The overwhelming majority of Australians who have served in war zones have been volunteers. However, during the Vietnam war, 63,735 males were conscripted. Of these, 15,381 served in Vietnam; 45,619 regular defence personnel also served in Vietnam, of which 319 died. Of the conscripts who served in Vietnam, 202 died. This means that conscripts were nearly twice as likely to die as regular service personnel.

The president of the local branch of the Vietnam Veterans Association said: “That conscripts are overly represented in the death rate is [a] direct result of the fact that conscripts were more likely to be placed in combat roles than the regular service personnel.” He added that: “Today, there is no overt difference in the members of the Vietnam Veterans Association of Australia with respect to regular or conscripted status.” Nevertheless, you cannot escape the fact that it’s one thing to go to war willingly and entirely another thing to be compelled to do so.

At the time I was posted to PNG, it was under Australian administration. All non-indigenous individuals, including members of the Australian Defence Force, were referred to as Europeans. This was strange, as I had seen Europeans as foreigners.

In 1884, the southern part of PNG became a protectorate of Britain and was named British New Guinea. The northern part was annexed by Germany and became German New Guinea. The name Guinea is derived from the West African country of that name. In 1906, Britain transferred their part to Australia and renamed it the Territory of Papua.

Australian military forces occupied German New Guinea during the First World War, and in 1921 the League of Nations granted Australia the authority to run the region under the name of the Territory of New Guinea, which was governed separately from the Territory of Papua. Australia began the joint administration of both territories under the name of the Territory of Papua and New Guinea in 1949.

The first Australian soldiers sent to PNG to fight the Japanese were members of the militia, which was originally a part-time home defence force. These were reinforced with the return of the Second AIF (Australian Imperial Force) from North Africa. The soldiers of the Second AIF were some of the very few among the allies who served in both theatres of war in fighting the Germans, the Italians, the Vichy French and the Japanese.

The road to independence for PNG began in 1951 when a 28-member legislative Council was established by Australia. However, it was not until 1961 that elections included the indigenous population having the right to vote. In 1971 the ‘Territory’ part of the name was dropped and it became Papua New Guinea. Then on 16 September 1975, full independence was obtained and 800 Signals Squadron ceased to exist.

The 800 Signals Squadron was located at Murray Barracks in Port Moresby. I served alongside some local soldiers. They were tough, funny and reliable. PNG is a diverse place. Some of the local soldiers came from Bougainville and a nearby small island called Buka. These soldiers never used the name Bougainville, which is derived from an 18th century French explorer of that name. For them, it was Big Buka and Little Buka.

I served alongside some local soldiers. They were tough, funny and reliable.

Two types of uniforms were issued. There were the jungle greens that were used prior to the camouflage ones that are worn today. And there was a short-sleeved shirt and those rather daggy long shorts that you see in documentaries about the Second World War. The colour was referred to as juniper. However, it was more aqua than green. This uniform also involved wearing juniper coloured long socks and black shoes. On ceremonial occasions the shoes would be replaced with boots. A long piece of black material called a puttee would be wound around the ankles.

We were also issued with patrol boots made of canvas and rubber. The theory was that although the water would readily invade the boots, the canvas would allow them to dry out more easily than leather boots. In reality, the rubber retained the water and the canvas never dried out.

Each local tribe we encountered told us that the tribes ahead of us, or those on the other side of the valley, were bad people who would eat us given half a chance. Many of us lost a few kilos during the patrol but everyone managed to arrive at our destination with all our parts intact.

That destination consisted of a small village surrounding an airstrip cut into the side of a mountain. The strip was extremely short and sloped down and dropped off to a river far below. The remains of a crashed plane lay at one end of the strip. We were not filled with confidence.

The Caribou plane which returned us to Port Moresby needed the whole strip to get off the ground. In PNG, you don’t fly over mountains, you fly around mountains – which makes for an up-close scenic flight.

A fellow soldier was posted to serve a stint at Vanimo. Some months after he departed, we were told that he had ‘died suddenly’. Of course, this was code for suicide. There was also speculation that his sexual orientation may have had something to do with his death. To a young soldier like me, he appeared to be a very self-contained and self-confident individual. We don’t always know what lies just below the surface.

The Papuan Province of Indonesia, which in my time was known as West Irian, along with the province of West Papua, forms the western half of the island that contains PNG. It was once controlled by the Dutch. Wikipedia states that: “From 1950 onwards, the Dutch and the Western powers agreed that the Papuans should be given an independent state, but due to global considerations, mainly the Kennedy administration’s concern to keep Indonesia on their side of the Cold War, the United States pressured the Dutch to sacrifice Papua’s independence and transfer the territory to Indonesia.”

The Free Papua Movement was formed in December of 1963. Those who continue to seek independence have declared December the 1st as ‘Independence Day’. Ongoing violence has seen an estimated 100,000 indigenous Papuans lose their lives. Many others have crossed the border into PNG to escape the violence and seek refuge.

A medal for Maria

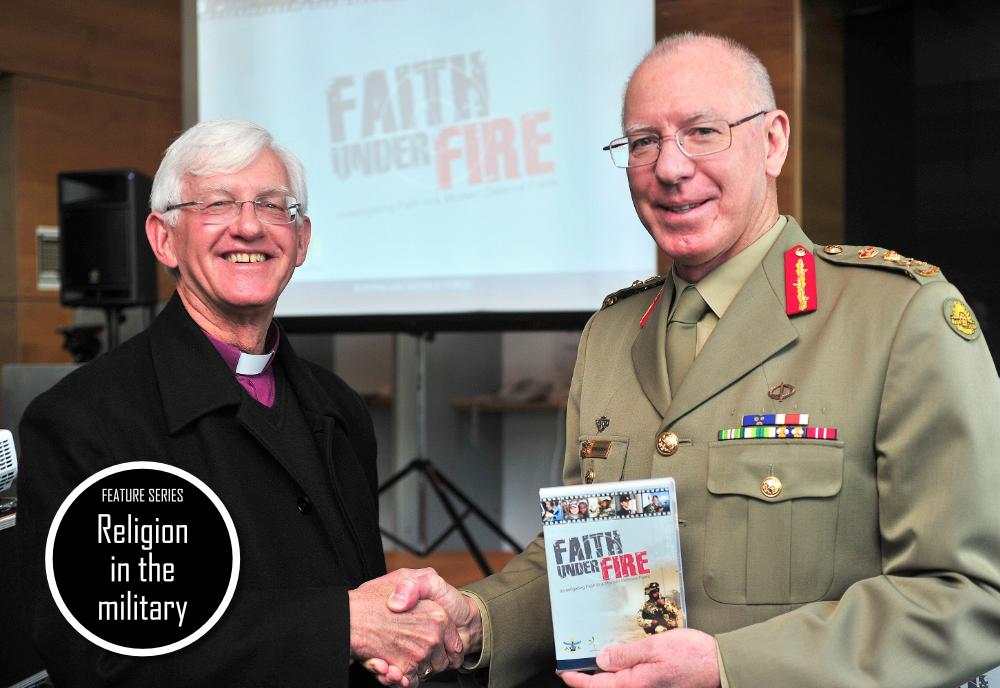

In 1995, long after I had left the army, the government introduced some new service medals. One is for those who served in what are called “prescribed non-warlike operations” between 1945 and 1975. This is the Australian Service Medal 1945-1975.

The medal applies to 14 operations outside of Australia, with each having a clasp that’s affixed to the ribbon. Those operations are: Berlin, Far East Strategic Reserve, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Kashmir, Korea. Middle East, PNG, South East Asia, Special Ops, South West Pacific, Thailand and West New Guinea.

The Australian War Memorial has a list of ‘Deaths as a result of service with Australian units’. From 1860 to the present, there have been 102,888 deaths. The list includes 49 deaths of those who served in one of the 14 ‘non-warlike operations’. You didn’t need to serve in a shooting war to have died in the service of our country.

Some military museums are general in nature, some relate to specific operations and some relate to specific units. There is no plaque that relates to the 14 ‘non-warlike operations’, which cost 49 lives.

The Curator of Honour Rolls at the Australian War Memorial sent me a picture of a bronze panel which lists names of those who died in the ‘non-warlike operations’. The name of the soldier who died at Vanimo doesn’t appear on the roll. The Curator stated that: “…individuals currently commemorated on the Roll of Honour for Operational Service are those whose names have come to the Memorial’s attention since 2007, however there may be possibly eligible individuals whose names we are not aware of. The individual you have referred to is one of these cases.”

Some military museums are general in nature, some relate to specific operations and some relate to specific units. There is no plaque that relates to the 14 ‘non-warlike operations’, which cost 49 lives.

I served alongside soldiers who had been to Vietnam and even the Korean war. One veteran of the Korean war served with the 3rd battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment, which received the United States Presidential Unit Citation for “…the outstanding bravery demonstrated by the men…” during the battle of Kapyong in April of 1951. Yet, the fact remains that those on the frontline couldn’t do what they do without the service of the ordinary soldiers in supporting roles.

I have been eligible for the Australian Defence Medal and the Australian Service Medal 1945-1975 since their inception in 1995. But it was only a few years ago that I made an application. This was Maria’s idea. She wanted to wear them along with her father’s Dutch Second World War Mobilization Cross.

For me, a hero is an individual who was in a certain place at a certain time and had a disposition to act a certain way. All our attributes and achievements are a product of our biological inheritance and the circumstances that allow for the expression of that inheritance. Nurture always exists within the context of nature. To take personal credit for your attributes and achievements is irrational and unscientific. Given our individual human uniqueness, evidenced by our DNA profiles, to do your best is to be the best in the world in your category of one.

This article was originally published in the June 2021 edition (vol. 121) of Australian Rationalist

Photo by Bob Brewer on Unsplash