nations has played a central role in fuelling witch-hunts.

Pentecostal evangelising has effectively demonised many cultural traditions – superimposing a strict religious attitude towards magic onto societies that have long accommodated such beliefs. This is evident in the ongoing crusade led by Helen Ukpabio, founder of the notorious Nigerian church Liberty Foundation Gospel Ministries.

Modern witchcraft persecutions are driven largely by religious fundamentalism and are further exacerbated by factors such as civil conflict, poverty, and resource scarcity.

Witchcraft-related violence has also been a growing concern in the United Kingdom, particularly within the African disapora. One of the most shocking cases was the 2010 death of 15-year-old Kristy Bamu in London.

Bamu was tortured by his older sister and her partner for days, as they believed he was a witch. On Christmas Day, Bamu was forced into a bath for an exorcism, where he drowned. In response to such horrific cases, London’s Metropolitan Police launched The Amber Project in 2021 to address increasing incidents of child abuse linked to belief in witchcraft and spirit possession.

Misogyny has also been a prevalent factor in historical witchcraft prosecutions and remains so today. According to the UN, “women who do not fulfil gender stereotypes, such as widows, childless or unmarried women, are at increased risk of accusations of witchcraft and systemic discrimination”.

Witchcraft accusations are often a means to exert control over the bodies of women and girls, while maintaining male-dominated power structures. Accusations also play a role in human trafficking by making it easier to drive victims out of their communities.

Belief in harmful magic and/or witchcraft exists across many societies. India has a long history of witch-hunting and continues to be plagued by this terrible injustice. One victim was Salo Devi, a 58-year-old woman from a small village in the state of Jharkhand. In 2023 she was beaten to death by her neighbours for allegedly bewitching a baby.

Papua New Guinea and sub-Saharan Africa are also hotspots for witchcraft-related violence.

Violence isn’t just used as a punishment against accused witches, but is often part of the remedy. Attempts at counter-witchcraft or exorcisms have been a significant source of harm, particularly for children.

Cultural beliefs surrounding disabilities and misunderstood conditions such as albinism have also been used as justification for beatings, banishment, limb amputation, torture and murder.

So prevalent is such violence that in 2021 the UN Human Rights Council issued a historic special resolution calling for the “elimination of harmful practices related to accusations of witchcraft and ritual attacks”. This resolution urges member states not only to condemn these practices but also to take action to abolish them.

The UN and numerous non-government organisations are implementing programs to educate communities at risk of witchcraft-related violence. Leo Igwe, a Nigerian human rights activist and director of Advocacy for Alleged Witches, has played a central role in increasing public awareness of this violence. More voices like his are needed. At the same time, increased recognition is only the beginning.

The UN has issued numerous denouncements and a few states have introduced anti-witchcraft bills. Additional legal protections, multi-agency task forces and national apologies will help bring more attention to this pressing issue.

Above all, it’s necessary to address the beliefs and motivations that underpin witchcraft accusations. By doing so, we can reverse the alarming rate of witchcraft-related deaths recorded each year.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Phone by Artem Maltsev on Unsplash.