NOTE: This article discusses suicide. If you are a veteran or someone in need of support, you can find appropriate support services here on the website of the Royal Commission into Defence & Veteran Suicide.

I served in the Australian Army for close to thirty years. I joined at the age of 17 years and went to Duntroon. My family was proud, middle-class and conservative. We had a good, loving home.

My family didn’t really understand, though, that I had to leave to escape stifling religion. The excellent public school education they had given me had also made me realise that religion was irrational and evil.

I read Nahum 1:2 about the age of nine and got fobbed off when I asked questions. I was there well before Dawkins. The Bible was the only thing I was allowed to read in church. Give a bored kid with a high reading level nothing to read and what do you expect!

My service after graduation included all the usual regimental and staff appoints a middling officer could expect. I was never going to be a general, nor did I want to be; but I was trusted enough to serve as a commanding officer of a regiment.

General George S. Patton is often quoted as saying, “Troops are like spaghetti – you have to pull them, not push them.” It is what makes being an Army officer challenging and rewarding. If you master that skill of pulling the troops, you will see it in the way those assigned to your command work. Sometimes I got it wrong. Mostly, I think, I got it right.

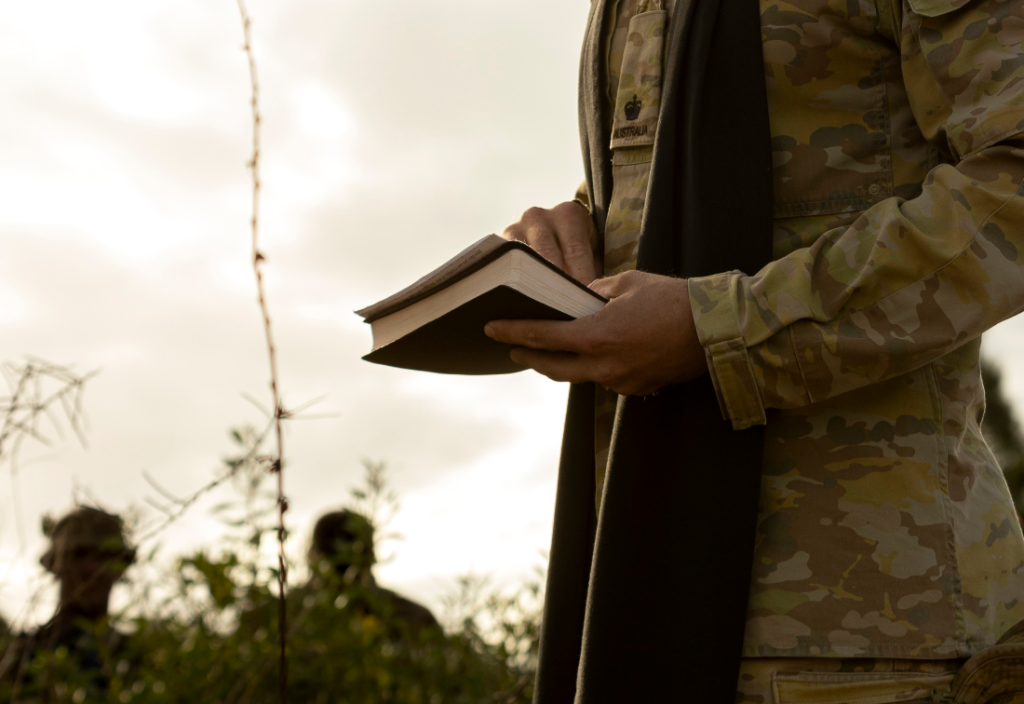

My chaplain never ran a church service. To allow him to do so would have been exclusionary to those of other faiths or no faith. In the same way I could not exclude a soldier from any activity because of a belief or orientation, I could not allow a Christian service in a secular regiment.

The wars of this century have been fought with an undertone of sectarianism. Sometimes subtle as it was in Timor Leste; other times manifest, such as against ISIS. Those conflicts and my involvement in them have left me with physical, neurological and psychological injury. Most of them are invisible. I am only given away by the leg braces I now wear and the magnificent assistance dog forever by my side.

I live with constant suicidal ideation. My daily flashbacks are in colour, vivid and angry. I smell and taste blood, sweat, burning pork and diesel. I chain smoke to stop the taste and smell. Sleep is absent. I am seeing a psychologist weekly, a psychiatrist and a GP fortnightly.

Admission to a veteran’s mental health facility for a few weeks at a time is frequent. Most of the veterans at the facility express no religious belief or are Buddhist. About 20-30 per cent of the staff are Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist or Sikh. They are wonderful.

I was in the facility on 11 November last year. The facility’s chaplain held a service that day. Few inpatients attended. No staff from the other faith groups were present. It was representative of white Christianity from the start. It was a very good service from that perspective. The chaplain, a veteran himself, did a great job.

I wanted to remember my previous generations who served in both world wars. But, once again, there was the hypocritical prayer for peace to Jesus who proclaimed, “Think not that I am come to send peace on earth: I came not to send peace, but a sword” (Mathew 10:34).

Such Christian acts of worship bring harm to those already suffering from the moral injuries of war.

I have spoken at length with the nurses and treating psychiatrists about this – asking for the Christian iconography to be removed. I have also submitted formal feedback asking for action to be taken. Nothing has been done.

I am now at the stage where I have to raise the issue through a formal complaint with my state’s mental health care network. It shouldn’t have to come to this.

The debate over religious services on Anzac Day isn’t just about sectarianism and secularism. It is about the harm that religious services do to veterans like me who have experienced the evil religion does.

Published 3 April 2025.

If you wish to republish this original article, please attribute to Rationale. Click here to find out more about republishing under Creative Commons.

Photo by Department of Defence (Commonwealth of Australia).