Story was once a tool for understanding the world and for improving it. The hero or heroine always defeated the monsters.

Today, story has become a weapon for undermining the world’s values and for creating and nourishing real monsters who would destroy that world.

By a story, of course, we mean an account of a series of connected events, either true or imaginary. “The King died; then the Queen died,” is not a story because it describes two unrelated events. “The King died, and then the Queen died of grief,” is a story, albeit short, because it causally relates the second event to the first.

The ability to tell and absorb stories has always been an important distinguishing feature of the human species, and one of the traits that distinguishes us from other species. The human ability to tell and absorb stories has materially helped us evolve the complex civilisation that we inhabit today.

In the past, stories have been a main method for remembering vast amounts of important information and detail, since they have linked together large amounts of knowledge in meaningful, plausible and emotionally satisfying ways. For example, the songlines of Indigenous Australians consist of stories that contain and preserve much important information about the country and its history, its plants and its creatures, its seasons and the annual motions of the heavens.

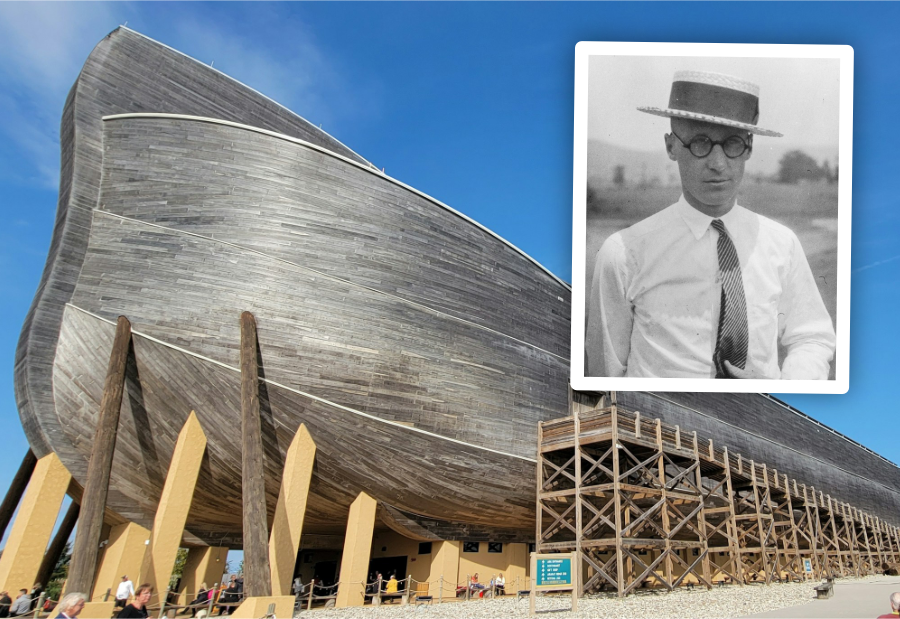

The world’s most successful religions are based on stories. For example, Christianity is based on the story of how a Jewish deity, who was his own father, allowed himself be painfully killed – although he didn’t really die – in order to give himself permission not to send us to a place of eternal torture that he had created for us. And now, if we symbolically eat his flesh and drink his blood, he will cleanse us of an evil force that is present in all mankind, because a rib-woman and a mud-man were convinced by a talking snake to eat from a magical tree.

Islam is based on the story that, after creating the universe for humans, God left us more or less to our own devices for many millennia, but in the year 0 (or 1610 CE in the other mob’s system) decided He needed to communicate His instructions and His philosophy of life to the human species. So He determined that the most effective way of doing this would be to send a messenger to appear in a secluded cave in a remote desert to a little-known illiterate member of one of the most aggressive and misogynist tribes on earth, and to instruct this guy to get his mob together and mobilise them to convey God’s messages to the rest of humanity, if necessary, by the sword.

Legal proceedings often come down to determining which of two contradictory stories is the more plausible. Did Chris Dawson’s wife Lynette, in a moment of distraction, suddenly run off by herself and completely disappear from sight, leaving her beloved children and all her possessions behind, and become so disassociated from her former life that she never again tried to communicate with them or with any of her other close friends and relations? Or did Dawson become infatuated with their young baby-sitter and murder his wife and successfully dispose of her body, so he could marry his teenage lover.

The power of story-telling has always been essential to our social fabric. The story of the hero or heroine who triumphs over adversity and saves his or her people is the central narrative of human cultures around the world.

Stories of heroic acts of nation-building underlie the raison d’etre of every country on earth. Where two such stories contradict one another, we can get violent clashes, as is the case in Ukraine at the moment.

In Palestine today, two stories clash starkly. The Israeli story tells of an ancient and often persecuted people who have returned, after a diaspora of nearly two millennia, to claim the territory they once possessed and which they originally took by force nearly three thousand years ago after God chose them and promised them the land.

Opposing this is the Palestinian Arab story in which the Palestinians have resided there for many centuries, surviving successive occupation by Byzantines, Crusaders and Ottoman Turks – and even briefly hosting God’s one-and-only prophet, who called by Jerusalem on a magical flying horse on his way up to Heaven – only to have a group of mainly European interlopers descend on them, claiming they had a God-given right to return and take over the joint, despite the statute of limitations.

The power of story-telling has always been essential to our social fabric. The story of the hero or heroine who triumphs over adversity and saves his or her people is the central narrative of human cultures around the world.

Australia is currently grappling with the uncomfortable fact that the terra nullius story that the 19th-century European settlers told themselves was patently false, and is now trying to come to terms with an emerging story which involves an indigenous people who have successfully looked after this continent for tens of thousands of years and who now want a Voice.

Our central stories are so important that rulers often take extreme measures to protect them. In Europe, the Catholic Church, for hundreds of years, took stringent steps to protect the integrity of its central narrative, and anyone attempting to tell a different story was burnt at the stake.

More recently, totalitarian regimes have gone to extraordinary lengths to control their self-justifying narratives through their rampant propaganda and intrusive secret police.

In Australia, successive governments have committed millions and millions of dollars to expenditure aimed at propping up our dubious ANZAC story and our digger myth.

As the ancient Greek philosopher Plato is often quoted as saying, “Those who tell the stories rule the world”.

In the past, we recognised the two distinct categories of knowledge dissemination: stories and storytelling on the one hand; and research and information collation on the other. One set of shelves in the library or bookstore was labelled ‘fiction’ for unequivocally ‘made-up’ stories. The other set of shelves was labelled ‘non-fiction’ for factual reports not ‘made up’ but are accounts and arguments which claim to be evidence-based and attempt to set out the truth of the matter. And we all knew which was which.

Of course, this was to some extent an artificial distinction. Verisimilitude, being ‘true to life’, is one of the qualities we value in even the most imaginative stories. Even highly speculative fiction – sci-fi and fantasy – needs to be at least ‘psychologically true’ to command our attention.

On the other hand, some avowedly fictional books – for example, autobiographical novels – might have a great deal of actual truth in them, disguised as fiction. And, of course, conversely, some purportedly non-fiction books patently have a tenuous relationship to the truth.

This distinction between fiction and non-fiction is clearly not a value judgement – ‘true stories useful’ and ‘fictional stories frivolous’ – since many of our most influential books have been works of fiction.

Fictions such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, and 1984 by George Orwell have all had a profound effect on the world. They stand with seminal non-fiction works such The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft, and On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin as among the most influential books in our history.

But the question now is: has the human propensity for telling and sharing stories gone too far and become counter-productive? Has the storytelling ability that enabled us to dominate the world now become the Achilles heel that will lead to our destruction? Is our limited ability to distinguish between true story and fiction becoming our downfall?

Postmodernism has proclaimed the demise of the ‘grand narratives’ that sustained societies in the past. But, unfortunately, these have been replaced by a countless myriad of questionable tales and stories of dubious veracity that are circulating willy-nilly on social media and are virtually impossible to monitor or regulate.

In the 21st century, stories are rapidly again becoming our main vehicle for sharing information. The problem is that not only do stories seem superficially more compelling in their impact on the listener than tables of data but their veracity is also harder to check and to confirm.

Moreover, the ubiquity and dominance of social media in the last 20 years has made the mass circulation of innumerable stories by anybody and his aunt as easy as pressing an ‘enter’ key.

Today, story is rampant everywhere and seems to be supplanting straightforward information as our major source of knowledge.

Go to a company website and the opening gambit will be ‘Our Story’. Commercial merchandise used to be promoted in the media by listing the product’s positive features and advantages. Nowadays advertisements will tell you a heart-rending story about a lovely couple who used the product to save their cute child – or the stupid nong who didn’t, with disastrous consequences.

Investment decisions are made not on the basis of audited balance sheets but on the basis of the compelling story a corporation puts out about its future prospects.

Science has caught the story bug. Scientific knowledge these days is being presented as narrative – for example, ‘The Story of Evolution’, ‘The Story of the Big Bang’, or, as currently seen on the ABC TV, Australia’s Wild Odyssey.

Even the once-trustworthy ABC TV news has been sucked in. When an issue is raised in the news, instead of presenting information and analysis by experts, the ABC features anecdotes about the way some random citizen has coped (or not) with the issue in question. The important axiom, ‘Anecdotes are not evidence’, seems to have been forgotten.

…the question now is: has the human propensity for telling and sharing stories gone too far and become counter-productive?

These days, instead of asking a new acquaintance who they are, we ask them “What’s your story?” One recent writer has called this phenomenon “the storification of reality”.

There are consequences of this over-reliance on story. Fanciful stories of a ‘stolen election’ led directly to the mob storming of the Capitol in Washington DC.

Even though the claim made last century that the standard measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine caused autism in children was thoroughly debunked and shown to have been concocted by a guy who wanted to promote his own alternative vaccine, this false story still attracts followers here in Australia.

Although vaccine rates across Australia are some of the world’s highest, they are significantly lower in arty-farty anti-establishment communities, such as Byron Bay in New South Wales and Castlemaine in Victoria.

This existing anti-vax movement fed into and helped to amplify the anti-vaccination movement during the COVID-19 pandemic of recent years, leading to some violent demonstrations in Victoria.

This, in turn, was fertile ground for the notorious QAnon phenomenon, which has increased its foothold in Australia, especially amongst the so-called ‘wellness’ community. A 2020 paper released by the British-based thinktank the Institute for Strategic Dialogue revealed that, after the US, Britain and Canada, Australia is the fourth-largest producer of QAnon content in the world. This is a sobering statistic.

The fact that we valorise stories so readily is partly genetic. Our brains are programmed to process stories almost as though they were reality.

Research has shown that reading a story about an action triggers the same areas of the brain as actually performing that action does. Also, this same response occurs in the brains of all the members of an audience listening to that story being read to them.

In an even more remarkable recent study, subjects all listened to the same story in separate locations on the planet on many different days. The study found that all these diverse people underwent the same variations in heart rate as they listened to the story – that is, there was a coordination of the physiology of the body in response to the narrative. This shows the power of narrative and story to affect not just our minds but our bodies.

It is not just their visceral impact that makes the spread of conspiratorial narratives appealing to so many people. There is also a powerful emotional component to belief in conspiracy stories, which helps explain why they can be so difficult to challenge. Feeling part of an exclusive community of fellow believers helps to satisfy people’s need to feel part of a special elite who is ‘in the know’.

Exposing and discrediting conspiracy stories is not straightforward as they are especially resistant to critique. Any story posing as factual without any evidence to support it should be easy to dismiss. But because conspiracies are, by definition, concealed, there being no evidence for the existence of a particular conspiracy is taken as proof it exists. And this shows, therefore, just how clever the conspirators have been in concealing their machinations. A lack of evidence, instead of counting against a conspiracy theory, can tend to reinforce it.

A further problem for us is that, as human beings, we are not very good at spotting the lies told by accomplished liars. Although many people claim to have inbuilt lie detectors in their intellectual armoury, repeated experiments have shown that the performance of humans, even those who claim to be good at it, in picking which persons are lying and which are telling the truth is no better than chance.

‘Intellectual humility’ – constantly keeping in mind the possibility that one might be wrong – is an important trait in scientists, and in thinkers in general. Recent research has shown that believers in conspiracy stories often have an inflated sense of their own intellectual competence, which, taken with their greater-than-average tendency to see patterns and connections where none exist, creates a milieu where conspiracy stories can thrive.

Stories and storytelling are our life blood. We need them to be human. The real and pressing danger to human civilisation is not stories in themselves, or even stories that are unapologetically untrue, but stories that claim to be true when they are not. Because of the power stories have over us, we need to be eternally vigilant against such spurious stories.

It is also worth pointing out that even totally accurate stories are, in one sense, ‘untrue’ in that they are condensations and abstractions of the facts. Even a true story can never be the whole truth about any situation or event.

The bottom line is: we must go beyond relying solely on stories as the source of our understanding and of our world view. We must heed that old saying, ‘Anecdotes are not evidence’, and go in search of the evidence.

We must treat each story we hear or read cum grano salis, especially stories which reinforce our own preconceptions, beliefs or prejudices, as they are more likely to con us. Don’t take compelling stories at face value. Always seek to unearth the facts of the matter, drill down into the details, question the assumptions, put the assertions to the test of the research. Make the story the beginning of your quest for truth, not the conclusion.

Perhaps ‘critical narratology’ should become a core subject in the school curriculum.

Fortunately, the world wide web, which has been the unwitting accomplice in the dissemination of narrative nonsense, also contains the seeds of its destruction. It gives us the tools to check the provenance of a story, to search for countervailing evidence, to explore other views – in short, to weigh up the evidence.

In this regard, it is worth giving a plug for snopes.com, which correctly describes itself as “the definitive Internet reference source for researching urban legends, folklore, myths, rumours, and misinformation”.

Don’t lose your love and enjoyment of story; treat it as a potential friend. But don’t give stories more credence than they deserve. And certainly don’t weaponise them or use them to mislead others.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Mike Erskine on Unsplash.