Our voting choices are only authentic if our decisions are informed by truthful information. That condition is now increasingly elusive.

In Australia, over two-thirds of adult news consumers report having seen media items they considered to be deceptive. This includes misleading commentary, doctored photographs and serious factual errors.

Political disinformation damages democracies. First, it manipulates voter preferences and distorts election results. This could be seen, for example, in the 2016 US presidential election and the Brexit referendum that same year.

It also polarises the electorate, damages trust in government and democratic institutions, and triggers civic withdrawal.

A further harm is that it raises the costs of voting. Electoral legitimacy requires that the costs of participation are not too high; false claims cause information costs to escalate because much more work is required to sift the facts from the false information.

A new and corrosive form of disinformation is political conspiracies of the “stolen elections” variety. This type delegitimises election processes, generates doubt about the authenticity of the declared result and undermines the authority of the electoral victor, who may subsequently experience problems in governing.

It can even lead to serious social conflict such as the storming of the US Capitol in January 2021.

A global problem

Election conspiracies also happen in Australia. During the 2022 federal election, the Australian Electoral Commission sought to counter a “dangerous” disinformation campaign waged by minor party candidates baselessly predicting a high degree of electoral fraud and interference with the results.

Examples of such baseless claims included: the AEC is “aligned to the Liberal Party”; Australians who are not vaccinated will not be able to vote; blank ballots and “donkey votes” are counted for the incumbent.

The media landscape and its political economy have eroded both the media’s willingness to supply “truth” in political discourse, and the consumer’s demand for it.

Social media have decreased barriers to entry into the information marketplace. Meanwhile, many consumers seek out information that confirms their existing prejudices. In some countries there is now a lucrative market in the production of “fake news” solely to meet consumer demand.

To make matters worse, the ability of consumers to distinguish between authentic and fake news is much lower than they realise.

So, there are perverse – and arguably ineradicable – incentives within the information market to produce disinformation. The market is not just failing; it is the source of the problem.

This means disinformation has become what is known as a “collective action problem”. This happens when the actions of market actors create social costs that require state action to clean up or prevent.

Notably, 84 per cent of Australians agree on this need and would like to see truth in political advertising laws in place.

But this is easier said than done. What if, for example, votes and entire elections really are being stolen? We must ensure solutions do not do more harm than good, inadvertently obstructing the free flow of reliable information that is the lifeblood of any democracy.

In our recent book, Max Douglass, Ravi Baltutis and I explore how this might be achieved federally. We propose a cautious approach that draws lessons from laws that have operated successfully in South Australia since 1985.

Seven ideas for reform:

- To avoid chilling political speech – and thereby violating the implied freedom of political communication under the Australian Constitution – truth in political advertising laws will only target identifiable political actors who are authors or authorisers of the material in question. Publishers are therefore exempt, for now at least.

- Only false statements of fact (rather than opinion) will be subject to the law, as per the provisions under section 113 in South Australia.

- To deter vexatious and trivial complaints, the legislation should be limited to false statements that could affect an election outcome to a “material extent”.

- Laws should cover the entire period between elections, to take in preference allocations.

- Penalties – which apply only to those who refuse to take down offending material – should be high enough to deter wrongdoing. However, because some political actors will cynically treat the penalty as a routine expense to gain a political advantage, we propose an additional penalty that bars the candidate from standing for one election cycle, as is the case under UK law. This is hardly controversial since section 386 of Australia’s Electoral Act 1918 already disqualifies those who have committed electoral offences such as bribery, undue influence, and interference with political liberty.

- Regulators should be properly resourced.

- Electoral candidates could be asked to sign a declaration that they have read and understood what the legislation requires of them.

All of this is feasible, as the South Australian example has shown.

This article was originally published in The Conversation. It is republished under Creative Commons.

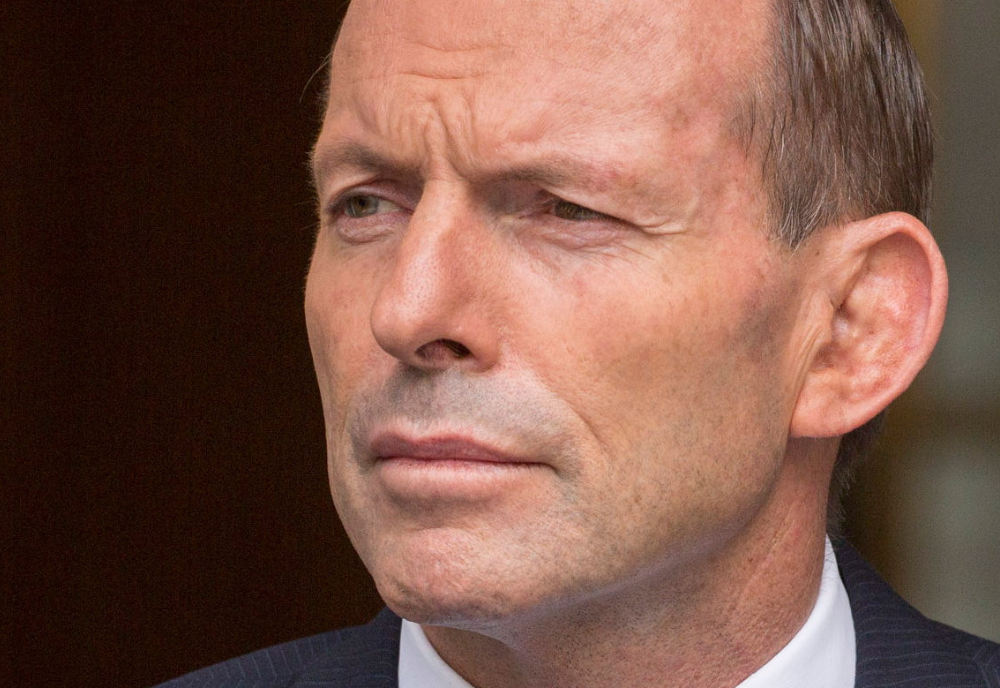

Photo: Screengrab of Liberal Party of Australia ad.