Few constitutional principles are more familiar to the average American than the separation of church and state. According to the Pew Research Center, 73 per cent of adults agree that religion should be kept separate from government policies.

To be sure, support varies by political or religious affiliation – with Democrats supporting the principle in much higher numbers – and depending on the specific issue, such as prayer in public schools or displays of the Ten Commandments monuments. Yet only 19 per cent of Americans say the United States should abandon the principle of church-state separation.

That said, criticism appears to be on the rise, particularly among political and religious conservatives. And such criticism comes from the top.

Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson remarked in 2023 that:

“The separation of church and state is a misnomer … it comes from a phrase that was in a letter that [Thomas] Jefferson wrote. It’s not in the Constitution. And what he was explaining is they did not want the government to encroach upon the church — not that they didn’t want principles of faith to have influence on our public life.”

As a scholar of American legal and religious history, I have written extensively about the development of religious freedom in the US, and the origins of the separation of church and state.

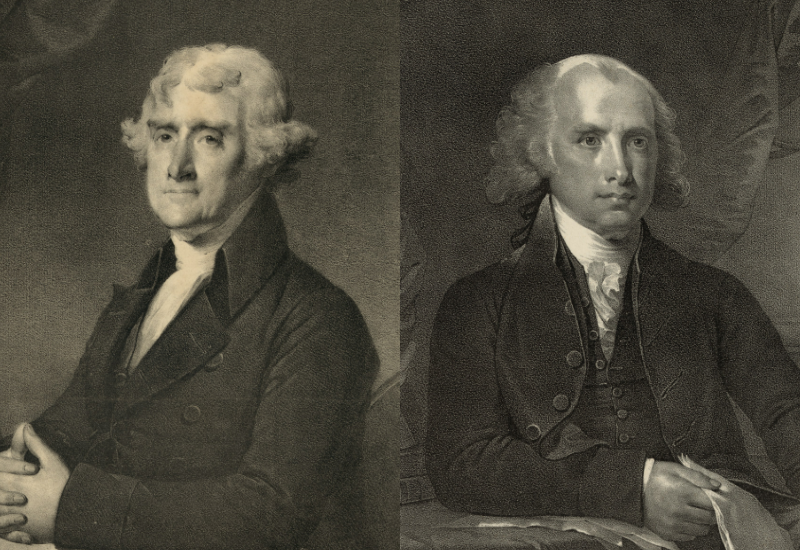

Two of the Founding Fathers shaped American views on these topics more than any other: Jefferson and James Madison. Yet their views have also become lightning rods for controversy as the “wall” between church and state comes under scrutiny.

My forthcoming book, The Grand Collaboration, seeks to answer several questions: What was Jefferson’s and Madison’s understanding of religious freedom? And why were they so deeply committed to that principle?

Jefferson wrote the Virginia Bill for Religious Freedom in 1777, the most comprehensive declaration of religious freedom at the time. The bill guaranteed freedom of conscience, protected religious assemblies from government oversight, prohibited government funding of religious institutions and boldly declared that religious opinions were outside the authority of civil officials.

Several years later, Madison guided these ideals into law. His Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, a protest against a proposal to support Christian teachers with tax money, affirmed the values of church-state separation and religious equality. He helped defeat the proposal – and set the stage for Virginia to adopt Jefferson’s bill.

As president, Jefferson went on to pen a letter to a Baptist association in Connecticut where he immortalized the phrase “a wall of separation between church and state.”

The Bill of Rights contains two clauses about religion, both in the First Amendment: that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” What qualifies as “establishment of religion,” however, is open to debate.

In 1947, the US Supreme Court embraced church-state separation as the guiding principle for interpreting the religion clauses, relying extensively on the two Virginians’ writings and actions. As Justice Hugo Black wrote:

“In the words of Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation between Church and State.’”

The duo’s documents served as the authority for the legal principle of church-state separation, and for more than five decades their bona fides remained unquestioned in the law.

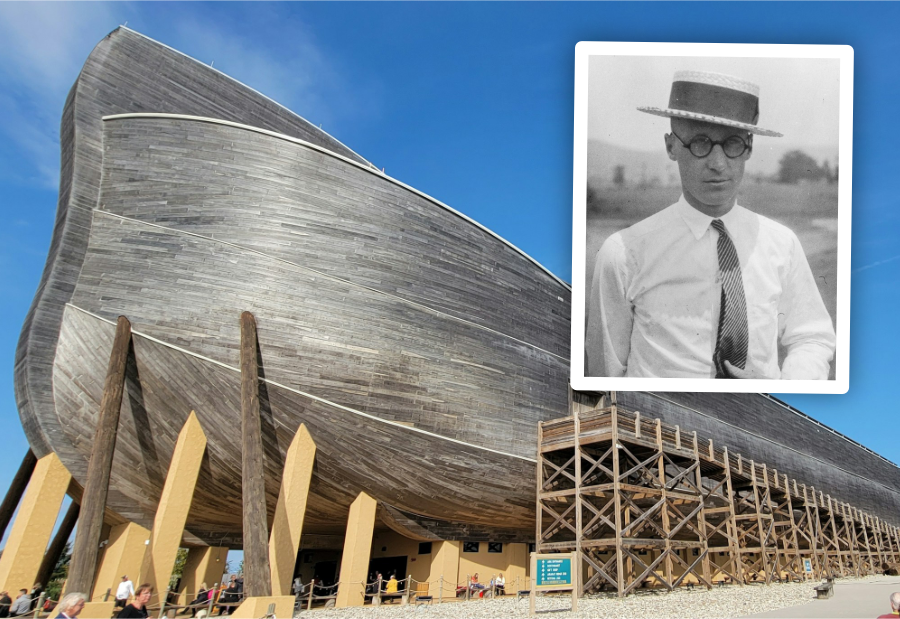

Criticism of church-state separation intensified in the 1980s. As the religious right grew into a political force, commentators argued that the concept was anti-religious and did not represent the prevailing views about church and state during the founders’ time.

In recent decades, such arguments have attracted politicians and jurists, including members of the Supreme Court. Justice Clarence Thomas has written that the court’s earlier separationist interpretations of the Constitution “sometimes bordered on religious hostility”. Legal scholar Philip Hamburger has declared that “the constitutional authority for separation is without historical foundation” and “should at best be viewed with suspicion”.

Several recent Supreme Court decisions have rejected a separationist approach to church-state matters. For example, the conservative majority has allowed taxpayer dollars to be used at religious schools, the display of religious symbols on government property, and religious expression by public school employees.

In a 2022 dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor bemoaned that the court has turned the separation of church and state from a “constitutional commitment” to a “constitutional violation”.

The justices’ earlier reliance on Jefferson and Madison has borne the brunt of criticism that their views on church-state matters did not represent their peers, or that neither man was in favor of separation as he has been portrayed.

To better understand Jefferson’s and Madison’s beliefs, I examined many of the 2,300 letters between the two on Founders Online, a National Archives website. I also looked at correspondence with other acquaintances.

Both founders had deistic leanings, meaning they believed in a supreme being, but thought science and reason were the best paths to understanding religion. They were only nominally observant Christians, but more protected from religious intolerance than other “dissenters” due to their high social standing and affiliation with the Anglican Church.

All the more striking, then, that they worked throughout their lives to advance religious freedom.

Religious matters were never far from their minds. For instance, in Madison and Jefferson’s exchanges discussing the need for a bill of rights, freedom of conscience was invariably at the top of the list. Both were convinced that government should avoid supporting religion, even if no particular religion was given preference. They also insisted that people should have broad religious freedoms.

These views were clearly on the vanguard, but other religious rationalists and religious dissenters also advocated a comprehensive understanding of religious freedom.

Both men were committed to advancing religious freedom because they saw it as deeply entwined with freedom of inquiry and conscience. “Reason and free enquiry are the only effectual agents against error,” Jefferson wrote in 1784. Allowing people to investigate ideas freely “will support the true religion,” because “Truth can stand by itself”.

Similarly, Madison declared “the freedom of conscience to be a natural and absolute right”.

In their view, free inquiry was the fount of other rights. Religious freedom, for example, was a subset of freedom of conscience. And a healthy separation of church and state was key to ensuring those freedoms.

The letters reveal the extent to which Jefferson and Madison complemented and reinforced each other’s attitudes toward church and state. They also reveal the close intellectual and emotional affection that each man held for the other, and how much each man valued the other’s support.

In their final exchanges before Jefferson’s death on 4 July 1826, he implored Madison:

“To myself, you have been a pillar of support thro’ life. Take care of me when dead, and be assured that I shall leave with you my last affections.”

Madison responded with similar affection:

“You cannot look back to the long period of our private friendship & political harmony, with more affecting recollections than I do.”

Jefferson’s and Madison’s half-century of collaboration on behalf of religious freedom and equality is an important chapter in the nation’s founding history. I believe its legacy should be remembered and celebrated, not discarded.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Images: Library of Congress / Library of Congress