What is post-liberalism? That is no simple question, though the simplest responses are given by those who identify with it as a movement.

Adrian Pabst, author of the most influential book on the subject, proposes it as a way out of the impasse created by the excesses of hyper-capitalism on the Right and identity politics on the Left. He calls for a renewed focus on the collective identities of community, family and location.

British journalist David Goodhart envisages an “embedded individualism”, which acknowledges the messy realities of contemporary life, while insisting on traditional values of interdependence, mutual trust and social duty.

Both writers may be seen as part of a distinctly British mode of centrism, which combines Left-wing commitments to economic justice and workers’ rights with principles of social conservatism. As advocates for consensus politics, they present their views with a reasoned account of the factors contributing to the crisis in liberalism, avoiding shrill statements and overly contentious assertions.

But the movement has less temperate adherents. In the United States, Patrick Deneen has made the title of his book Regime Change a rallying cry, gaining him an enthusiastic audience among some Republicans in Washington.

The “regime” Deneen wants to change is the supposed cultural and institutional dominance of social liberalism – a longstanding shibboleth of the American Right. He talks of a “distinct and pernicious” ruling class arisen from college campus liberals, who have created a new tyranny under which individual rights are the be-all and end-all.

The concept of post-liberalism, then, is ideologically ambiguous. It has the potential to embrace ideas from both Left and Right. Its one common assumption is that traditional liberalism – in its economic and social versions – is in trouble.

Russell Blackford’s How We Became Post-Liberal purports to offer a detached, historical account of why liberalism is in trouble. As its proponents are keen to anchor their principles in deep tradition, the history matters.

There may be no simple answer to the question of what post-liberalism is, but Blackford shows how liberalism may be easier to define, at least in its origins.

His first three chapters chronicle the horrors of religious persecution, from late antiquity through to the early modern period, when liberalism began to mean something more than basic tolerance. Given the strong presence of Christian advocates in the post-liberal movement, it is interesting that Blackford places his emphasis on Christianity as a major player in the history of murderous intolerance.

If liberalism began as a bid to reverse some of the worst tendencies in Christian tradition, what has happened to cause a second U-turn in the movement?

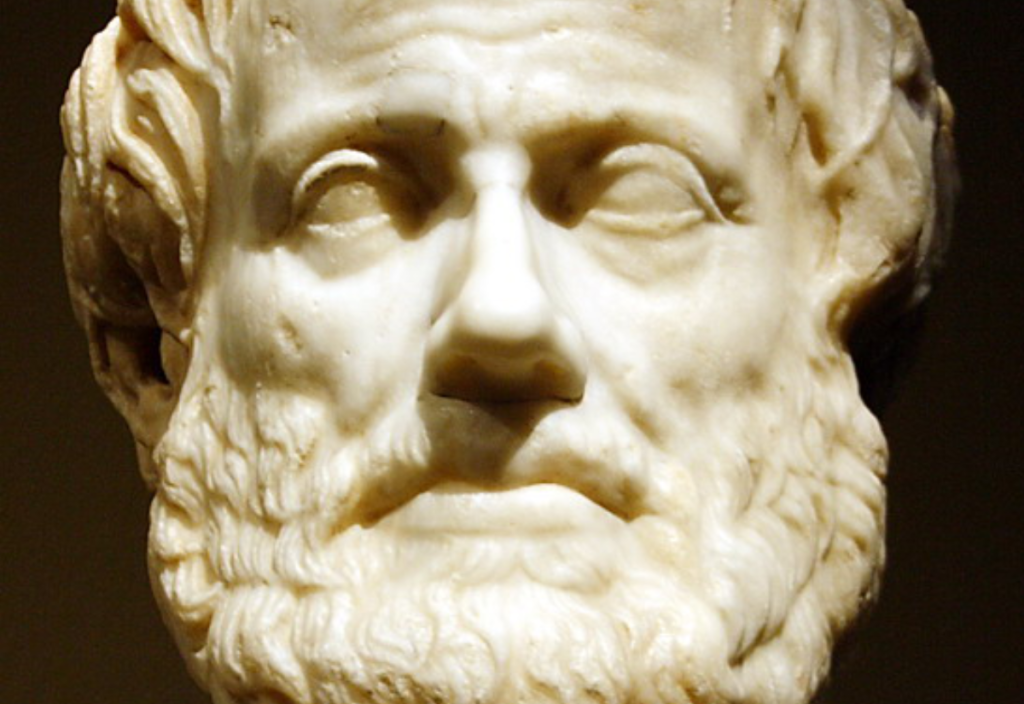

This question underpins much of the argument in Blackford’s book, which pays sustained attention to the fuller realisation of liberalism in the long 19th century, when it became the subject of moral and philosophical treatises.

John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty (1859) argued for the free expression of opinion as a prerequisite to intellectual progress. Perhaps the founding work of modern liberalism, Mill’s essay has been reinvented by current advocates as a primer of post-liberalism.

The expansion of industrial capitalism, population growth and political revolution subjected moral thinking to radically changed conditions. Mill made the case for a shift in values that placed the individual at the centre of the picture. He emphasised the dangers of a new form of tyranny in “the moral coercion of public opinion”.

In the 20th century, the longstanding dynamic of liberalism, which defined the free individual in opposition to church and state, shifted in Europe and America, as political innovators introduced notions of liberalism to government. With the New Deal, Franklin D. Roosevelt succeed in redefining the word ‘liberal’ by associating it with new kinds of government intervention to address social problems.

Free speech became core business in US politics as the Soviet Union moved in the opposite direction. Then came McCarthyism, described by Blackford as “one of the most severe episodes of repression in the universities that the United States experienced in the 20th century”.

The underlying rationales of liberalism, forged through the long 19th century, were threatened with an impossible paradox. What if freedom cannot be preserved without coercive measures? It only takes a significant minority of a democratised population to believe that for the ideals to become untenable.

The paradox played out through the 1960s. Countercultural movements and the rise of feminism introduced more widespread determinations to keep individual freedom paramount. There was never a golden age of liberalism, says Blackford, although for a time we seemed to be on the way.

The radical visions of the 1960s faded into disappointment and disillusionment. Neoliberal policies introduced another ideological twist, with their stringently economic interpretations of individual freedom. A strong element of backlash was in evidence.

Curiously, How We Became Post-Liberal does not really engage with this side of the story. By the time Blackford gets to the mid-20th century, his already sweeping historical canvas has stretched beyond what is really manageable.

Cultural history at this level of generality is something of a Rorschach test. Points are selected from an infinite network of hubs and intersections. A selective design is composed, becoming ever more subject to distortion as it approaches the present.

Blackford’s focus is on the growth of rights movements and identity politics. He spends time examining the controversy over Salman Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses as an Escher-like puzzle, in which contemporary notions of free speech came into conflict with stringent cultural definitions of blasphemy. Claims about rights and their infringement drive in both directions.

The concept of post-liberalism…is ideologically ambiguous. It has the potential to embrace ideas from both Left and Right. Its one common assumption is that traditional liberalism – in its economic and social versions – is in trouble.

And so the atmosphere around liberalism heats up. Melbourne psychologist Nicholas Haslam has identified a trend he calls “concept creep”: an expansion in the use of terms related to the experience of harm – abuse, bullying, trauma, prejudice, vulnerability, being triggered, feeling unsafe.

As Blackford reminds us, harm is a central concern in Mill’s work. It is the philosopher’s guiding principle for where free speech should or should not be sanctioned.

But what happens when a society becomes so obsessed with the anticipation of and redress of harm that the obsession itself becomes a form of tyranny? We are finding out, Blackford suggests, as social justice movements move into a zone where permits for anger and indignation are handed out so keenly they lead to new modes of zealotry and intolerance.

Here lies the central problem with the post-liberal movement, and with the way it is explained in this book. There is too much animus and it is directed selectively. Why focus on social justice movements as the heart of the problem, rather than the culture of extreme individualism generated by neoliberal orthodoxies?

If people on college campuses are becoming prone to zealotry in their campaigns against racism, bullying and harassment, and in their determination to gain recognition for diverse sexualities, what about those in the corporate world who garner obscene levels of personal wealth at the expense of people working for below poverty wages?

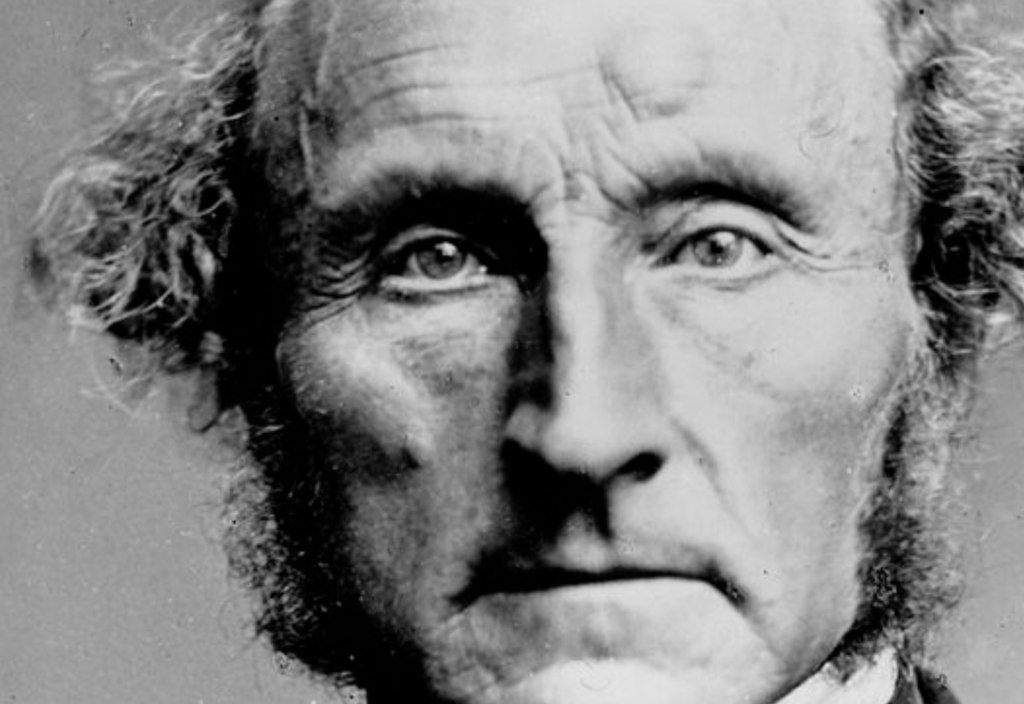

And where are campaigners like Thomas Paine (1737-1809) and William Morris (1834-96) in this history of liberalism?

Paine gets a passing mention as “pamphleteer, free thinker and political radical”. But there is no discussion of his commitment to the principles of social security and a version of basic income as means of redressing extremes of economic inequality.

Morris, who parted company with Mill’s doctrines on free-market capitalism, may be seen as an early example of post-liberalism, but one that moves explicitly towards socialism. Religious persecution may have been a primary cause of intolerance and oppression in the early modern period, but industrial capitalism rapidly took over as the most pervasive form of tyranny in Europe and America.

Here the secular liberalism of US philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002) warrants more than the couple of paragraphs that allude to his work. Rawls’s vision of an economy based on social justice and the greater good has been an influential counterpoint to the orthodoxy of neoliberalism. His ideas, surely, may also be seen as an earlier version of post-liberalism.

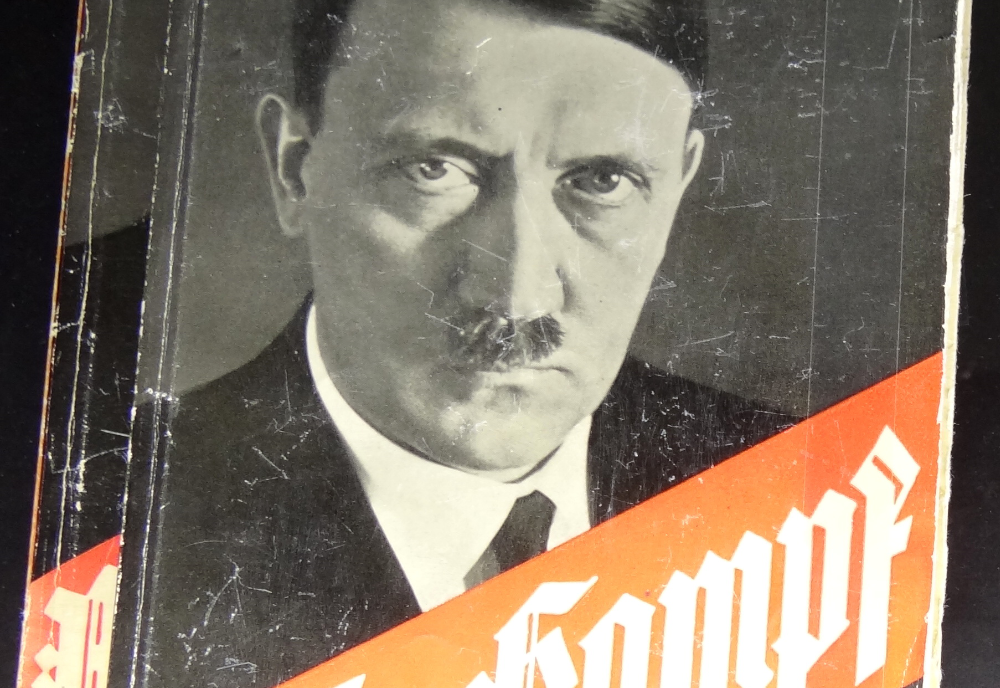

The contemporary post-liberal movement is showing a distinct bias towards targeting identity politics and social justice campaigns. Pabst is one of the few to offer an evenhanded critique on this score. At their worst, the proponents of post-liberalism are starting to sound like Russian propagandist Alexander Dugin, who caricatures Western individualism as infantile indulgence, slurring the word “leeberaleezm” as if it were an obscenity.

Isn’t the problem that we get caught in one vituperative backlash after another? Beware of those who seek to herald new forms of sanity. They may be harbingers of the next wave of tyranny.

Published 22 March 2024.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash.