Some words are like the yo-yo and the hula hoop – they burst into the world as irresistible crazes and vanish almost as quickly when users tire of their novelty.

Perhaps it’s just over-familiarity breeding contempt for shiny new words with short shelf-lives. While these words are easily dismissed as threadbare jargon, they often seem to loiter in the wings and, like the yo-yo and hula hoop, continue to impose their banalities on spoken and written language.

The time has come to challenge these semantic stupidities and to restore some simplicity, elegance and truth to language.

My inspiration is the English essayist William Hazlitt (1778-1830), whose 1821 essay On Familiar Style has been a bright star guiding me for many years. Hazlitt wrote:

A word may be a fine-sounding word, of an unusual length, and very imposing from its learning and novelty, and yet in the connection in which it is introduced, may be quite pointless and irrelevant.

So what has changed in the last 200 years? Not much at all.

Let’s start with three much over-used words that are now all the rage – ‘resilient’, ‘respect’ and ‘iconic’. It seems that no conversation, no TV broadcast, no radio show and no newspaper article is complete these days without each of these words – and sometimes all of them in one article. Their use has become commonplace and idiotic.

Resilience

Every defeated sporting team and athlete, and every individual and community facing natural disaster, is declared ‘resilient’ by journalists and observers who apparently feel an urge to make losers feel better in their suffering. Too often they are just wrong.

Resilience is not automatic and universal. Individuals and groups sometimes just give up, depressed and defeated, and never bounce back to happiness and prosperity. Morale-boosting declarations of resilience might be helpful in some circumstances, but they can be empty, misleading and inaccurate.

‘Resilience’ has outstayed its usefulness and should be expunged from contemporary reports on disasters and sporting contests.

Respect

Nowadays you cannot enter any shop, office, bank, hospital or private or government agency without confronting notices insisting that you treat every worker with ‘respect’. You must not complain, express frustration or irritation with even the most mulish, moronic, incompetent, unhelpful and lazy worker.

What’s more, ‘respect’ – and its derivatives like ‘respectfulness’ – is demanded of all participants in debates on contentious public issues. What absolute nonsense.

‘Respect’ reflects the triumph of political correctness – the code of self-imposed censorship that has bowdlerised much frank and vigorous debate in the English-speaking democracies.

Genuine respect has to be mutual and earned. It cannot be imposed by notices on doors and walls, or by the moderators of TV discussion shows. You give what you get and you cannot reasonably expect individuals to extend respect, patience and politeness to rude, unhelpful or incompetent people who are supposedly employed to help them.

Nor should individuals be expected to remain passively respectful in public to people whose views and expressions are offensive to them. Again, in debate, you get what you give and you give what you get. We could do with less respect and more frankness.

Iconic

Then there is ‘iconic’, the adjective derived from the noun ‘icon’, a devotional or holy painting or statue. This word is used now to invest just about any person or object with silent reverence once granted only to saintly and holy images. Those who casually attach the word ‘iconic’ to anything that takes their fancy might ask themselves this question: what devotional or holy properties are possessed by, say, an automobile or a dishwasher described as ‘iconic’ by some sleazy salesman? The question is too stupid to be taken seriously – as are people who insert ‘iconic’ into much of the nonsense they feel moved to write or speak.

Two other words, once entirely understandable, have now been transformed by some strange linguistic alchemy into signals of virtue and right thinking in every political debate that attracts public attention. At every discussion touching gender, immigration, sexuality and race, the words ‘inclusiveness’ and ‘diversity’ are sooner or later – mostly sooner – wheeled out by pious souls as knockdown reasons for supporting their views and to rebut what they see as the racist, fascist character of every opposing view. ‘Inclusiveness’ and ‘diversity’ are self-evidently good words; exclusivity and uniformity are assumed to be bad, negative and intolerant words, and evidence of bigoted, selfish, uneducated minds. This seems to me absurd.

Why should inclusiveness and diversity be imposed on people who don’t want them? Why should such people be viewed as negative and intolerant?

Consider a private group, club or congregation of believers who meet privately to debate, pray, and to study and practise according to beliefs which the wider community opposes or considers eccentric. Should they, in the name of inclusiveness and diversity, be criticised if they resist the admission of hostile people wanting to overthrow their harmless practices and beliefs? Should demands for inclusiveness and diversity automatically trump the conscientiously-held eccentric, even controversial, beliefs and practices of a group that wants to retain its privacy and exclusivity?

This argument of course cuts both ways. Groups seeking access to exclusive organisations in order to challenge their uniformity and to force diversity on them would, to be consistent, have to allow opposition groups access to their gatherings for the same reason. Would they be willing then to proselytise for diversity? I doubt it.

These questions often arise in matters touching sexual and religious organisations. So should gay-rights bodies be pilloried if they refuse to admit advocates opposed, say, to marriage equality? And should marriage equality groups be forced to take opponents of marriage equality (ie opponents of same-sex marriage) into their councils. I think not.

You can’t force inclusivity or diversity on people who want to defend their traditions and beliefs in private without harming others. To do so would be to undermine the very idea of diversity. There is abundant space in the marketplace of ideas for these debates to take place if the parties want to have them.

Why should inclusiveness and diversity be imposed on people who don’t want them? Why should such people be viewed as negative and intolerant?

I am no expert on the use and misuse of words, but I have been playing with words for a long time as a newspaper hack working under tight deadlines to deliver something publishable to a news desk often half a world away. The lure of jargon words is that they save time and thought and space – they can endow a narrative or analysis with at least the appearance of some insight. Words like ‘escalation’ and ‘de-escalation’, for example, lent a certain, if spurious, weight to articles about strategic issues many years ago. Now ‘escalation’ and ‘de-escalation’ seem, happily, to have gone the way of all threadbare words.

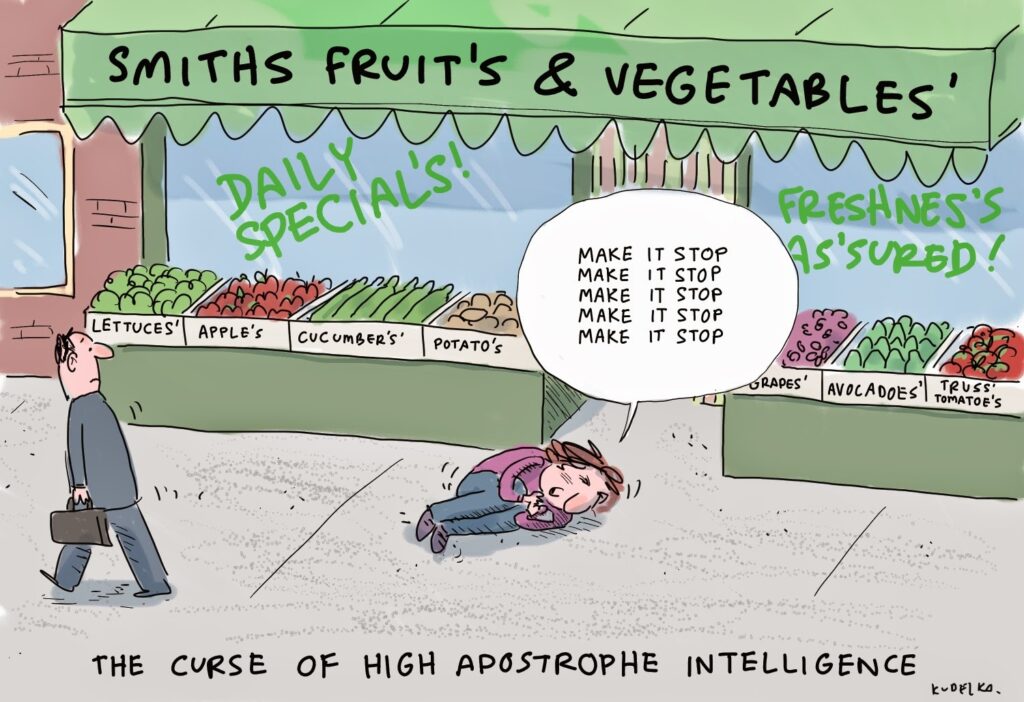

The downside – another example – is that the writer risks ridicule for doing violence to the language. Consider these two currently entrenched absurdities: “ground to a halt” and “off the back of”’. Workers “stop work’’ or “strike”? Factories and transport systems shut down, stop or close. Nothing grinds. It is a bullshit cliché. And when A “comes off the back of’’ B, A really just follows or comes after B. The back reference is meaningless and irrelevant, another utterly threadbare cliché.

In recent times the federal Treasurer, Jim Chalmers, has taken to putting on his compassionate TV face and saying that he knows many Australians are “doing it tough”. This is a vile abuse of language. You are “doing it hard” when you are working long hours for low pay or when you are trying to dig a hole through hard dry ground. “Doing it tough” does not even approach describing what millions of Australians are facing in the present economic climate. These people are terrified as they face homelessness, unemployment, poverty, hunger, untreated illness, poorly fed and poorly-educated children, and a slew of other perils that destroy human security and happiness including diminished life expectancy. They are not merely “doing it tough”. They are expendable goats being sacrificed on the altar of rational economic management. “Doing it tough” is an offensive phrase designed to conceal and to minimise this suffering, and we ought to be saying so.

It is not perhaps surprising that the word ‘passionate’ seems to have been co-opted by advertising copywriters. Sex and passion are, after all, sure to attract attention to a product. “We’re passionate about our washing machines” (or refrigerators or any other household goods) and “we won’t be beaten for price”, shout TV hucksters when they intrude into the homes of TV viewers. It is a curious development in the decline of language. I can understand people being passionate about personal relationships and religious, political and other commitments, and I can understand passionate attachment to the work of writers, composers and other artists. But refrigerators? Stove tops? Barbecues? It is ridiculous to claim these items as sources of joy, tears, sexual arousal or passion. But advertising copywriters are without conscience or shame, and the ludicrous nonsense continues.

These few examples hardly exhaust the violence done to language in the service of commerce. But even worse is done in the service of art by critics who see their role as inducing sensitive souls to flock to every work shown in theatres and cinemas. They are expected to be seduced by works that are ‘dystopian’, ‘coming-of-age’, ‘elegiac’, ‘retro’, ‘high camp’, ‘tragic’, or some other contrived term designed to put bums on seats. I think it is time to consign these words to the garbage bin of mindless language.

After all, ‘dystopian’ simply means dark and nightmarish; ‘coming of age’ generally denotes randy teenagers; ‘elegiac’ generally means just mournful; ‘retro’ means backward looking in style and symbolism; ‘high camp’ generally denotes exaggerated homosexual sensibilities. So let’s say so plainly and unambiguously. We don’t need the pretentious (or is it portentous?) flourishes that do nothing to enhance the critic’s work.

There is much more to say about this issue. I have missed or ignored many words that deserve the literary equivalent of capital punishment. So read this as an appeal for what Hazlitt called “a familiar style”. Hazlitt, a simple vigorous man, summed it all up much better than I can:

A truly natural or familiar style can never be quaint or vulgar, for this reason, that it is of universal force and applicability, and that quaintness and vulgarity arise out of the immediate connection of certain words with coarse and disagreeable, or with confined ideas.

We could do far worse than heed Hazlitt’s advice.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Siora Photography on Unsplash.